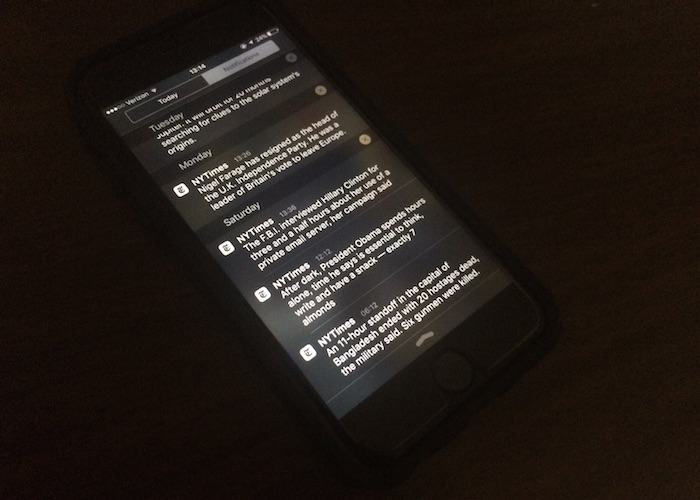

Readers who subscribe to New York Times news alerts got a surprising notification last Saturday morning: As part of his late-night routine, President Obama reads briefing papers and eats seven — yes, exactly seven — lightly salted almonds.

Readers who subscribe to New York Times news alerts got a surprising notification last Saturday morning: As part of his late-night routine, President Obama reads briefing papers and eats seven — yes, exactly seven — lightly salted almonds.

Dear @nytimes thanks for this important breaking news alert. Obama likes almonds, exactly seven, everyone! pic.twitter.com/kZInHqIsN5

— Tzipora Raphaella (@Tzipity) July 2, 2016

The Times sends out alerts for feature stories and special reports, from an exclusive interview with Paul Simon on his future plans to an article about Canadians welcoming Syrian refugees. While many readers appreciate being alerted to those types of stories, others complain that they only want to be alerted to breaking news.

Let's discuss what constitutes "send an alert to people's phones"-worthy news, @nytimes. pic.twitter.com/pCxxlOhrs2

— Tim Carvell (@timcarvell) June 29, 2016

Now readers are getting more options when it comes to alerts and notifications. In a message to subscribers on Thursday, the Times said it was creating two channels for its email news alerts, allowing readers to sign up for separate breaking news and top stories emails:

The Times plans to roll out a similar feature on its mobile apps in the coming weeks, said Eric Bishop, assistant editor for mobile.

“We see these channels as a way to expose readers to the breadth of our coverage, because we have a lot to offer that’s not news,” Bishop said. “We want to make sure that people can find out about those great stories, whether it’s via email or via push, but also be sensitive to those who don’t want to get that content on those channels.”

At the outset, existing email subscribers will receive both the breaking news and top stories emails.

When it comes to mobile alerts, the Times purposefully calls its main alerts “Top Stories,” in order to indicate that it also sends investigative and feature stories that aren’t breaking. With the update to the app, Bishop said the Times will make breaking news alerts their own category.

When it comes to mobile alerts, the Times purposefully calls its main alerts “Top Stories,” in order to indicate that it also sends investigative and feature stories that aren’t breaking. With the update to the app, Bishop said the Times will make breaking news alerts their own category.

Still, many readers do want to be alerted to stories like the one about Obama’s late-night habits, and separating the alerts categories allows the Times to give its readers more options.

“A lot of people saw [the Obama story] on their lock screens, swiped it and read the story,” he said. “We’re figuring out how much to do this — what type of language to use to describe stories like this, how to signal why we think it’s so important that we’re going to push it to your lock screen. Those are all very real questions that we wrestle with in the newsroom on a daily basis, but we do know that there’s an appetite for that type of stuff among readers. We also know that some readers see that space as something that should be reserved for breaking news only.”

The Times first introduced specialized mobile notifications in 2014. Those allow users of the paper’s apps to subscribe to alerts on topics like business, politics, and sports.

Meaning: If you didn’t opt-in to our politics channel on NYT iOS app, you wouldn’t see that push alert. Tap the bell icon, check it out!

— Michael Roston (@michaelroston) July 23, 2014

Despite the choices that readers already have, deciding when to send a push alert can be a challenge. A story in The Atlantic on Friday questioned why the Times decided to send the mobile alert last weekend about the story on President Obama’s late-night habits, but didn’t send one about the suicide bombing in Baghdad that killed at least 250 people.

A Times spokesperson told The Atlantic that there were two reasons the Times decided not to send an alert on the Baghdad attack:

Last summer, as part of a series I wrote about how newsrooms approach push alerts, New York Times news editor Karron Skog said that Times editors frequently debate whether to send an alert on a story when it might be late. More often than not, she said, the Times decides to send the notification:By the time we confirmed key details on the scope of the bombing and had our own staff-reported story, the news was several hours old and we decided a push would feel stale. Also, we had sent six push notifications over the holiday weekend and did not want to overwhelm readers.

We wrestle with ourselves about this on the news desk. We may feel like we’re late on an alert, or maybe we’re not even late, maybe we just waited longer than other news organizations because we had an extra detail that we wanted to add. We’ll have this debate: Should we alert it now? It seems late, but readers aren’t staring at their phones and checking their alerts constantly the way we are. People might come to it an hour from now, or it might be three hours from now. If they do, they’ll find an updated story. That stub of an article keeps refreshing with everything new. So we feel that it’s worth it, even if we’re going to be a little late.

When it comes to alerting feature stories, the Times tries “really hard to think about whether something is really worth alerting,” Skog said. “Is it something we’ve put a lot of time into, that Times readers are going to want to know is out there?”

We’re mindful of the fact that it may irritate our readers when they get alerts about things that aren’t breaking news. We’ve been very careful about how we craft the wording for those things and how many of them we do.