Clippy (real name: Clippit) was an innovation for Microsoft; the idea that a piece of software could predict what you were working on based on what you typed was startlingly new to the average consumer. But Clippy was also annoying — very annoying. He popped up all the time, unbidden, and was both rarely helpful and hard to get rid of. Over time, Clippy became a meme synonymous with obnoxious, digital interruptions.

The backlash against the chirpy, distracting animation was widespread and eviscerating. Clippy was killed in 2001; Microsoft actually launched an anti-Clippy campaign to market Office XP in 2002. In 2010, Time named Clippy to a “50 Worst Inventions” list. The backlash against the animated algorithm was so intense, in fact, that it inspired its own backlash; in 2012, developers at Smore built a Javascript Clippy so that the bouncy paperclip could live on in perpetuity.

The backlash against the chirpy, distracting animation was widespread and eviscerating. Clippy was killed in 2001; Microsoft actually launched an anti-Clippy campaign to market Office XP in 2002. In 2010, Time named Clippy to a “50 Worst Inventions” list. The backlash against the animated algorithm was so intense, in fact, that it inspired its own backlash; in 2012, developers at Smore built a Javascript Clippy so that the bouncy paperclip could live on in perpetuity.

Clippy made sense in theory, but in practice, the office assistant made users feel intruded upon. Today, the typical consumer is more accustomed to the feeling of being watched by technology. We know that Google reads our email to predict flight times, and we know Facebook tracks our searches to sell to advertisers. But just because customers have come to expect it doesn’t mean they like it. The question for tech companies is a tricky one — just how far into their personal and professional lives will users allow software to go?

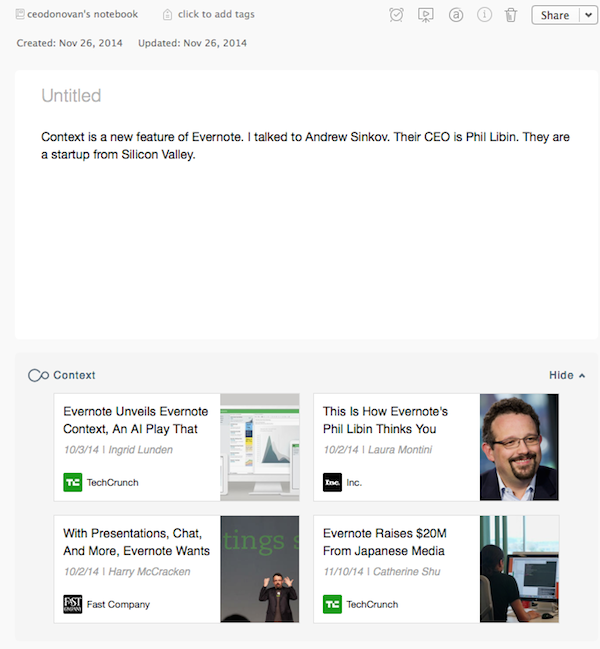

That question is one that Evernote, the note-taking-turned-workspace app, has been struggling with lately. Earlier this fall, Evernote released Context, a new product that aims to seamlessly integrate the research process into a user’s workflow. As you type a note, Evernote not only searches for and provides relevant material from your own and colleague’s work, but also from third-party news organizations.

“Think of the note area in Evernote like a big search box,” says Andrew Sinkov, Evernote’s vice president of marketing. “If you write one sentence and that one sentence contains the word Evernote, we may surface an article about Evernote. But if you write two paragraphs and now you’re talking about some specific feature like Evernote Web Clipper, now we have a lot more information to go on catered to the specific search that you happen to be doing. If TechCrunch has written an article about our Safari Web Clipper in the last few months, we will surface that.”

To build Context, Evernote needed a way to match what a user was working on with relevant content. To do that, they hired a team of augmented intelligence researchers, who created an algorithm that is constantly trying to match keywords from what users are typing to related terms in outside material.

To get this material, Evernote had to locate willing media partners who would give the company access to some or all of the news organization’s archives. Their first partner was The Wall Street Journal, which makes the the most recent 90 days of its archives available and searchable via Context. Next month Dow Jones will add in its Factiva databases. In the future, the program could also surface videos and images in addition to text articles.

The partnership makes sense for Evernote because the majority of its users are “information workers” — small business owners, entrepreneurs — with an interest in reading business journalism. The Wall Street Journal, meanwhile, gets access to elite users — only Evernote Premium and Business members get Context — and the chance to expand brand recognition outside of the traditional newspaper subscriber base.

“What we’re predominantly focused on is giving our existing subscribers a better experience,” says Edward Roussel, head of product for Dow Jones. “Point number two, we’re looking to recruit new subscribers.”

The Journal launched a loyalty in September called WSJ+. Perks of premium membership include subscriptions to things like Evernote Business, one reason the partnership makes sense for the paper. The other reason is growth, especially international growth.

Only a quarter of Evernote’s users — 100 million people have signed up for or downloaded the app — are in North America. The rest are mostly in Asia, especially China, and South America. For the Journal, that means Evernote is a platform for continuing to extend their brand globally, something Roussel told Digiday he’s explicitly working to accomplish via partnerships with companies like Evernote.

