No old-world icon is safe. Just in recent weeks, both Kodak and Sears have percolated back into the news, offering headline writers a dilemma borrowed from the classic Saturday Night Live Weekend Update line, “Generalíssimo Francisco Franco is still dead.”

How long have these companies been dying? Yes, it was a surprise sometime a long time ago, that digital media was challenging Kodak and that Walmart, Target, Kohl’s, and later Amazon were making life difficult for one of America’s retailing pioneers.

Ask an American in 1990 if they could imagine a world without Kodak. Or a shopper of a world without Sears. Now, in 2012, it’s a lot easier to imagine. These are companies ebbing away, drip by agonizing drip. Which reminds us, of course, of the newspaper industry, and the question still on some lips: Can you imagine a world without newspapers? Now two years into the tablet, it’s much more easily imaginable. I always laugh when asked the question, “Will newspapers exist in 2015 or 2020?” Papyrus is a durable medium. It’s just that digital is rapidly replacing print, and in the process rapidly restructuring the nature of news ownership, news creation, news employment, and more. We’ll have some kind of print for the rest of our lives, but it will be the sidecar to the revving engine of digital news and information, as more and more publishers call it quits on print.

We like to think of change in the world as an on/off switch. This….or that. In fact, the world changes both in an instant and agonizingly slowly.

Let’s call the slow disappearance of familiar brands the newsonomics of the long goodbye. Take companies that have huge imprints in our culture and habits — and cashflows to match — and their disappearance from our lives can seem like it is moving in glacial digital time. But that disappearance is no less real. It is a fact of the news landscape that newspapers, and to some extent consumer print magazines, will disappear over time. We can take bets how much more quickly they’ll continue to vanish. By continue, I mean that data shows 44 percent less newsprint usage (and about 75-80 percent of all newsprint usage is attributed to newspapers) over the past four years, according to The Reel Time Report. (And for more on the industry-leading Michigan Meltdown, check out Alan Mutter’s column at E&P.)

So we can see this goodbye is both real and long. At some point, though, you see this message (on one medium or another), “Kinograph to cease production of silent films,” as borrowed from the neo-silent film The Artist. (Perhaps someday we’ll be talking about “neo-print”?)

Let’s ask a couple of questions about the relationship of Kodak, Sears, and newspapers. How do their revenue slides compare? What lessons apply across the three?

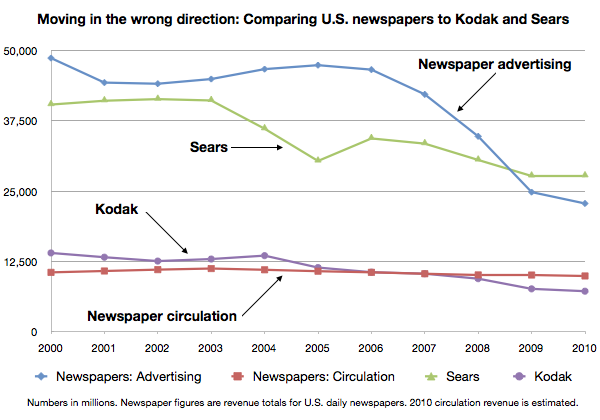

On revenues, take a look at the chart below. I’m tracking revenues from Kodak, Sears, and all U.S. dailies through 2010 — with final 2011 data not yet in, though the year wasn’t kind to any of the three.

What stands out most prominently is that U.S. newspapers’ ad revenue decline is worse, percentage wise, than either Kodak’s or Sears’. Yes, although Kodak and Sears are now poster children of legacy businesses gone wrong, newspapers — as counted through their main revenue source — are doing worse.

Ad revenue is down 53 percent over the period shown, while Kodak’s overall revenues are down 49 percent. Sears’ overall revenues (I removed Kmart revenues, which became part of the Sears Holding Company in a 2005 merger) are down 31 percent over the same period.

The savings grace for newspapers has been circulation revenue, down a relatively low 6 percent in the last decade. Circulation has continued to plummet, but continuing price increases have moderated the revenue losses. Circulation revenue now makes up about 30 percent of all U.S. daily newspaper revenue, so it’s significant — but not enough to stabilize companies reeling from ad revenue loss.

If you combine ad and circulation revenue, over the decade, newspapers have lost 45 percent of the two tentpoles of their business overall, four points less than Kodak.

Share prices will tell us a similar story, as investors — slow to the understanding of the long goodbye — head for the exits.

What are the threads among our three cases? Digital news pioneer Steve Yelvington shared a similar thought about Kodak/newspapers relationship, this week, noting that “brands decay” and “disruption doesn’t happen just once,” among other lessons.

Let’s extend the metaphor. Remember those “Kodak Photo Spots,” where tourists were encouraged to stand and take the exact same picture that tens of thousands had taken before them? Let’s put the newspaper owner — or buyer, given that there’s been a spate of recent purchases — on that spot, and see what they can see about this landscape.

The viewing is hugely important. Why? While we may say newspapers are dying, we can say long live the news. Those owning — or buying into or creating news franchises — do still have time to pivot and learn from failure. History is not fate; this Kodak/Sears history is simply a big cautionary tale from which to learn, a slomo Kodak moment.

With that in mind, let me suggest five points of learning deeply applicable to news management decisions of 2012:

One newer victim of the old mindset may give us pause: Best Buy. Best Buy built expensive and dominating superstores, eating alive the CompUSAs and Circuit Cities. Now Amazon and a hundred websites have made buying a 62-inch TV cheaper and as easy to deliver to your house as a sweater. Faced with disappointing financial results in an otherwise booming holiday season, Best Buy CEO Brian Dunn, like his Kodak, Sears, and newspaper counterparts before him, is left to sputter: “This misguided perspective [that electronics buying is moving profoundly online] is especially troubling for me, because it blatantly and recklessly ignores overwhelming evidence to the contrary.” His irritation is understandable — but history is proving increasingly hostile to those failing to adapt fast enough.

Kodak camera photo by Kevin Stanchfield used under a Creative Commons license.