Civic journalism, advocacy journalism, engagement journalism: All are buzzwords in the industry right now, particularly as the Internet allows groups underrepresented in the mainstream media to stake their own claims and amplify their own voices.

But Anna Simonton, an Atlanta-based freelance reporter and researcher for racial and economic justice nonprofit Project South, hopes that “movement journalism” creates a strong impact — and she plans to lead it by starting her own collaborative media organization. (Simonton also edits Scalawag, a magazine of Southern politics and culture and is on the board of a community radio station, WRFG, in Atlanta.)

Simonton recently took a deep dive into the community and minority-owned media landscape of the American South — so deep, in fact, that she spent over a year researching and reporting her findings in a 62-page report called Out of Struggle. Her report takes stock of the independent media landscape in the 13 states of the traditional South, from Texas to Florida to West Virginia, and was commissioned by Project South.

“We have good stuff that people are doing, [but] it’s very localized. How do we strengthen that and expand that impact?” she told me. “That’s what we think we can bring to the mix: finding some ways to offer services, support, training, et cetera, to increase the amount of journalism that’s going on in these already existing media outlets.”

This endeavor is geared toward connecting existing media groups and community and minority-owned news outlets, as well as producing original reporting about social justice movements in the region. It also aims to cross the digital divide that separates many news organizations, especially those who are exclusively online, from potential audiences. Next up: Simonton’s bringing the project to the Southern Movement Assembly, a gathering of 600 people organized by Project South in Whittaker, North Carolina this October.

I spoke with her last week — before this weekend’s violence in Charlottesville — about her experience with movement journalism and how digital-based news fits into the landscape of the South. Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation.

Christine Schmidt: What made you think this study was needed?

Anna Simonton: After college and an internship [at liberal magazine

The Nation], it felt like the next steps would be a job in New York City or San Francisco or D.C., somewhere in the realm of progressive-leaning media, because I knew that was my place as a journalist. I wanted to come home to the South for various reasons and see if I could find an outlet like that essentially to work at. There are some, but our independent media environment here is just not as robust as it is in the hubs, in the big cities on the coasts and D.C. I went at it on my own as a freelancer and learned a lot that way, did end up doing what I think is some meaningful reporting…on things going on in the South that weren’t getting covered.

We think that we need more coverage of people who are taking action to change their lives for the better, more reporting that sheds light on the forces they are up against — how is oppression functioning, why do these problems exist, who is responsible for them. Through our own experiences, we felt we needed this sort of journalism, starting with a research phase to this open-ended project of developing and launching something. We said, “Let’s really map the independent media landscape and find out what people are already doing and strengthen that, then create something original to fill in whatever gaps may exist.”

Schmidt: What makes movement journalism different from advocacy journalism?

Simonton: It’s something that I’m still thinking through. In some ways, it’s a bit of semantics, but advocacy journalism is in the same tent. There’s something about the term “advocacy” that almost implies you may or may not have a journalist have a stake in this, or that there may or may not be people outside of you that are doing something about it. You might be the journalist writing about this thing saying some change needs to happen and you might be acting individually. Movement journalism is about realizing there are people who are trying to build collective power and organizing together to make fundamental shifts in the power dynamics of our society. That’s our priority in terms of coverage.

