For such a new technology, the news notification is a format that got really safe really quickly. For most publishers, notifications are rarely more complex than a headline that, when tapped, sends readers to their site. Some publishers, like Quartz and BuzzFeed, have experimented with the language within notifications, trading the stiff formality of newspaper headlines for a more loose, conversational tone. But notifications, and their role, have remained largely unchanged.

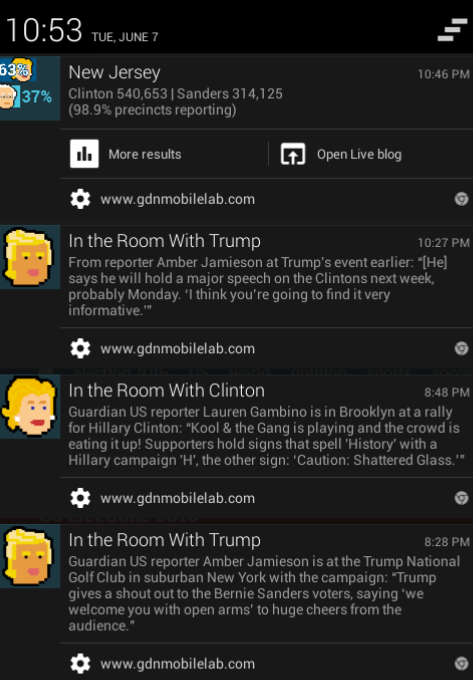

The Guardian Mobile Innovation Lab thinks there’s still plenty of room for innovation, however. For its coverage of last night’s presidential votes, the publisher experimented with a handful of new notification formats. For each state holding a primary, for example, The Guardian created notifications that automatically refreshed themselves as more results came in. With another format, called “In the Room,” The Guardian pushed out alerts about specific candidates, including quotes and scenes from campaign events — each joined by a pixel art illustration of the candidate the notification was about. And the notifications, sent to readers who signed up to receive notifications from The Guardian Mobile Innovation Lab, weren’t sent through The Guardian’s mobile apps, but rather through Google’s Chrome browser on Android and desktop, which lets users opt-in to get notifications from specific websites.

Last night’s effort is the latest in a series of notifications projects, each increasingly complex, designed by the Guardian Mobile Innovation Lab. The five-person effort, announced last June alongside $2.6 million from the Knight Foundation, was created to find new ways to connect with and engage readers on mobile devices, via not only notifications, but though live coverage, video, contextual delivery, and content interaction as well. (Nieman Lab is a content partner with The Guardian’s project.)

Why notifications? It’s one area where The Guardian Mobile Innovation Lab knew it could make the biggest impact without a tremendous amount of effort, said Sasha Koren, editor of the Mobile Innovation Lab. “People are experimenting with notifications, but in a very muted way,” she said. “Right now, it’s mostly in tone and content. The strategies around how many alerts to send, and sending them around certain specific events, don’t really seem to be a big part of most orgs’ thinking so far.”

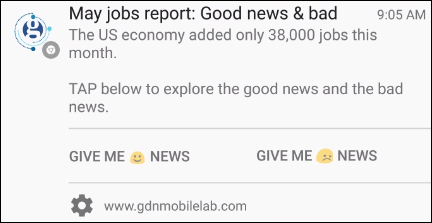

The Guardian’s election notifications are the third such effort from the group. For its first public-facing experiment last week, the group sent out push notifications to people interested in the latest jobs report numbers (which weren’t great, by the way). The notification included a social headline-like title (“May jobs report: Good news & bad”), a short subhead (“The US Economy only added 38,000 jobs this month”), but its most intriguing feature was the set of action buttons that let users decide whether they wanted good or bad news. Users who opted to see good news got positive numbers about the unemployment rate going down and wages going up. Opting for bad news meant reading about the rise of teen unemployment and the spike in people quitting their jobs. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, people were twice as likely to want the good news instead of the bad.)

While all of the notifications let readers clickthough to get to a longer story, the primary goal was to create notification formats that told stories in a new way, were interactive, and could satisfy users on their own. “We didn’t want to do something where we just slammed a headline on your homescreen and expected you to clickthrough to an article,” said product manager Sarah Schmalbach. She said that stories such as the jobs report are ideal because they benefit from being told in a more digestible, interactive format.

That kind of interactivity was a big part of what drew the Guardian Mobile Innovation Lab to Chrome’s web notifications, which are built into both the desktop and Android versions of the browser. Added last year, the feature lets websites send users app-like push notifications through Chrome itself. That’s nice for websites that don’t have the resources to develop their own apps but want to maintain a relationship with readers once those readers click away. It’s also good news for users, who don’t have to download a publishers’ app to get notifications about topics they care about.

That’s a big deal on the mobile world, where publishers are lucky if they can get someone to download their apps, and even luckier if they can get users to interact with those apps on the regular basis. 46 percent of people polled by Pew Research Center said they only used one to five apps per week. For individual news apps, it’s tough to give a critical mass of users enough reason to keep coming back. Opting for a web-based notification system changes that dynamic.

“Up until now, apps and notifications have been tied together, so you’ve always had to sell people on the idea of downloading the app in the first place,” said Alastair Coote, lead developer at the Guardian Mobile Innovation Lab. “With this, we can make the case for notifications without the app involved at all.”

The tech isn’t without its challenges, however. The biggest is that Chrome’s web notifications only work on Android and the desktop versions of Chrome, not on iOS. This significantly limits the number of potential users for The Guardian’s effort. Chrome’s web notifications haven’t been used or tested much outside of a handful of sites, which means that The Guardian’s mobile team regularly runs into new problem (such as some people not receiving notifications at all).

Score one for Android, live updating notifications are pretty great. pic.twitter.com/7gs9cqMrcf

— Zach Seward (@zseward) June 8, 2016

Those limitations limited the overall number of people who signed up for the alerts, but the team says its happy with the results. Of the roughly 100 people who signed up, around 50 percent actually got the initial jobs report notification because of technical issues. Of those, about 20 percent made it all the way through the multi-notification narrative, which Schmalbach said was promising and will increase over time as the behavior becomes more intuitive.

Ultimately, The Guardian’s notifications efforts fit into its larger effort to create fuller experiences for mobile, while not dumbing down the experience or playing into the idea that mobile readers means reduced attention spans.

“The concept of what a full experience is is relative based on the time you have and the interest you have in that topic. We talk a lot about crafting experiences around a story that meet people’s needs,” Schmalbach said. “There’s a 15-second version of a story and a five-minute version. Based on the time you have, where you are, and you interest in the topic, we’re trying to give you the version that is best for you.”