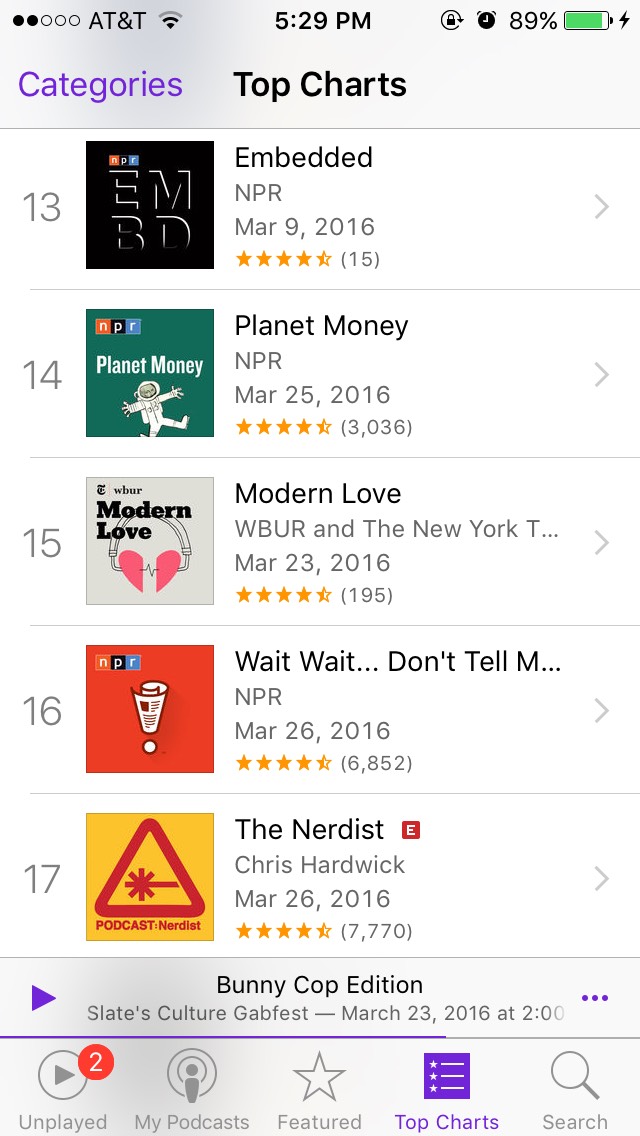

“Embedded” in the context of journalism refers to war correspondents attached to a military unit. NPR’s newest podcast, launching Thursday, borrows the term but expands it. Embedded, in its first 10-episode season, follows All Things Considered cohost Kelly McEvers and other NPR reporters as they embed with a range of people, places, and situations — from spending nearly a full week inside a house in Indiana with people addicted to the opiate painkiller Opana to following Skid Row residents and police officers on patrol.

“How many times have you seen something in the news and thought to yourself, I want to know more?” said McEvers, who was sent to Baghdad in 2010 and covered the unrest in the Middle East from the Arab Spring to the beginnings of the Syrian conflict, until she returned to the U.S. in 2013. Last September, she and Ari Shapiro were added as cohosts of NPR’s midafternoon newsmagazine All Things Considered. “We go to that place, we choose a corner, a person, a house, a block, and go in there until we’ve answered all the natural questions that come up from that news story.”

Embedded is fundamentally intended to be a news podcast, and an expansive one — affording McEvers, her producers, and other reporters time to explore one specific area and follow up with its characters, sometimes even without the certainty of a story. (All Things Considered radio stories might run longer than most NPR news pieces, but 10 or 11 minutes is generally the upper limit.) It’s produced virtually all in the field. It’s a podcast that makes good and full use of NPR’s newsroom resources — “this is a podcast that from the get-go has come from the newsroom” — and versions of the stories will also appear on All Things Considered. McEvers herself will also join Tom Ashbrook on On Point to discuss episodes.

Embedded is fundamentally intended to be a news podcast, and an expansive one — affording McEvers, her producers, and other reporters time to explore one specific area and follow up with its characters, sometimes even without the certainty of a story. (All Things Considered radio stories might run longer than most NPR news pieces, but 10 or 11 minutes is generally the upper limit.) It’s produced virtually all in the field. It’s a podcast that makes good and full use of NPR’s newsroom resources — “this is a podcast that from the get-go has come from the newsroom” — and versions of the stories will also appear on All Things Considered. McEvers herself will also join Tom Ashbrook on On Point to discuss episodes.

McEvers spoke with me this week ahead of the podcast’s launch about the podcast’s very newsy origins, the way her radio and podcast experiences have been mutually beneficial, and letting listeners into the room where the journalism sausage is made. Our conversation, lightly edited for length and clarity, is below.

This is how I’ve always done things as a reporter: I listen and I read and I try to find the whole story. The idea of having 100 percent field reporting — this is just what I love to do.

One of the early experiments that lead to this happened last year. It was one of the early shootings by police of an unarmed black man and it was in Los Angeles on Skid Row. My editor at the time when I was a correspondent on the national desk said, grab this very talented producer we have here who’s already done a bunch of pieces, and just go and hang around Skid Row for a bunch of time, and see what it feels like to go and spend longer reporting something and turning it into a longer form story. And that’s how this all got started. This is exactly how we do our news coverage, but it’s just a few extra days to spend to see what we might find.

