Imagine coming up with 25 distinctly different headlines for each and every story you file. Insane, right?

Maybe, but it’s a key part of the strategy at Upworthy, the still-pretty-newish site devoted to sharing meaningful content and getting other people to spread it.

Before settling on “What Are Selena Gomez And Justin Bieber Doing In The House Of Representatives?” the team at Upworthy drew up more than two dozen alternate headlines for this video:

Here’s how they brainstormed (bold indicates Upworthy staff favorites):

2. Can You Spot The Celebrity Immigrant?

3. Racial Profiling Celebrities: Arizona’s ‘Show Me Your Papers’ Law Fails This Test

4. NO, REALLY: Senator Asks The House To Spot The Immigrant

5. Who Is A Prouder American: Selena Gomez or Justin Beiber?

6. Senators Play “Pick Out The Immigrant” In The House of Representatives

7. Do You Think The Founding Fathers Imagined A Future Where Senators Played “Pick Out The Immigrant” In The House Of Representatives?

8. Would The Founding Fathers Be Proud Of The Fact That Our Political System Has Come To This?

9. What Are Selena Gomez And Justin Bieber Doing In The House Of Representatives?

10. Watch Your Senators Play “Pick Out The Immigrant” In The House Of Representatives

11. How About We Teach Arizona’s Cops Not To Be Racist Instead Of Wasting Tax Dollars On Photos Of Selena Gomez And Justin Bieber?

12. Why Isn’t Justin Bieber Proud To Be American?

13. Don’t You Just Love When Senators Get So Angry Their Sarcasm Shows?

14. What’s Wrong With Arizona’s ‘Show Me Your Papers’ Law? Rep. Gutierrez Explains…With Sarcasm!

15. Don’t You Just Love When C-SPAN Gets Sarcastic?

16. C-SPAN Channels TMZ As Senator Uses Selena Gomez And Justin Bieber To Make A Point About Racism

17. C-SPAN: Sarcastic Senator Steals The Show

18. C-SPAN Is Usually Pretty Boring. This Is Not.

19. Sweeps Week C-SPAN: Featuring Selena Gomez, Justin Beiber, and Sarcasm!

20. What Do Geraldo Rivera, Selena Gomez, Jeremy Lin, And Sonia Sotomayor Have In Common?

21. Sarcastic Senator Steals The Show With Sonia Sotomayor And Selena Gomez

22. Sarcastic Senator Steals The Show

23. If You’re A Senator And You Want My Support, Be Sarcastic On C-SPAN.

24. Spot The Celebrity Immigrant And You Could Be An Arizona Police Officer!

25. Cool Senator Or The COOLEST Senator?

(And yes, for the record, Luis Gutierrez serves in the House of Representatives, not the Senate. Give them a break — it’s brainstorming!)

Why spend so much time tweaking a headline? It’s all part of the Upworthy mission to make meaningful stories go viral.

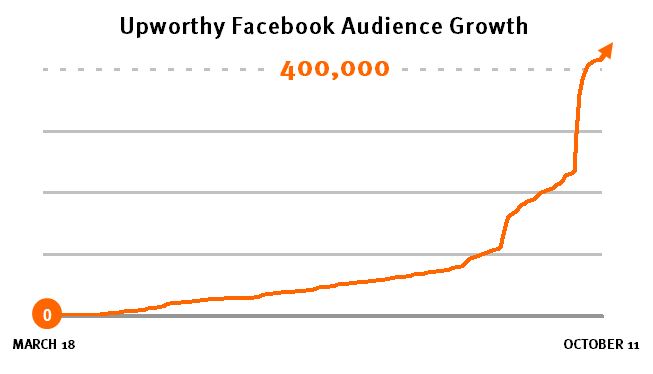

So far, it’s working. The site expects to notch 7 million uniques in October. It already has more than 400,000 Facebook fans, all with a fledgling staff of about a dozen people, and in just seven months since launching at the end of March.

“We really didn’t know if this would work at all,” cofounder Eli Pariser — perhaps best known for his work at Moveon.org and his book The Filter Bubble — told me. “We’ve had lots of meetings with people who have been in the media industry for a long time who were like, ‘Yeah, good luck.’ Everybody’s trying to somehow cover the broccoli with chocolate sauce and make it go down easier, and you end up with something that tastes horrible. It’s been so awesome to see the hunger that people actually have for content that does have meaning. That’s what gets me so excited: proving the thesis that people don’t just want fluff stories. People do actually want to be engaged, and treated like adults, and thinking about interesting and thoughtful stuff.”

