Long before City Room, Snow Fall, NYT Now, or any other of The New York Times’ lauded digital efforts, there was NYTimes.com, which 20 years ago today — on January 22, 1996 — began “publishing daily on the World Wide Web…offering readers around the world immediate access to most of the daily newspaper’s contents.”

The Times reported on the event, of course: “The electronic newspaper (address: http:/www.nytimes.com) is part of a strategy to extend the readership of The Times and to create opportunities for the company in the electronic media industry.” The story ran on Page D7.

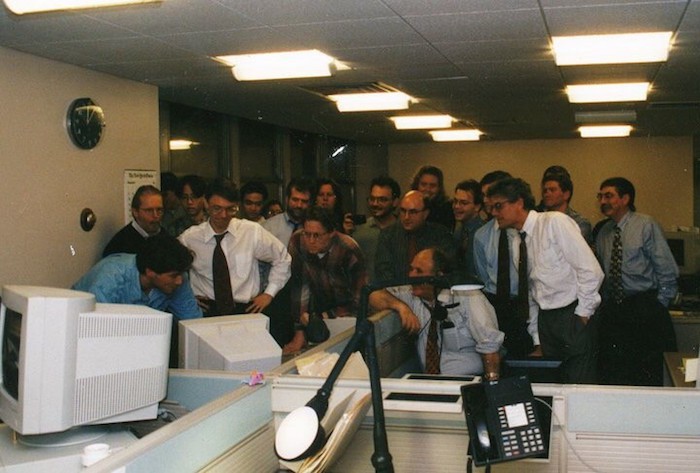

Happy 20th birthday to https://t.co/sYpRHsjbKc which went live on this day in 1996. https://t.co/yU78iM8u6r pic.twitter.com/GFGFGbUdsI

— NYT Archives (@NYTArchives) January 22, 2016

(The eagle-eyed will notice that the online version of the story gets the address slightly wrong, with only one slash after the “http:” rather than two. Today’s web browsers can deal with the omission; those of 1996 couldn’t. The print version — which is where people would have been reading it, naturally — got it right.)

The Times’ had begun publishing on AOL in 1994. In 1995, the Times created The New York Times Electronic Media Company to develop the paper’s digital presence, and that fall it launched the first beta of the Times’ website.

Martin Nisenholtz was president of the Times Electronic Media Company and joined the company in 1995 to launch the website. In a 2013 interview for the Riptide project, Nisenholtz — who came to the Times from an advertising and interactive media background — explained how the paper approached the new website (see this video starting around 9:30 in):

My thinking was, The New York Times should maybe approach the web, in some ways, the way Yahoo did. Yahoo was a kind of directory, and I thought, “Well, jeez, the Times could do, in essence, what Yahoo was doing. It could find the best stuff for people.” The journalism of The Times, probably, was not — at that point, in any event — very interesting on a PC. It was just very, very clunky. But I realized very quickly that was just not going to happen.

What The Times wanted, for good reason in some ways, was to publish the journalism of The New York Times on the web. In fact, that’s what I think, probably, 99 percent of the people who would use The New York Times on the web would expect from it.

Now, of all the things, of all the decisions that have been made, I think that one is the most seminal. The idea to publish what was, in essence, the newspaper instead of going in a different direction at the outset.

I think that, certainly, publishing the newspaper on the web is what was expected. It’s what the consumer expected. It’s what was logical. It was low risk, in many respects. It didn’t cost very much because we already had the content. It made a world of sense.

But, in some ways, some fundamental ways, it kept the Times from truly being a great innovator, because it didn’t allow for something startlingly new. [laughs]

At launch, the Times’ website was free for users in the United States, but the paper decided to charge readers who accessed the site from abroad. For $1.95 a pop, users could also download stories to their computers and the site also offered “a customized clipping service” that let users set up email alerts by topic.

From a business perspective, Nisenholtz said, the Times’ focus was squarely on online advertising, so the paper wanted to build as large an audience as it could on its website, and after about 18 months it decided to stop charging readers outside of the United States for access to the site.

Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger, speaking at a 1995 Nieman Foundation conference on public interest journalism in the “On-Line Era” called the paper’s digital efforts an “experiment.”We got, I want to say, about 3,600 subscribers. One of the things I like to say is we ended the experiment on Bastille Day, and that day, I believe it was in 1998, we got more registered users in about an hour than we had subscribers in the last 18 months.

The fact is that, at that time, in a general news context, given the quality of the product that we were building in a narrowband context, very crude technology, we absolutely, I think, made the right decision to build the audience because, as I think we’ll get to later, we’ll see that a lot of the economics of going pay have to do with conversion rates off of your loyal base, the people who are coming to you every day.

“We don’t know where this is going. In the end, it’s going to have to pay for itself,” Sulzberger said. “We do know that. In the end, it’s going to have to pay for itself. And there’s not a lot of ways to make money.”

Sulzberger went on to say that he expected it would take some time for the Times to figure out how to make money online, but ultimately he thought it would be feasible:

I don’t need to make money this year, and I don’t need to make money next year. And I’d like to lose a little less money the year after that…But at some point, and some point not very far down the line, we’re going to have to start seeing a financial return. And I don’t think that’s going to be as difficult as we think it is today, because I think the ethos and ethics of the web are changing.

I guess I’m betting on that, aren’t I? Am I wrong?

He wasn’t wrong, but it took the Times a while to get there.

The Times’ initial assumption was that it would be able to support its web operations by selling display and classified ads on its website. An onslaught of competition from online companies hampered the Times’ (and other newspapers’) advertising business both in print and online, upending the news industry’s business model.

Though the Times quickly abandoned its first attempt to charge for its journalism online — and had only middling success with its mid-2000s effort TimesSelect, killing it after two years — it eventually came back to the strategy for good in 2011 when it launched its metered paywall. Print advertising revenue is still critical, making up 73 percent of the Times’ total ad revenue in the third quarter last year, but the paper is looking increasingly to digital subscriptions for revenue growth.

Last year, the Times said it had signed up 1 million paying digital subscribers, and in October it said it aimed to double its digital revenue to $800 million by 2020. One of the keys to that initiative will be digital subscriptions; just today Mashable reported that the Times is experimenting with cheaper subscriptions for iPhone users. It’s also trying to reach new audiences by optimizing its reporting for different mediums, especially on mobile, while also offering higher quality advertising products. In addition, the Times is attempting to reach more subscribers internationally by adding foreign-language editions.Though the Times’ digital output has obviously grown immensely since 1996, it’s still experimenting with how it will continue to report and tell stories online — and it can all be traced back to that day 20 years ago when the Times debuted on the World Wide Web.

“At the time, nobody really could know ultimately how important this was,” Nisenholtz said in an interview in December with the Times’ corporate site. “We all had a sense that something important was happening, but at the time there were actually very few users. So it was a bet on people getting online and buying more PCs.”