Evernote is also interested in its foreign customers: The most recent addition to the list of Context media partners — which currently includes TechCrunch, Fast Company, Inc., Pando Daily, Crunchbase, and LinkedIn — is the Nikkei, an English-language Japanese business newspaper. (The Nikkei is part of the large media company Nikkei, which invested in Evernote to the tune of $20 million.) As Evernote’s presence in Japan grows, the platform could become an inroad for the Journal to build a stronger presence there as well. For example, though for now Evernote only surfaces English-language Wall Street Journal content, down the line Japanese users could be served local, Japanese-language Wall Street Journal content.

“Evernote is very strong in Japan, we’re strong in Japan — we have a large number of readers and a strong subscription base. It’s the kind of experiment that we’re interested in, other things that we can do that are specific to a particular demographic,” says Roussel.

For publishers, Context is a unique, if niche, way to get their content in front of engaged, professional eyeballs. What Evernote hopes to offer those users attached to those eyeballs is a productive, predictive way to work the likes of which they’ve never experienced before.

The problem is not all Evernote Premium and Evernote Business users who have experienced Context see it as a feature.

Not sure about this new Evernote stuff. Why would I want these generic results? And they can't be turned off? pic.twitter.com/a2XdXH22or

— Federico Viticci (@viticci) October 31, 2014

@viticci damn. Context is the stupidest thing @evernote has done in years.

— Rui Carmo (@rcarmo) October 31, 2014

@viticci Actually, this stuff is a real reason that will keep me from buying Evernote Business again.

— Lukas (@Blubser) October 31, 2014

The discomfort with and dislike of Context was so great at launch, in fact, that users soon started sharing methods for disabling it.

The negative reaction to Context springs from two places. The first is that the stories’ square-tiled appearance in the sidebar makes them resemble ads, which makes Premium users especially feel like their private workspace is being encroached on.

@viticci Thank goodness it can be disabled, but disheartening that @evernote chooses to spend time on this sort of thing. Ads in my notes?

— Jeff Donnici (@jdonnici) November 2, 2014

@viticci I hate this new feature – feels like advertising inside my private documents. Feels wrong. @evernotehelps are you listening?

— Samuel Jay (@RealSamuelJay) November 2, 2014

Sinkov says the assumption by Context users that recommended links were ads surprised the people who built the product. “Context sits at the very bottom of your note. It’s not at the side, it’s not at the top, there aren’t any popups, it’s not flashing,” he says. “What is that reaction? Why do you so viscerally hate a rectangle that shows up beneath your note at a distance from your cursor that is pretty significant?”

Despite the effort that went into designing a product that wouldn’t annoy or disrupt users, that apparently doesn’t change the fact that when some users see a logo in the margins of their screen, they read it as an ad. Both the Journal and Evernote said that no money exchanged hands in forming the Context partnership, but that fact may not be enough in the face of engrained assumptions about how websites treat their readers.

“Unfortunately, ads take so many forms these days there’s no way to design a space that could not be perceived as an ad,” says Sinkov. “That’s the challenge we have.”

But Evernote Context has another challenge beyond repairing a spammy-looking interface. Though Sinkov says the third-party publishers have no access to Evernote data, that’s not necessarily clear to the user. The idea that Evernote has access to the content of all notes, both personal and professional, and is using that data to power an algorithm without asking the user to opt-in is, to some, worrisome. The fear that those notes — which could contain, for example, proprietary business information — are somehow being made available to unknown journalistic entities could be seen as downright disturbing.

@viticci I want out of the whole algorithm, to be honest.

— Nate Boateng (@nateboateng) October 31, 2014

Sinkov says Evernote is aware of these concerns, and is working to address them with users. “We have these three laws of data protection that we take very seriously, about privacy and data ownership and data portability,” he says. For example, though it would be theoretically very useful for Evernote to use the content of notes to learn more about the demographics of its user base — where they work, how old they are, where they live — they don’t.

Going forward, Sinkov says Evernote needs to do a better job of publicizing the steps the company takes to protect users. He believes that if people better understood how Context works — that the data flows only one way and that there’s no money involved — they would be more open to the benefits of the product. Without that information being made explicit, users often assume the worst of tech companies; with recent headlines in mind, it’s not hard to see why.

“We’ve been beaten down in some ways by expectations that ‘the company is going to sell my data, and I’m not going to know about it, and it’s going to be bad.’ That’s why these unfortunate reactions happen,” Sinkov says.

There are, of course, Evernote users who enjoy using Context, which makes sense. The idea of having links to background information made available automatically as I write sounds convenient and useful — no more opening a new tab and searching for the CEO’s name or the source’s appropriate title or the date of the original launch. Frictionless delivery of the facts I need to do my work without having to ask for it sounds, to me, like the future. But it takes a significant amount of private information to power tools like that, and it’s often unclear which companies are reliable enough to be trusted with that information. As our digital world becomes increasingly circumscribed by the machines that watch us as we work and play, we will be faced with more frequent decisions about who and what else we want to see in those spaces.

“The algorithms we have running are intended to do one thing. If there’s a fatigue that says ‘I don’t want algorithms,’ that’s unfortunate,” Sinkov says. “There are good algorithms, and there are less good algorithms. If we wanted to stay in a world where it’s literally your head to your fingers to a keyboard to a screen, we’re there. That’s already the world we live in. What’s next?”