Editor’s note: The first three chapters of a remarkable new document, A Field Guide to Fake News, are being released at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia. The guide, the work of a team of scholars, explores new and more subtle ways of looking at the fake news phenomenon — and, through it, how our lives are mediated in an age of data, platforms and algorithms. Below, three of its coauthors summarize some of what they’ve found; don’t forget to check out the full document.

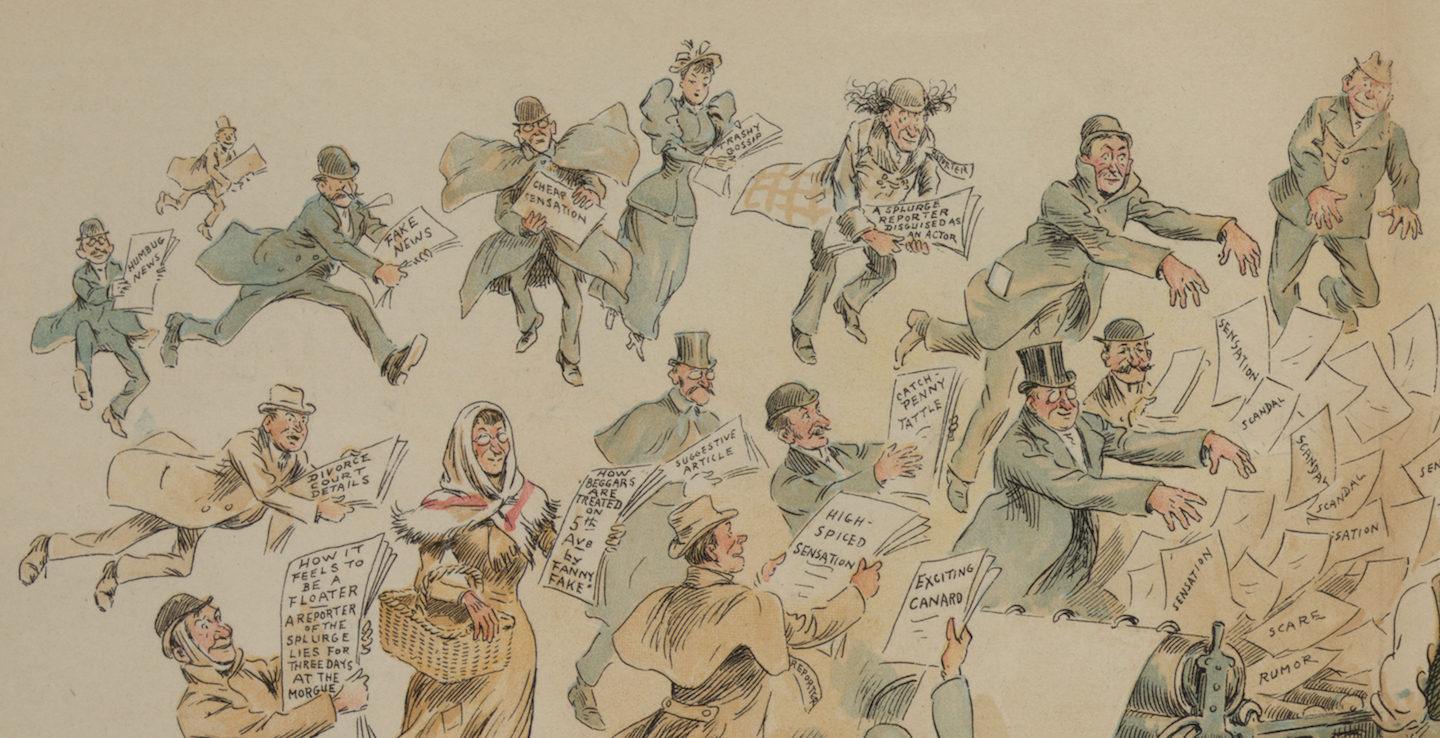

Five months after the U.S. elections, fake news remains high on media, political, and public agendas, having sparked a wave of concern, responses, and counter-responses in countries around the world.

