Last year, for the first time ever, my husband and I bought a car. At the dealership, one of the first things that the sales guy wanted to show us was how to hook up our phones to the car’s Bluetooth entertainment system. When we said we’d be able to figure it out, he explained that enabling the technology for us was a dealership requirement. Apparently, Boch Toyota Norwood is assuming that a lot of people aren’t going to just turn on the radio in their new cars for their first drive home.

The audio listening habits that we’d acquired during years of public transportation-and-walking commutes came into our new car with us. We listen to the radio if our phones are low on batteries or if we’ve forgotten to download podcasts. Our two-year-old hates the radio and only wants to listen to music we’ve saved offline to our phones from Spotify. In dire tantrum situations, we’ll stream music, data plan be damned. Our car is the basic model — it doesn’t have its own Internet connection or anything like that. But its in-dash entertainment is good enough to let us skip the radio completely if we feel like it, and we usually do.

We’re used to hearing that young people are no longer reading newspapers or subscribing to cable. Logic would suggest that a similar transition is inevitable for radio. But radio is also in a unique, lucky spot because it’s usually free, it’s ubiquitous in cars, and it can be listened to as a form of background entertainment. So will it manage to escape newspapers’ fate?

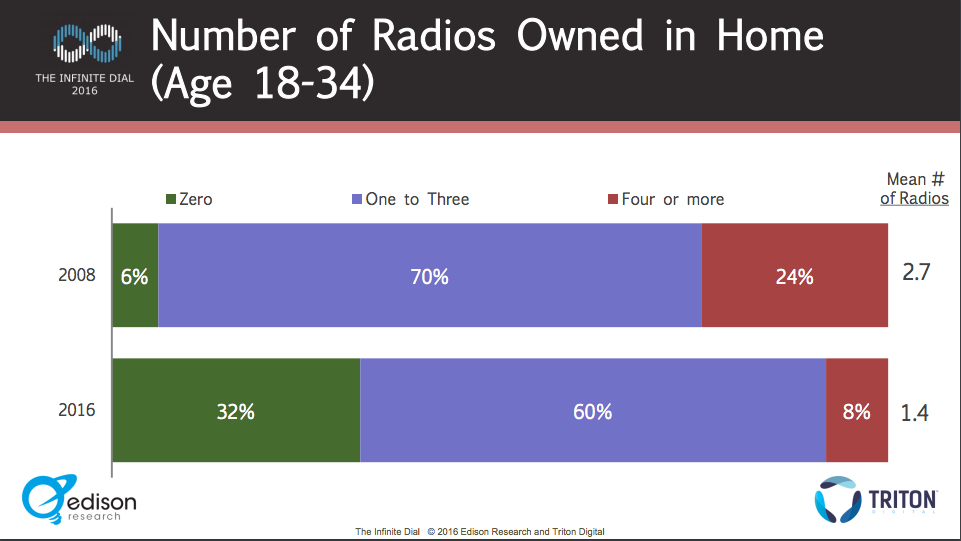

There’s good news and bad news. Ninety-three percent of U.S. adults listen to radio weekly, according to Nielsen. But a great deal of listening is shifting online. Fifty-seven percent of U.S. adults ages 12 and over had listened to online radio in the past month, according to the 2016 Infinite Dial report from Edison Research and Triton Digital, and the number of people who own a radio at home is decreasing: 96 percent of U.S. adults (and 94 percent of 18- to 34-year-olds) owned a radio in 2008; today, 79 percent of adults do, and just 68 percent of 18- to 34-year-olds do. (I had to wrack my brain to remember whether my household owns a radio besides the one in our car. We do, I realized — a clock radio whose clock has been broken for months. If we replace it, it will be because we need a new bedroom clock, not because we need a new radio.)

Pew noted in 2012 that the percentage of Americans who get news from the radio has “steadily declined over the past two decades.” In 1991, 54 percent of Americans said they had listened to radio news “yesterday.” By 2012, that figure was down to 33 percent of Americans and just 20 percent of 18- to 24-year-olds. 2012 is the most recent year that Pew asked this specific question, but it seems safe to assume that the figures have continued to fall.

