Now Atavist, the Brooklyn-based publishing platform and digital magazine that once counted IAC, Andreessen Horowitz, and Google’s Eric Schmidt among its backers, is facing similar struggles. After failing to raise new funding, the startup has laid off half its staff and is looking for ways to cut costs and stick around.

“We could go around chasing money, and potentially go down in flames chasing money all the way to the end,” CEO Evan Ratliff told me. “Or we could figure out a way to make what we’re doing sustainable. Unfortunately, that involved letting some really wonderful people go.”

The most recent round of layoffs included employees in business development, engagement, design, magazine production, and software. Another designer was laid off earlier in November. Developers Gray Beltran and Jeff Sisson and director of developer experience Derrick Schultz left independently for jobs at The New York Times within the past three months.

Remaining employees include Ratliff, CTO Jefferson Rabb, magazine executive editor Katia Bachko, director of reader experience Thomas Rhiel, and office manager Kathleen Ross, Rather than hiring new full-time employees, the company will continue to rely on contractors (something it’s already done for several functions) and outsource some tasks like server maintenance.

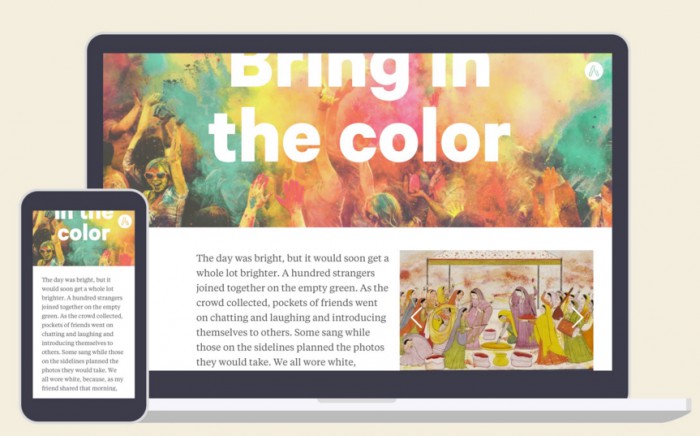

The Atavist’s primary revenue driver is its publishing platform, which aims to help creators write, design, and publish interactive stories for mobile and desktop without knowing any code. The platform (once called Creatavist but now simply known as Atavist) has 65,000 users. A reported 400 of those are paying between between $8 a month and thousands of dollars a year; bigger-name clients include Mental Floss, California Sunday Magazine, and The Daily Dot, while organizations like Frontline and Harvard University have also published stories.The user base has grown by more than 15 percent in each of the past three months. “We have a clear path to profitability, but we needed more time,” Ratliff said.

Best months for user growth at @atavist:

1) November 2015

2) October 2015

3) September 2015

4) August 2015

— Nicholas Thompson (@nxthompson) November 28, 2015

The Atavist Magazine, which has served as both a home to original longform reporting and an example of the publishing platform’s capabilities, will continue to publish one story a month. Magazine stories have been nominated for National Magazine Awards and an Emmy, and “Love and Ruin,” by James Verini, won a National Magazine Award for feature writing this year, the first time a story from a digital outlet has done so.

Yet former employees said the company’s direction had felt uncertain for awhile. “It felt like the company was a thought experiment and not really a company,” one told me. “The pace was kind of glacial. There wasn’t a lot of hustle.”

Atavist, founded in 2011 by Ratliff, Rabb, and now-New Yorker editor Nicholas Thompson, has undergone a couple of shifts in direction over the past few years. It started out licensing its technology to Pearson, in a relationship that later ended when the Pearson executive running the initiative left.

Then, in 2012, producer Scott Rudin, IAC chairman Barry Diller, and publishing executive Frances Coady formed a partnership (initially known as Brightline, later called Atavist Books) to publish ebooks in collaboration with Atavist. IAC provided capital to build out Brightline “in addition to making investments in Atavist,” the Times reported.

“There is a possibility here that if we start with a blank piece of paper that you could hit the opportunity that exists in the book business now,” Diller told the Times.

Atavist Books published its first title, a novella by bestselling author Karen Russell, in March 2014, and in the following months published another five ebooks. But in October 2014, IAC decided to shut the initiative down in a decision that appears largely based on IAC’s misjudgment. “We have identified that the market for highly innovative enhanced full-length literary ebooks still heavily relies on a print component and has yet to emerge,” a spokesperson told Publishers Lunch.

Following Atavist Books’ shuttering, IAC participated in another $2 million debt/funding round.

Further fundraising efforts, however, have been unsuccessful. Ratliff and Rabb were forthcoming with employees about the money’s burn rate, and it “probably would’ve been easy to see that the company would hit emergency mode around now, failing further funding,” a former employee told me.

“It seemed like it was not the right time for us to raise money,” Ratliff said.

On the platform side — which is now seen as the main opportunity for growth from the company — Atavist originally put a lot of development resources into native apps, before announcing in September of this year that it would discontinue them in favor of the web.

“The idea that a publication is going to obtain readers en masse through a native app, or that it provides an experience more valuable than the mobile web,” Ratliff and Rabb wrote, “has turned in the last five years from a hope to a fantasy.”

Former employees described the decision as one that was made too late. “The app product hadn’t seen love or attention in at least a year,” one former employee said. The apps also had not had a dedicated developer for several months; one former employee described them as “a dilapidated, ownerless project.”

“They could have made that decision a long time ago and gotten a more radical press bump, but at the time it was announced, the writing was on the wall, at least internally,” another former employee said.

Atavist is also confronting circumstances outside its control. One seemingly obvious competitor is Medium, which is increasingly working with outside organizations on custom publications. Atavist has attempted to differentiate itself through software, a focus on publishers rather than individual writers, and the ability to sell stories. (“Our focus is storytelling, design packaging and creating deep, engaging content, not being a social network,” former head of business development Saft told Digiday in October.)VCs were also arguably more aggressive about funding writing- and reading-related startups in recent years than they are today — something that becomes all the more clear when you look at the fates of Oyster, Byliner, Readmill, and others in the space.

In addition, longform storytelling is no longer seen as the potential industry savior it was a couple of years ago, though The Atavist has undoubtedly had a large impact on the space. And publishers are increasingly embracing platforms like Facebook’s Instant Articles and Snapchat Discover as places to distribute their stories. If the tradeoff for millions of eyeballs on your content is the loss of personalized design features and the unique look that Atavist has specialized in, well, so be it. (In that end-of-native-apps announcement, Ratliff and Rabb did hold out the possibility that “in the future our stories may be available directly on the social networks now pulling in articles to load faster in their environments, like Facebook Instant or Apple News.”)

If the delay in killing off its apps was somewhat emblematic of an overall sense of stasis and malaise at Atavist, it does also suggest the company’s ability to adapt to changing circumstances, albeit belatedly. “They figure out ways to make things work, and that seems somewhat unique within the tech and media landscape,” a former employee told me. “But it certainly made it challenging, being an employee there. You want to feel like there’s direction. Some kind of thing being worked toward. And that was not forthcoming.”

“This is still a founder-controlled company,” Ratliff said. “We’re not in a situation we didn’t have any choices. We can still say we started this company because we wanted to tell certain types of stories and do a certain type of design. Both of those things actually work, to an incredible extent. We want to find a way to keep them going for a long time. Unfortunately, maybe, it wasn’t the way we were doing it before.”

A previous version of this article listed laid-off employees by name.