Media and technology companies have established major new projects and charged ten-thousand-person units with dealing with it — leading to concerns about “band-aid solutionism.” Governments and public institutions have launched consultations, programs, and investigations to research and respond to the issue, including state-sponsored debunking initiatives in regions from Russia to the European Union, as well as proposals for multi-million euro fines.

The term has become a keyword for both media institutions and the political mobilizations who contest them. Driven by countless reports, position papers, analyses, columns, reflections, op-eds, startups, imitators, accusations, and parodies, and despite numerous attempts to declare the issue “dead,” “meaningless,” or itself “fake” — the issue endures, like a prolonged argument where no one’s able to have the last word.

The term has become a keyword for both media institutions and the political mobilizations who contest them. Driven by countless reports, position papers, analyses, columns, reflections, op-eds, startups, imitators, accusations, and parodies, and despite numerous attempts to declare the issue “dead,” “meaningless,” or itself “fake” — the issue endures, like a prolonged argument where no one’s able to have the last word.

Amidst all of the panic, finger-pointing, hype, bandwagons, and fatigue, what are we to make of this highly mediatized and politicized issue? How are we to understand and collectively respond to the phenomena which are the center of concern? As a network of researchers specialising in digital methods for social, political, and cultural inquiry, over the past few months, we’ve been engaged in a number of projects to trace the production, circulation, and reception of fake news online — and to see how we might bring fresh perspectives and unfamiliar angles to the public debate.

It’s a fascinating object of inquiry — not in spite of but precisely because of its highly contested and hotly debated character — which tells us just as much about the character of infrastructures and social institutions whose functioning we may not usually notice as it does about their weaknesses, failings, and blind spots.

The concern is not just that these infrastructures and institutions are being gamed and exploited (as they routinely are by advertisers, media, and technology companies, politicians, and by many other organizations and professions), but rather the feeling that the social rules and norms that normally bind us together are being violated — whether for fun, profit, or (geo-)political gain.

But in following fake news online, we encounter not just rogue producers, state propagandists, geopolitical fault lines and hyperpartisan mobilizations. We also learn about the patterning and politics of collective life online, and the consequences and logics of the different technological and economic modes of organization that undergird it.

Here we have the uncanny feeling that, in hot pursuit of the perpetrator, we discover a trail of evidence leading to our own doors. As media scholars Mike Ananny and Kate Crawford recently pointed out, the platforms and algorithms at the center of fake news controversies can be understood not just as “black boxes,” but also as “relational achievements” that involve and evolve alongside our own lives online.

One can certainly make the point that the person holding the weapon is not necessarily the only one with blood on their hands. But we also wish to suggest that the issue of fake news can be leveraged as an opportunity for public reflection, political economic imagination, and more thoughtful, attentive, and potentially ambitious interventions around the organization of the platforms and infrastructures which pattern our lives in the digital age.

Beyond becoming more efficient and effective at what is often described as the “whack-a-mole” game of cracking down on fake news (including using new technologies to semi-automate social and political acts of judgment and classification), what can we learn about our societies, ourselves, and life in an age of digitization, datafication, and platformization? How might we effect a shift from thinner descriptions of fake news producers and their strategies towards thicker descriptions of the ecologies in which they thrive? And what and how might we learn from these richer accounts?

Below are four ways of seeing fake news differently, drawing on our ongoing research collaborations around A Field Guide to Fake News with the Public Data Lab. The guide focuses not on findings or solutions, but on starting points for collective inquiry, debate, and deliberation around how we understand and respond to fake news — and the broader questions they raise about the future of the data society.

As many have pointed out, there are many different kinds of fake news. Or, as we put it in a forthcoming paper with colleagues, there are many different “shades of fakeness.”1 So much is evident in what one might call “controversies of classification” (around a list of false, misleading, clickbaity, and satirical sources by Melissa Zimdars, for instance), as well as in difficulties encountered around early attempts to fully automate the identification of fake news.