Take a look at this growth:

Those graphs would seem to validate Upworthy’s assumptions about how virality works — that online packaging and distribution are as important as having quality content in the first place.

That might sound painfully obvious: What good is stellar reporting if you can’t get it in front of people’s eyeballs? But many news organizations still appear to treat social packaging and distribution as an afterthought. You spend days reporting and writing a story, minutes coming up with the headline, and seconds tweeting it. At Upworthy, there are three equally-important priorities for each “nugget” of content — many nuggets are video clips — to use the in-house terminology:

Let’s break it down some more. What kind of content matters? That is, what does it take for something to be deemed Upworthy?

“I think about that in a couple ways,” Upworthy cofounder Peter Koechley told me. “One question that we ask our curators to ask themselves is, ‘If 1 million people saw this, would it make the world a better place?’ which allows for a lot of interpretation. Curators could disagree on that.” That’s a good thing: If curators have to make the case for a video clip internally, they’re forced to be thoughtful and persuasive about why it’s worth sharing.

While Upworthy explicitly seeks content that will elicit an emotional reaction from those who encounter it, something that’s straight-up heartwarming or entertaining might not make the cut. That’s why President Barack Obama doing his best Al Green didn’t fly. (Pariser explained: “I got a kick out of that video, but is it meaningful? Not really. It’s kind of presidential celebrity.”)

For a video to be quintessentially Upworthy, it has to resonate broadly and deeply. Take, for example, this video clip of a Wisconsin news anchor addressing the viewer who called her fat.

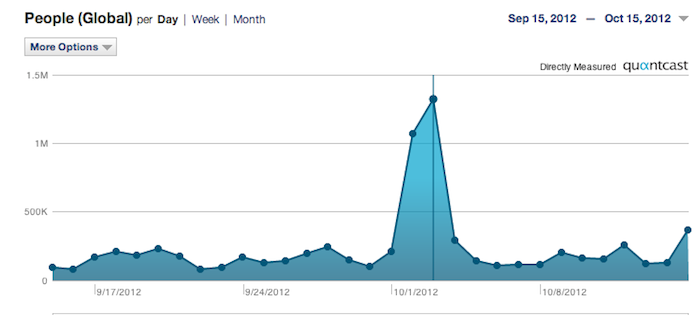

Just check out the traffic spike Upworthy got once it posted that video:

Ultimately, Upworthy drove about a quarter of the hits that this video got — “significantly more than Mashable, Reddit, People.com, BuzzFeed, and other sites known for their traffic-driving prowess,” according to Upworthy’s Maegan Carberry. Check out this graph by Stephan Daniel, who posted the video first and shared these analytics with Upworthy:

Whereas BuzzFeed’s founder has talked about the bored-at-work audience as one of the site’s key networks, Pariser sees Upworthy’s crowd as a distinct yet similarly social audience.

“We see ourselves as serving a somewhat different but equally powerful network, which is like a searching-for-meaning network,” Pariser said. “People who want to be part of something that feels like it has a purpose. And that’s actually a big ecosystem of people and of content. It’s also content that doesn’t have a traditional audience or place to go. So partly what we want to build is to strengthen or amplify that network.”

Upworthy takes some stances on broad issues — equality is good, bullying is bad — but tries to stay away from the nitty-gritty of partisan politics. Striking that balance isn’t always easy. One example is this video of a bold speech by Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard:

Gillard’s speech was political. But especially to a global audience, there was something about it that felt bigger than, say, Gillard’s political record against same-sex marriage. That something bigger was what Upworthy wanted to share. Here’s how Upworthy community manager Kaye Toal explained it to me in an email:

Ultimately, we think that sexism — especially such blatant sexism as this — is one of those things that most people agree is decidedly gross.

There’s also an aspect of a shared human experience here that’s really appealing — she is at once eloquent and speaking to something that many women understand, and many people who have women that they love in their lives understand. It was a moment of a shared catharsis that really hit that human narrative nerve.

People were sharing because they were impressed, or because they agreed, or because they identified and felt vindicated, but they were learning in the process — this comment thread was actually one of my favorites to moderate that week, because people were so interested in discussing the nuance of the issues with one another.

The team at Upworthy is obsessed with sharing content that roils emotions, and equally fixated on the data it collects along the way. Hong Qu, who is in charge of user experience for Upworthy, says part of his job is approaching virality as a science.

