Your Uncle Larry from Pensacola, the one who still has a faded “Impeach Clinton” bumper sticker on his pickup, wants you to know something: Barack Hussein Obama, that socialist we just re-elected, is abolishing the national Christmas tree this year. This isn’t a rumor; this is a fact. And now you have two choices: delete this email or forward it to everyone you know.

The Internet’s oldest social network still hums with chain emails like this. FactCheck.org calls it a zombie rumor, returning from the dead every year since Obama took office. The president is a constant target of the email rumor mill: He is a radical Muslim; he canceled the National Day of Prayer; he gave away part of Alaska to Russia; he lets his dog fly on its own jet.

We just went through a highly fact-checked election, but it’s unclear what the final score was between truth and fiction. One reason why myths persist is that fact-checking is often out-of-reach at the moment it would be most useful — like the moment where you open your inbox. Forwarding an email is a lot easier than hunting for evidence. So Matt Stempeck, a graduate student at the MIT Media Lab, is tackling the problem closer to its source.

Stempeck and developers Justin Nowell, Evan Moore, and David Kim have written a Gmail plugin called LazyTruth that quietly scans your email for chain letters, urban legends, and phishing scams. When you open a forwarded email, an “Ask LazyTruth” button invites you to investigate. The software checks the email against data pulled from PolitiFact and FactCheck.org, and, if needed, offers a correction and a link to find out more.

Once a user clears the first (and only) hurdle — installing it as a Chrome extension — the plugin does all the work. The gap between the consumption of misinformation and the correction is reduced to nearly zero. (When it works.)

“The Washington Post has a great fact-checking column, but it’s for people who read the Post once a week, dive into a fact-check for 500 words,” Stempeck said. “There’s a much larger audience of people who would want the summary of that in one sentence if they get the email with that lie or mistruth in it. Basically, as far as journalism goes, it’s seeing if we can take the homework and the research and the knowledge that goes into an individual article and bring it out into the world and give it to people when they really want and need it.”

Take FactCheck’s fact-check of a chain letter claiming the president secretly criminalized protests against him. The deconstruction of that claim is breathtaking in precision and rigor, but it’s unlikely to reach the people who ought to read it. The people who trust the chain letter in the first place probably want to believe the claims are true. This is the essence of truthiness: “the quality of preferring concepts or facts one wishes to be true, rather than concepts or facts known to be true.”

Which gets to another problem: Are the people who install LazyTruth the people who really need it? And shouldn’t LazyTruth be an AOL plugin instead of a Chrome extension?

Stempeck said he expects LazyTruth users to be a mostly self-selecting, technically inclined audience. And that does not defeat the purpose, he said. He may not be able to reach Uncle Larry, but maybe he can empower Uncle Larry’s relatives with facts to help bring him back down to earth.

“I’ve received emails from friends of my family saying that climate change has nothing to do with mankind,” Stempeck told me. “Off the bat, I know that that’s not true, but I’m not always going to take the time out of my day to go summarize the recent science on it in two quick paragraphs for my friends. If I had a tool that surfaced that for me, I might be more likely to respond with that information.”

Stempeck wants to see if LazyTruth inspires people to push back in any number. Would 1 percent of users pushing back make a measurable impact on the spread of those emails?

If it sounds similar to Dan Schultz’s Truth Goggles, the work we wrote about last November and again in May, it is. The two have worked together at the Media Lab’s Center for Civic Media. Stempeck hopes to make use of Schultz’s work with natural-language processing to identify variations of common phrases in chain letters. For now, LazyTruth can only match exact strings against Stempeck’s huge and growing database of chain letters and their variations.

Chain letters have a lot of common features: They tend to be laced with exclamation points. They tend to be anonymous. They tend to be conservative. They tend to be riddled with spelling errors. And they always insist this is not a hoax!!!!!!!!!

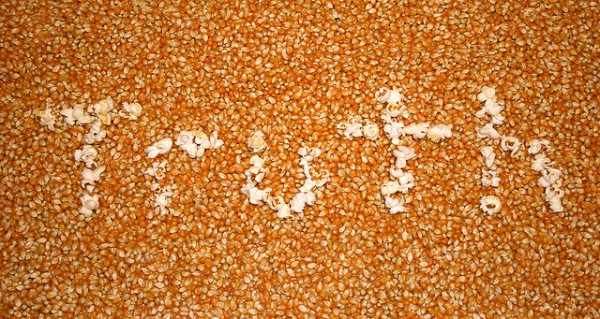

To help debunk — and not reinforce — email myths, Stempeck has studied The Debunking Handbook from Australian researchers John Cook and Stephan Lewandowsky. “If your content can be expressed visually,” the guide advises, “always opt for a graphic in your debunking.” So for the zombie Christmas tree hoax (Stempeck’s favorite), LazyTruth offers a photograph of First Lady Michelle Obama and Malia Obama in front of the horse-drawn wagon conveying the national Christmas tree, the sign reading “White House Christmas Tree 2010.”

Other tips from the handbook:

Next Stempeck wants to mine the data to learn more about the content of chain letters, how they mutate, who the primary actors are.

“Some of these emails, they’ll get updated for different nations and context,” Stempeck said. “I would also love to do some network analysis of how these things spread, how many people need to forward them for them to stay alive, and how many people actually forward them versus people that don’t? Is it like spam, where .001 percent is enough to keep it alive?”

Please forward this story to 10 people in the next five minutes.

Photo by Dave used under a Creative Commons license.