We came back and put together a piece, and that piece will be in the first season of Embedded. It was only then that we realized that going out and choosing a place, based on a story you’ve seen in the news — that could be a cool format. How many times have you seen something in the news and thought to yourself, I want to know more? We go to that place, we choose a corner, a person, a house, a block, and go in there until we’ve answered all the natural questions that come up from that news story.If I was a freelancer sitting at home in my office, I could never have done this. What is the benefit of being surrounded by hundreds of people who are working in the news all the time? This is it. It’s people who are smart enough to say to me: Take some extra time, think about these other opinions around a news story.

The next story we reported is the one that will be the first episode of Embedded. It’s the one you heard in the trailer, from Indiana. The headline there was last February: HIV outbreak in Indiana. That’s one of those instances we covered so thoroughly, especially on All Things Considered. We interviewed a lot of people. But again, it’s one of those stories where you’re thinking: Man, I bet that in addition to the news magazine coverage we’re doing on this, it’s the kind of story that would really benefit from serious time on the ground. Not a whole lot more than you would do for your four-minute All Things Considered story — just a couple of extra days.

On the road for @npratc and #NPREmbedded w/ @TomDreisbach @jkhrpr & @jojopawlo in Austin, Indiana. Can't wait to share what we found!!!

— Kelly McEvers (@kellymcevers) March 14, 2016

We spent a total of six days in this one house where people are addicted to this specific drug at the center of this HIV outbreak. We had a series of questions. How do people start doing this drug? Why do they share needles? By just staying inside this one house, getting embedded, we answered those questions. Those answers were not comforting.

So this is a story where we did a lot of the reporting last spring, but we were just back there a week ago. We updated the podcast episode, we’re going to do material for All Things Considered. We took one trip to Indiana, and got all this material that go out on all these different platforms. We started last year but have been reporting on it over the course of the year.

This is the just like the kind of reporting you’d put in for a cover story for a Sunday magazine, or a story for a magazine like The New Yorker.

This is similar to what we did for Invisibilia, what we do with Planet Money, with Hidden Brain, NPR Politics podcast pieces we rerun on our show.

I wouldn’t say it’s twice the work, but I’m going to go with something along the lines of 1.7. 1.65?

The Indiana HIV story is a good example of how this should work. Because there was this lag time, we had to go back and re-report stuff. This isn’t just a piece of entertainment. It isn’t an episode of Mad Men we can put out and say, here it is! We have to find these people again, see what they’re doing. That dovetails perfectly with All Things Considered: One year later, the HIV outbreak, what’s happening? We can do that news story we would’ve done anyway, and also check in with all the people from our documentary piece. That was beautifully seamless. We also did a listening event for the podcast; I did some station stuff for NPR. It was three days in Indiana, and I would’ve been in Indiana for these days anyway for All Things Considered. I was able to do both things during that same amount of time.

One of the things we’ve learned from podcasts is that process is interesting to people. Raising the curtain a little — but not too much, the story is obviously not about you — to show: How did you get here? How did you find that biker dude in Texas?

I’ve ended up learning a lot about writing. I’ve always tried really, really hard in my radio stories to sound like a person. How would I tell this story to my friends? When my mom asks, “What are you working on?” and I say “Well, I just got back from Syria, and here’s what I found.” I always try to write a story like that anyway, but with a podcast even more so. You’re really trying to put yourself in a place of being a person very casually telling someone something, as opposed to this omniscient, all-knowing anchor-radio correspondent voice.

It sounds so easy to just say, be yourself. But it’s hard. I was saying to a good friend of mine in radio recently, that nobody told me how hard it would be to “be myself,” especially when I’m hosting. You sit in that chair, and the lights are on, and you’re in this specific role, and you can start to sound like somebody else, or somebody you think you’re supposed to be.

It sounds so easy to just say, be yourself. But it’s hard. I was saying to a good friend of mine in radio recently, that nobody told me how hard it would be to “be myself,” especially when I’m hosting. You sit in that chair, and the lights are on, and you’re in this specific role, and you can start to sound like somebody else, or somebody you think you’re supposed to be.

With podcasting, the demand for being yourself is even stronger. People really want to hear somebody who’s flawed, who makes mistakes, with false starts, someone who goes down bad rabbit holes and who doesn’t always have all the answers. You can say all that in a normal, transparent way. You can say: I screwed up. I should’ve done this. I didn’t do that. You can say, I was thinking one way, but I’ve now changed my mind, because I’m a human being. The personal aspect is something I’ve learned. When I sit down to write a podcast, I try to be in that place.

A lot of the great storytelling podcasts happen in the studio. I hope ours opens the door to people thinking more about what you can do in the field, when things don’t go as planned and are unexpected. Part of what we do is get embedded somewhere and just see what happens. That’s a little scary, a little risky, because sometimes things don’t happen. You might just have to be there until something does. I like that it’s riskier.

Hopefully this will spark others to do the same, to get out there, instead of planning it out in the studio, and finding that right person who’s going to say that perfect thing. This is something off of the news, something you know that there’s this initial interest for. You take that as your cue, go into the world, and wait for something to happen. It’s also a fun way to live.