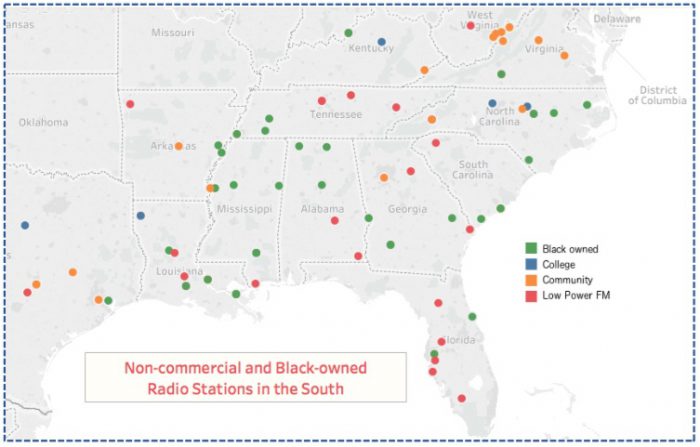

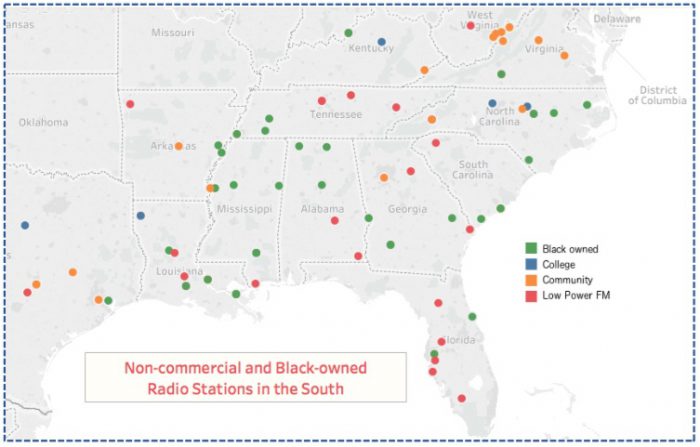

Schmidt: In the report, you tallied the number of alternative media outlets in the 13 southern states and found 91 radio stations, 25 public access television stations, 85 black-owned newspapers, 28 alternative weekly papers, 9 street newspapers, and various local print and online publications. What has the community and minority-owned digital landscape been like?

Simonton: With digital, honestly, some of the research on that was ad hoc. I didn’t arise on a really concrete method for comprehensively identifying the digital media landscape of the South. It was whatever came across my radar and if I could dig in and find a trail of breadcrumbs. Most print outlets have their online presence and especially for these big regional publications like

Facing South and the

Oxford American and Scalawag. On the local level, there’s a huge range. What some people would all citizen journalism in local areas for people who may not have a journalism background have taken it seriously and done really good reporting. It includes people who have gotten laid off through the upheaval of the journalism industry.

Schmidt: You also noted in the report that there is a divide between those who access the Internet and those who can’t access it, especially in the South. What are some of the best ways, in your opinion, for news organizations to cross that divide, especially for digital-based organizations?

Simonton: A brilliant way to do it is where there’s a digital home for southern regional reporting that gets tweaked a bit for a local angle for partners on the ground. It can get disseminated in a way that attempts to bridge the digital divide. Or you put it online first and then take that into a monthly roundup of that reporting and producing a little newspaper that gets distributed all over the place. Radio is a huge one — I want to start with print and radio [with the media organization she’s developing].

Schmidt: Right, because with audio you can put that online as a podcast or on air as a radio program.

Simonton: Yes, radio feels like the most salient way to me to not only bridge the digital divide but also the literacy divide. It’s in such a heyday right now.

Schmidt: Can you tell me more about the member-owned cooperative model that you said has strong potential in your report? What funding options have you discovered through your research?

Simonton: The main one is the

Banyan Project. It’s online-only, based in a small town in Massachusetts, but their basic idea is to have these hyperlocal online-only news sites that are funded through a

$36 annual membership. In some way, it’s not too different from how we fund public radio because that’s membership driven as well, but in the Banyan model, members not only have the great benefit of journalism as they need but they also have tangible benefits on top of that like voting power over the director. I think that we’re interested in taking that and saying: What would it look like if a community owned its own news outlet? There’s one in Canada that has started an online community news co-op that creates this incredibly direct relationship between the people producing news and the community that this news is for and about and that’s a big part of what we want. It’s inherent to movement journalism.

Schmidt:What’s something that surprised you in your findings?

Simonton: What surprised me was how much we do have in the South. As I mentioned, coming back [from cities with a lot of media like New York City], it’s easy to look around and feel like there’s a pretty bleak picture. That’s true in a lot of ways. As I started to do this mapping and reaching out to folks, it was amazing to me to be able to look at this map of 91 radio stations and it covers 13 states. We have good stuff that people are doing, [but] it’s very localized. How do we strengthen that and expand that impact?

I was also surprised by people’s eagerness and willingness, because a lot of these folks [in media] are under-resourced in a way that’s “get through the day and keep the lights on.” Not all these places are doing journalism per se, they’re definitely meeting a need in terms of information in their community but it may not include original reporting. That’s what we think we can bring to the mix: finding some ways to offer services, support, training, et cetera to increase the amount of journalism that’s going on in these already existing media outlets. This is something a lot of people do want — “If you can find a way to make this happen, we will participate!”

Schmidt: What is the timeline like for this endeavor going forward?

Simonton: Now, the development phase is taking this body of knowledge that we’ve collected and already vetted through a roundtable we had with some of the folks featured in the report. Does this report reflect everything that it could? Are there glaring gaps? It was a long process and that was important to us, that our processes are as collaborative as we’re saying is important in journalism. Moving on from here into development and the launch phase, I could see development taking another year as we fundraise and in order to be able to bring more people onto a core team. The ultimate goal is to launch separate from Project South. This will not be a project within their org; they’re incubating it.

Image of the

Greene County Democrat team in Alabama provided by Anna Simonton. The current owners bought out their successors after picketing and boycotting them for what they considered racist coverage in the 1980s and have run the paper ever since, which Simonton describes as a prime example of movement journalism.