There was a lot of buzz on Twitter yesterday about Paul Farhi’s piece in The Washington Post on checkbook journalism — in particular the way a mishmash of websites, tabloids, and TV news operations put money in the hands of the people they want to interview. (With TV, the money-moving is a little less direct, usually filtered through payments for photos or videos.)

There was a lot of buzz on Twitter yesterday about Paul Farhi’s piece in The Washington Post on checkbook journalism — in particular the way a mishmash of websites, tabloids, and TV news operations put money in the hands of the people they want to interview. (With TV, the money-moving is a little less direct, usually filtered through payments for photos or videos.)

But, just for a moment, let’s set aside the traditional moral issues journalists have with paying sources. (Just for a moment!) Does paying sources make business sense? Financially speaking, the justification given for paying sources is to generate stories that generate an audience — with the hope that the audience can then be monetized. Does it work?

There’s not nearly enough data to draw any real conclusions, but let’s try a little thought experiment with the (rough) data points we do have, because I think it might provide some insight into other means of paying for content. Nick Denton, the head man at Gawker Media and the chief new-media proponent of paying sources, provides some helpful financial context:

With the ability to determine instantly how much traffic an online story is generating, Gawker’s Denton has the pay scale almost down to a science: “Our rule of thumb,” he writes, “is $10 per thousand new visitors,” or $10,000 per million.

What strikes me about those numbers is how low they are. $10K for a million new visitors? There aren’t very many websites out there that wouldn’t consider that an extremely good deal.

Let’s compare Denton’s Ratio to the numbers generated by another money-for-audience scheme in use on the Internet: online advertising. After all, lots of ads are sold using roughly the same language Denton uses: the M in CPM stands for thousand. Except it’s cost per thousand impressions (a.k.a. pageviews), not cost per thousand new visitors, which would be much more valuable. What Denton’s talking about is more like CPC — cost per click, which sells at a much higher rate. (Those new visitors aren’t just looking at an ad for a story; they’re actually reading it, or at least on the web page.) Except it’s even more valuable than that, since there’s no guarantee that the person clicking a CPC ad is actually a “new” visitor. Let’s call what Denton’s talking about CPMNV: cost per thousand new visitors.

CPC rates vary wildly. When I did a little experiment last year running Google AdWords ads for the Lab, I ended up paying 63 cents per click. I ran a similar experiment a few months later with Facebook ads for the Lab, and the rate ended up being 26 cents per click.

What Denton is getting for his $10 CPMNV is one cent per click, one cent per new visitor. It’s just that the click isn’t coming from the most traditional attention-generating tool, an ad — it’s coming from a friend’s tweet, or a blogger’s link, or a mention on ESPN.com that sends someone to Google to search “Brett Favre Jenn Sterger.”

And that $10 CPMNV that Denton’s willing to pay is actually less than the return he gets for at least some of his source-paid stories. Take the four Gawker Media pieces that the Post story talks about: the original photo of singer Faith Hill from a Redbook cover, to show how doctored the image was for publication; photos and a narrative from a man who hooked up with Senate candidate Christine O’Donnell; the “lost” early version of the iPhone 4 found in a California bar; and voice mails and pictures that allegedly show quarterback Brett Favre flirting with a woman named Jenn Sterger, who is not his wife. Gawker publishes its pageview data alongside each post, so we can start to judge whether Denton’s deals made financial sense. (Again, we’re talking financial sense here, not ethical sense, which is a different question.)