Look at the big commercial radio companies in the U.S., and you get a pretty gloomy picture. iHeartMedia (formerly Clear Channel), the largest radio company in the U.S. with 850 stations, currently trades for just around a dollar a share, down from around $6 last April. The company is loaded down with debt, and restructuring or bankruptcy could be in its future. Cumulus Media, which owns 454 stations, trades at just $0.54 a share, and NASDAQ has warned that its share price is so low it could be delisted. Emmis Communications stock trades under a dollar. And CBS announced last month that it is planning to sell off its radio stations.

CBS “marks the last of the legacy network broadcasters — NBC, ABC, and now CBS leaving the business,” Steve Goldstein, the CEO of podcast company Amplifi Media and a longtime radio exec, told RAIN News. “In that sense, it is a huge story. Even in a world in which big media is focused on multiplatform solutions, linear radio doesn’t seem to be a priority.”

But what does the decline of these big companies really signify about radio’s overall situation in the U.S.? “If you look at the commercial end of things, your big publicly traded companies, I do not think that you can look at their stock situation or their profit situation as an indicator of the health of radio as a medium,” Paul Riismandel, the cofounder and operations director of radio news blog RadioSurvivor.com. “When you look at how many people actually listen to the radio every week, every day, those numbers are very healthy. The problem with looking at commercial radio, specifically the biggest companies, is that they were built on debt.”

The decline in commercial U.S. radio stocks appears to be “partially driven by a belief that things are changing rather faster than they actually are,” James Cridland, a radio analyst (and “radio futurologist”) based in Australia, told me.

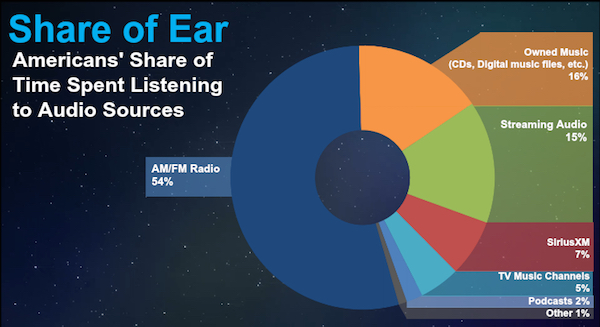

But even if change is slow, as Cridland argues, it is happening. For its ongoing “Share of Ear” study, media research firm Edison Research does quarterly polling of a group of 2,021 Americans ages 13 and older about their audio listening habits. Edison asks respondents not just whether they listen to the radio at all, but how much they listen to it compared to other forms of audio.

Here you can see habits changing. For the quarter ending December 31, 2015, Edison found that, among all ages polled, Americans spent 54 percent of their listening time on AM/FM radio, with streaming audio at a distant 15 percent.

Among 18- to 24-year-olds, however, for the first time, streaming audio beat out AM/FM radio as the top source of listening. (For teens ages 13 to 17, the listening habits are similar. The 25- to 34-year-old age group is the next highest in terms of streaming, and streaming becomes progressively less popular with each older age group.)

“This advantage comes despite the fact that for audio consumption in the car, streaming is as yet quite small,” Edison Research cofounder and president Larry Rosin wrote. “Streaming wins at home and at work in sufficient amounts to surpass radio overall.”

The car factor makes things tricky when it comes to analyzing the future of radio listening. Half of all AM/FM radio listening in the United States takes place in the car. As younger groups start entering the workforce in larger numbers — and, presumably, driving to work in larger numbers — will they start listening to the radio more often, as older generations do?“That’s totally plausible,” Rosin told me. “Working full-time definitely does seem to be a factor in radio listening, almost entirely because [people who work full-time] spend more time in their cars.” Still, he pointed out, young people take their new media consumption habits with them as they get older — as my husband and I did when we bought a car for the first time in our 30s.

He elaborated on this idea in a podcast interview with the website Hypebot: “Radio does better and better as people get older and older. I do not think this is a function of people liking radio more as they age. I think this is a function of the younger you are, the more likely you are to have explored other options for the audio consumption.”

Cars will change, too: With newer cars come more advanced dashboards, more compatibility with smartphones, and more independent Internet connections. (And, though miles driven has rebounded in the last couple of years, Americans are still driving less than they did before the financial crisis in 2008.) So the U.S. industry might want to take a cue from Radioplayer, a nonprofit partnership between the BBC and commercial radio stations in the U.K. that is expanding its model to other countries.