We have sought to develop digital methods and approaches for exploring what has been associated with the “fake news” label. One thing we established was that the meaning and significance of a given piece of content can vary significantly over time and across different settings. For example, from tracing the life cycles of fake news on Google search engine results, we found that a story that starts life as explicitly satirical can become “laundered” into clickbait and shared as a news source, and then shared again as an example of hyperpartisan misinformation or geopolitical disinformation.

Just as with works of art or literature, the meaning of a fake news story or image cannot be sharply separated from different ways of seeing, cultures of reading, or traditions of interpretation around it. Rather than focusing exclusively on its formal properties in terms of binary conceptions of “facticity,” truth value, or informational content, this would suggest a richer look at the settings in which it is shared and the breadth of meaning-making practices around it — whether satire or solidarity, irony or provocation, resentment or condemnation.

It is not simply by virtue of its “falseness” that something becomes fake news, but also through the character of its circulation — including the speed, scale, and nature of sharing. In particular, recent concerns around fake news are directly related to the threat of its accelerated circulation on the web and online platforms. Hence many attempts to fight fake news focus on material which is trending or gaining significant traction or engagement online.

In the Field Guide, we suggest that this circulation represents more than just the popularity of fake news, but is itself an integral part of understanding what it is and what it means. We also look at ways to explore this circulation beyond the aggregated counts of likes, links, shares, or posts that are often included as part of off-the-shelf social media metrics.

By looking more closely at how fake news moves and mobilizes people, we can develop a richer picture of not only how much it circulates where, but also why it circulates and how it resonates amongst different publics. For example, on Facebook we can look not just at total shares, but also the specific public groups and pages where it is shared, as well as a closer qualitative analysis of how it is shared and what is meant by sharing it.

Understanding this is also critical to ensuring that responses are attuned to the phenomena that they seek to address.

“Thicker” accounts of how fake news circulates may also suggest the limits of approaches to fake news that predominantly focus on fact-checking, debunking, and flagging fake news items — which might imply that fake news thrives because of a deficit of factual information, downplaying its affective resonance or emotional appeal.

Over the past few decades, many responses to misinformation have focused on mapping and debunking claims made or repeated by politicians, journalists, or other public figures. In the guide, we explore ways of looking beyond the content and circulation of claims by examining the technical infrastructures and economic models which underpin them.

For example, we look at how data about web trackers can be used to understand things like how fake news websites are associated, how they may make money, how their economic models differ from mainstream media organizations’, and how they change over time. We also explored this in a recent collaboration with Craig Silverman and his colleagues at BuzzFeed News.

Of course, this tells us not only about how fake news websites make money, but about the broader political economic organization of the web and digital platforms, and their associated advertising networks and partners.

Finally, we look at different ways of exploring responses to fake news — including their methods and publics. While many fact-checking initiatives focus on providing “truthy” followup articles and “factish” corrections, we look at where these circulate and how successful they are at reaching the publics of fake news on different platforms and in different settings.

For example, we examine how to compare the Facebook groups where popular fake news articles are shared, and the groups where fact-checking responses gain traction. In the case of a set of highly shared fake news stories, the most widely shared fact-checking responses only appeared in a handful of the hundreds of groups where the former were circulated.

Just as social researchers have become accustomed to working with “the shadows cast by our presence as explorers in the field,” as Shannon Mattern puts it, so we might hope that conceptions of journalistic objectivity might come to include the role that journalists and media organizations themselves play in shaping norms, expectations, and institutions of knowledge production in the digital age — as well as ways to understand and relate to so-called “post-truth” publics who feel that these institutions are failing them.

Jonathan Gray of the Institute for Policy Research at the University of Bath, Liliana Bounegru of the University of Groningen and the University of Ghent, and Tommaso Venturini of the Institute of Complex Systems at the University of Lyon are cofounders of the Public Data Lab.