Marco Arment is the developer behind Instapaper, the devilishly useful time-shifting tool for reading. Just as a DVR allows you to watch Mad Men when it’s convenient for you — say, at 6:45 p.m. Thursday instead of 10 p.m. Eastern on Sunday — Instapaper lets you read long-form prose when you’ve got the time and attention to devote to it. Come across a long interesting magazine piece in your daily web travels, but don’t have time to read it just then? Click Instapaper’s “Read Later” bookmarklet and it’ll be pulled into your iPhone (or Kindle or whatever) for offline reading when you’re on a plane or train. I love it.

But rather than just praise a terrific app, I want to point out a couple tweets of Marco’s that might tell us a little something about the paywalls we’ll see news organizations start erecting in greater quantities soon. Arment recently decided to start offering a paid model for Instapaper’s web service. He calls it an Instapaper Subscription, and it’s $3 for three months. What do you get for your $3? Arment is blunt:

Right now? Almost nothing, except knowing that you are supporting the Instapaper service’s operation and future feature development…

Some future features may be Subscriber-only, but please don’t buy a Subscription solely because you expect these exclusive features to be mind-blowing. They might be, depending on how easily your mind is blown, but I’d feel better if you bought the Subscription because you wanted to support Instapaper.

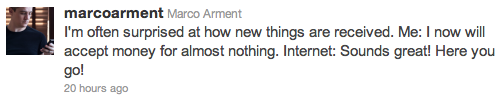

Now that’s a soft sell — pay me three bucks and I’ll give you roughly zero in return! But reaction to the move around the web has been overwhelmingly positive, as this tweet indicates:

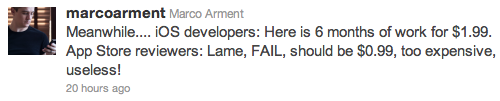

He contrasts that with the often vociferous reaction some have to iPhone app developers who dare to charge a couple bucks for their work, rather than the expected price of $0:

An app is not a breaking story, and software is not journalism — but I think there’s some wisdom for news organizations here.

— The economic value of your work is determined by the market, not wishes and hopes. Is it fair, in a cosmic sense, that people are willing to pay $3 for three months of “almost nothing” when it comes to Instapaper, but not pay $2 for an iPhone app that took an enormous amount of hard work? No! But prices aren’t set by principles of fairness: They’re set by the market. These are economic decisions, not emotional ones.

Is it fair that I’ll pay $20 a month for an email newsletter about book publishing, which is produced by a handful of people, but wouldn’t pay $20 a month for online access to The Boston Globe, which is the collective work of hundreds of talented journalists? No! But fairness doesn’t much enter into it. I’ve heard lots of journalists use words like “deserve” and “earned” when they describe why they want the paywalls to go up around their work. But the goal is to maximize the economic return on journalists’ work, not to act out of anger.

— Requiring payment isn’t always more fruitful than encouraging it. Imagine for a moment that instead of asking for subscriptions, Arment had put up an iron-clad, Times-UK-style paywall — pay $1 a month or else no more Instapaper for you. In that case, there’d probably be some users who’d pay up who wouldn’t with Arment’s soft sell.

But Instapaper has a classic competitive substitute good: a very similar service called Read It Later. Is Read It Later as good as Instapaper? I don’t think so — but it’s plenty good enough for the vast majority of people. A hard Instapaper paywall might raise revenue, but at the cost of driving away a huge chunk of customers off whom money might be made some other way — through advertising, say, or by being converted later to paying customers, or simply by promoting the app to their friends.

Most news is the very definition of a substitutable good. If CNN.com put up a paywall, MSNBC.com would be there waiting to collect the free traffic. Ditto The Washington Post and The New York Times. Most online news consumers aren’t looking for specific stories; they’re looking for something to occupy their time for a few minutes that makes them feel better informed. There will always be lots of free alternatives that can fill those duties. That’s why, while I’m happy to see news organizations experimenting with pay models, I’ve also been happy to see them setting reasonable expectations for the outcome and thinking a lot about how to maximize both revenue and audience.

— Love and affection drives money. Why are people giving Marco Arment money for nothing? Because they love it. Check out these tweets:

In the online world of free, people need a damned good reason to fork over their money. It had better solve a problem, bring consistent delight, or otherwise earn devotion. A small but devoted audience can be worth more than a big, uncommitted one. How many people love their local newspaper?