“We’re a bunch of broadcasters who got together about five years ago and said, what if we worked across the industry on stuff where appropriate, but continued to beat the hell out of each other in competition in other areas. The mantra was: Collaborate on technology, compete on content,” Radioplayer U.K. managing director Michael Hill told me. Radioplayer’s first product was a web player and search engine for live and on-demand content; it’s now used by 400 stations across the U.K. Next up came mobile apps; now Radioplayer is working on radio in cars and on hybrid radio, which is a mixture of broadcast and IP-based radio.

Radioplayer has since licensed its technology to other countries, including Germany, Austria, Ireland, Belgium, and Norway; Hill is also in talks with other countries, like Canada. What about the U.S.?

Whenever I speak to radio professionals from America, even though on the face of it they’ve got all these aggregation, digital, and commercial models going, they are universally pessimistic about the future of American radio,” Hill said. “They’re so down on themselves. I wouldn’t claim that Radioplayer singlehandedly boosted the attitude of European radio, but it was a part of it: Choosing to work together in a spirit of optimism is a part of having a successful future as a medium. Whereas all choosing to sit in their own buckets and die alone is how it feels like some of American radio sees its future.”

Hill sees particular opportunity in cars. New cars are increasingly built with touchscreen dashboards and integration with smartphones and various web apps — all listening choices that compete with terrestrial radio. “The biggest danger to radio in cars is not people stopping listening because they like other things. It’s car companies failing to understand the importance of radio in cars to their consumers, and leaving it out, or designing it badly — putting on the seventh screen down in a menu, failing to evolve the interface so it still looks like something out of the ’80s while all the other music services look great with album art and Now Playing information on the screen,” Hill said.

When Radioplayer began setting up meetings with car companies, execs — not surprisingly — asked for proof that radio was important to drivers. Radioplayer didn’t have that research, and couldn’t find it previously published, so they went out and conducted it. The company sampled 1,500 people across the U.K., German, and France (the three main car markets in Europe), all of whom had bought a new car in the last three years, with the aim of proving how important radio is to drivers. (Of course, they’re an interested party here.)

What they found was that “radio was overwhelmingly the most popular medium in the car,” Hill said. In the survey, which concluded in December, Radioplayer found that 82 percent of drivers said they wouldn’t consider buying a car that didn’t have a radio. Of all in-car listening, 75 percent was to the radio (even in these modern cars equipped with other entertainment options in the dashboard), and 84 percent of respondents said they always or mostly listened to the radio on every journey. When Radioplayer asked respondents which entertainment option they’d choose if they could only have one, 70 percent chose radio. (Eleven percent chose CDs, and 1 percent chose music streaming.)There were few differences in preference by age (78 percent of 20- to 29-year-olds, the youngest group surveyed, said they wouldn’t buy a car without a radio in it) or by the kind of car the respondent owned.

I asked Hill what his ideal car dashboard would look like. “A huge radio and nothing else!” he said — joking, sort of, but serious that “radio would still have primacy, front and center.”

“That’s always been the problem with radio: We’re taken for granted,” he said. “That’s a good thing, but a bad thing when it comes to people making critical decisions about the future of car dashboards.” People in the U.S. drive their cars for, on average, 11 years. If carmakers “make the wrong decision, we’re locked into it, and radio starts to become harder and less safe to use in the car.”

So Radioplayer is talking with individual car companies. “We’re not just talking to the engineers who make the dashboards, but with the tuner guys, the guys who make the antenna on the roof, the marketers, the product development guys, the bosses of the car companies,” Hill said. “They are the ones who are deciding on the future.”

That’s assuming that the people who will be buying their cars one day aren’t already choosing a different future for themselves. Still, Edison’s Rosin noted, there might be room for everything. “The pie is getting bigger,” he said. “The total amount of audio usage is clearly growing because audio is available in more ways. If one form goes up, the others don’t have to go down.”

That said, there might be room for everything in a dashboard interface — but there’s usually only room for one thing in your ears at a time. And the “young people will eventually come around to old media” story is one newspaper veterans will remember — and not in a good way.