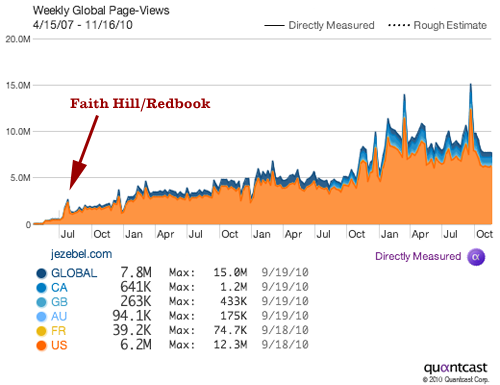

Faith Hill Redbook cover: 1.46 million pageviews on the main story, and about 730,000 pageviews on a number of quick folos in the days after posting. Total: around 2.2 million pageviews, not to mention an ongoing Jezebel franchise. Payment: $10,000.

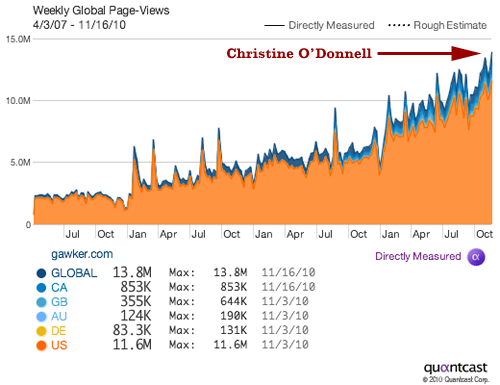

Christine O’Donnell hookup: 1.26 million pageviews on the main story, 617,000 on the accompanying photo page, 203,000 on O’Donnell’s response to the piece, 274,000 on Gawker’s defense of the piece. Total: around 2.35 million pageviews. Payment: $4,000.

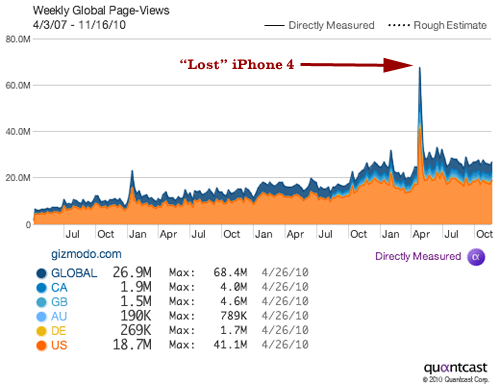

“Lost” iPhone: 13.05 million pageviews on the original story; 6.1 million pageviews on a series of folos. Total: around 19.15 million pageviews. Payment: $5,000.

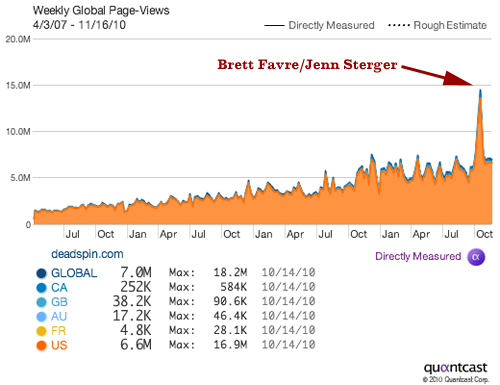

Brett Favre/Jenn Sterger: 1.73 million pageviews on the first story, 4.82 million on the big reveal, 3.99 million pageviews on a long line of folos. Total: around 10.54 million pageviews. Payment: $12,000.

Let’s say, as a working assumption, that half of all these pageviews came from people new to Gawker Media, people brought in by the stories in question. (That’s just a guess, and I suspect it’s a low one — I’d bet it’s something more like 70-80 percent. But let’s be conservative.)

Expected under the Denton formula:

Faith Hill: 1 million new visitors

O’Donnell: 400,000 new visitors

iPhone: 500,000 new visitors

Favre: 1.2 million new visitorsGuesstimated real numbers:

Faith Hill: 1.1 million new visitors

O’Donnell: 1.17 million new visitors

iPhone: 9.56 million new visitors

Favre: 5.27 million new visitors

Again, these are all ham-fisted estimates, but they seem to indicate at least three of the four stories significantly overperformed Denton’s Ratio.