“Not every story will have the same exact resonance with your audience,” Qu told me. “If you do see one that’s an outlier that’s taking off, you shouldn’t just be happy and look at it and say, ‘Congratulations.’ You’re missing the opportunity to tweet it to so many people — to send it to all the people you have. There’s a theory in psychology about why people try new things and adopt new behavior. When they see three of their trusted friends recommend something to them, that’s the effect you want to induce artificially. You’re manufacturing virality.”

For Qu, who says his graduate degree in social psychology guides much of his thinking about Upworthy, considering why people share content is as important as making content worth sharing in the first place.

“We care about shares because that’s how we acquire new customers,” Qu said. “You have to attract people to walk in the door. For a storefront, it’s very easy. What’s the equivalent of that in digital space? We have a pretty sophisticated algorithm, like a radar detection system for how shares are doing, how a particular article drives more customers.”

Instead of looking at audience the way a television broadcaster might describe reaching 10 million homes, Upworthy looks at its audience through what it calls “generational analysis.” Generation one is the group of people who get content directly from Upworthy, generation two refers to people who get content from the first generation, and on and on and on. Upworthy says it has tracked generational shares into the twenties.

And while Qu says “no one else is really even close” to such sophistication in measuring how audiences interact with content and one another, the big question that’s still without a precise answer is why something goes viral at all.

“Sometimes it’s a mystery to me why something gets so many generations,” Qu said. “We can tell how many people are sharing it, but we can’t really tell the sentiment, which side they stand on, what they say about the story itself.” (To help figure out how people feel when they decide to share, Upworthy is working on a feature that will let audiences vote — not unlike Rappler’s Mood Meter and other newsy mood experiments.)

Qu says he has a long wishlist of features to develop. He wants to make an “Upworthy” button that might go next to the Facebook “like” button. He likes the idea of real-time, public virality statistics, so viewers can see if something they’re watching is going viral as they’re encountering it — the idea being that people like to feel as though they’re part of something. Qu admits that it can be scary to think about building something for the site that might take even six months — from a development standpoint, rapid iterative development is key to staying ahead of the curve.

But Upworthy is not beholden to the time constraints that most newsrooms face. (And remember, Upworthy isn’t a newsroom, as its staffers repeatedly emphasized.) When it comes to content, Upworthy won’t hesitate to share a video that’s years old if it’s the best way to capture the zeitgeist.

“We do try to hit timely news cycles,” Toal said. “The Todd Akin thing, we were all over that. But you can pull up older content to talk about those same things, the same way you would in a conversation with a friend. If news organizations are about keeping you up to date, Upworthy is more about reminding you what matters, and introducing you to other things that matter.”

This mentality fits with the site’s revenue model. Upworthy gets funding from sponsor partners who pay for affiliation to certain content — and, in turn, access to a certain kind of audience. An environmental group might want to give people the opportunity to sign up for its newsletter after an environmentally-themed video. A group that aims to increase voter turnout might sponsor a video related to that issue. The approach to sponsorship is another way that Upworthy is BuzzFeed-esque, as sponsors are deliberately paired with content.

The difference between BuzzFeed and Upworthy, as Toal describes it: BuzzFeed might post eight pictures of Lady Gaga dressed in meat, whereas Upworthy would post eight ways being dressed in meat affects the poor. If the big question is what makes something go viral, the even bigger question is how do meaningful viral videos translate into real-world action?

“It’s hard to measure,” Toal says. “It’s not like we can go to each of our Facebook fans and ask, ‘What have you done today?’ We’re thinking about that more. But the other thing is, I think the unvoiced part of that question is whether or not sharing something on Facebook is inherently less valuable than going door-to-door. I’m not convinced that it is. Either way, you’re educating.”

So while Upworthy is decidedly not a news organization — although hasn’t ruled out a future that includes original reporting; note today’s post featuring “Upworthy’s first-ever real live actual poll of swing-state voters” — the site clearly shares some of journalism’s core values. As cofounder Pariser puts it, they’re also some of the loftiest.

“To put it in sort of hopelessly, naively idealistic newsroom terms, we do believe you need an informed citizenry to make decisions in a democracy,” Pariser said. “And if you do that well, then good things will come. That’s sort of the article of faith for us. If you can actually bring something like childhood poverty in America to people’s attention, people want to do something about it. The reasons those problems don’t get fixed is mostly that they don’t get noticed, because Kim Kardashian is getting noticed instead.”