The primary revenue input for Gawker is advertising. They don’t publish a rate card any more, but the last version I could find had most of their ad slots listed at a $10 CPM. Who knows what they’re actually selling at — ad slots get discounted or go unsold all the time, many pages have multiple ads, and lots of online ads get sold on the basis of metrics other than CPM. But with one $10 CPM ad per pageview, the 2.2 million pageviews on the Faith Hill story would drum up $22,000 in ad revenue. (Again, total guesstimate — Denton’s mileage will vary.)

Aside: Denton has said that these paid-for stories are “always money-losers,” and it’s true that pictures of Brett Favre’s manhood can be difficult to sell ads next to. Most (but not all) of those 10.54 million Brett Favre pageviews were served without ads on them. But that has more to do with, er, private parts than the model of paying sources.

But even setting aside the immediate advertising revenue — the most difficult task facing any website is getting noticed. Assuming there are lots of people who would enjoy reading Website X, the question becomes how those people will ever hear of Website X. Having ESPN talk about a Deadspin story during Sportscenter is one way. Having that Redbook cover emailed around to endless lists of friends is another. Gawker wants to create loyal readers, but you can only do that from the raw material of casual readers. Some fraction of each new flood of visitors will, ideally, see they like the place and want to stick around.

Denton publishes up-to-date traffic stats for his sites, and here’s what the four in question look like:

It’s impossible to draw any iron-clad conclusions from these squiggles, but in the case of Jezebel and Deadspin, the initial spike in traffic appears to have been followed by a new, higher plateau of traffic. (The same seems true, but to a lesser extent, for Gizmodo — perhaps in part because it was already much more prominent within the gadget-loving community when the story broke than, for example, 2007-era Jezebel or 2010-era Deadspin were within their target audiences. With Gawker, the O’Donnell story is too recent to see any real trends, and in any event, the impact will probably be lost within the remarkable overall traffic gains the site has seen.)

I’ve purposefully set aside the (very real!) ethics issue here because, when looked at strictly from a business perspective, paying sources can be a marker for paying for content more generally. From Denton’s perspective, there isn’t much difference between paying a source $10,000 for a story and paying a reporter $10,000 for a story. They’re both cost outputs to be balanced against revenue inputs. No matter what one thinks of, say, Demand Media, the way they judge content’s value — how much money can I make off this piece? — isn’t going away.

Let’s put it another way. Let’s say a freelance reporter has written a blockbuster piece, one she’s confident will generate huge traffic numbers. She shops it around to Gawker and says it’ll cost them $10,000 to publish it. That’s a lot of money for an online story, and Denton would probably do some mental calculations: How much attention will this story get? How many new visitors will it bring to the site? What’s it worth? I’m sure there are some stories where the financial return isn’t the top factor — stories an editor just really loves and wants to publish. But just as the Internet has turned advertising into an engine for instantaneous price matching and shopping into an engine for instantaneous price comparison, it breaks down at least some of the financial barrier between journalist-as-cost and source-as-cost.

And that’s why, even beyond the very real ethical issues, it’s worth crunching the numbers on paying sources. Because in the event that Denton’s Ratio spreads and $10 CPMNV becomes a going rate for journalists as well as sources, that means for a writer to “deserve” a $50,000 salary, he’d have to generate 5 million new visitors a year. Five million is a lot of new visitors.

There’s one other line Denton had in the WaPo piece that stood out to me:

“I’m content for the old journalists not to pay for information. It keeps the price down,” Denton writes in an exchange of electronic messages. “So I’m a big supporter of that journalistic commandment – as it applies to other organizations.”

When we think of the effects of new price competition online, we often think of it driving prices down. When there are only a few people competing for an advertising dollar, they can charge higher rates; when there are lots of new competitors in the market, prices go down. But Denton’s basically arguing the equally logical flipside: I can afford to pay so little because there aren’t enough other news orgs competing for what sources have to offer. Let’s hope we don’t get to that same point with journalists.