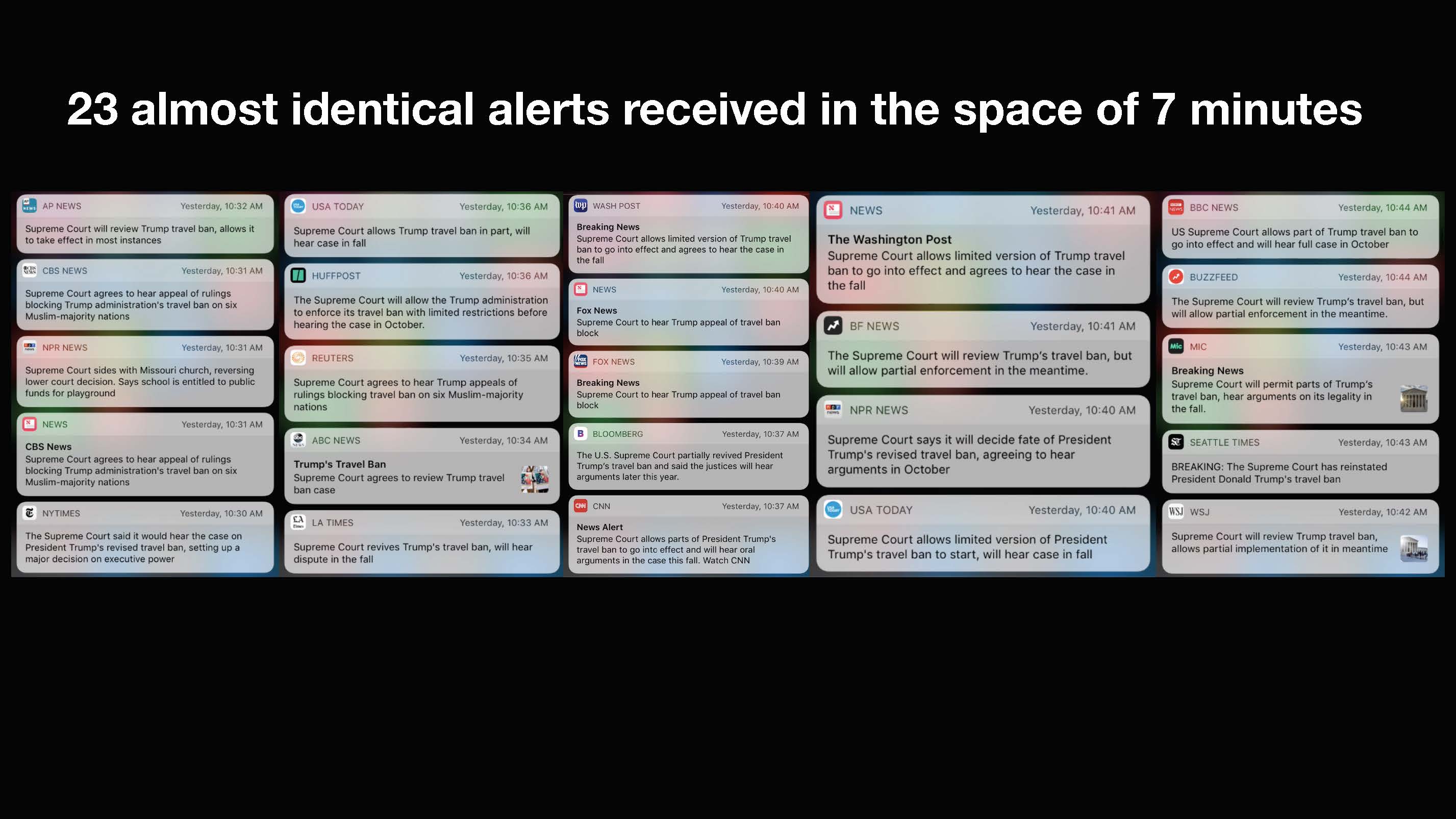

How many push alerts is too many? What are the biggest challenges for news organizations sending out alerts? What happens if readers don’t even click through?

Upcoming research from the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia and the Guardian U.S. Mobile Innovation Lab takes a look at how news organizations are sending out push notifications. A preview of the research was presented at the Online News Association’s annual conference last week, and the full report will be released in November.

Pete Brown, a senior research fellow at Tow, led the analysis, monitoring alerts from 31 iOS apps, as well as Apple News, over three weeks between June and July 2017. (This was an iOS-only study.) This turned up a sample of 2,577 alerts. Brown also conducted 20 interviews with mobile editors, product managers, and audience managers (all of whom remained anonymous).

Most of the alerts coming from apps were breaking news, 57 percent (although clearly, organizations have different definitions of breaking news). It’s different for Apple News: 74 percent of alerts there were for non-breaking news.

Brown divided the types of iOS app alerts into four categories.

“Additional context” alerts were the most common (55 percent), followed by headline (25 percent), teaser (11 percent), and roundup (8 percent). (The remaining 1 percent were classified as “other.”)

In addition to sending the most alerts overall, CNN MoneyStream also used by far the most emojis in its alerts.

Some of the main challenges that Brown identified for publishers:

— Standing out on an increasingly crowded lockscreen.— Clunky tools. “We’re limited by the tool that we use because, for breaking news at least, we use the same tool to send out the push alerts as we do to send the tweet and to put the banner on the homepage, so it’s all wrapped up in one tool,” one mobile editor said. “I think in certain cases we do the push alert a disservice because we’re trying to meet other needs with the same tool.”

— Segmenting audiences and sending out personalized alerts is very difficult. “We had a look at the levels of segmentation that were on offer for the different apps we include, and that ranged from from 1 or 2 all the way up to 52, in one instance, where you could get injury news for specific college teams,” Brown said. Other apps offer no personalization at all beyond the ability to opt in or out of alerts.

One fear is that personalization will create as many problems as it solves. “Some people envisage a future where people can, essentially, get personalized alerts about the most minute things. As soon as an article goes out about a subject they’re interested in, they’re going to get an alert about it,” Brown said. “But that doesn’t sit nicely with the idea of crafting the best push alert you can. If it’s going to be automated, it’s likely to be just a headline” — otherwise, it involves coordination across an entire newsroom and major workflow changes.

“The more personalized notifications become, the more you’re running the risk of getting into a filter bubble in an area where we once had a fair bit of control,” Brown said. But if people don’t like the alerts, they’ll just turn them off, “which is what the publishers don’t want them to do.”

— Local outlets are struggling to figure out how much national and global news their audiences want pushed out. “We’re just struggling to figure out exactly where we fall for readers, because obviously we are the go-to source for [city] news; for many, statewide news; and for some people, Midwest news,” the mobile editor at a regional outlet said.

— The audience isn’t always aware that push alerts can be clicked on to expand them. Mic and USA Today, for instance, are embedding photos and videos within alerts. “There’s a concern that if audiences don’t know you can expand an alert, then they’re not going to see the great work people are doing,” Brown said.

Rich notifications are also an area that Apple and Google control, which is a bit troubling. “Rich notifications were available quite a lot earlier on Android than they were on Apple,” Brown said.

— There aren’t good metrics. “Possibly the most recurrent thing that came across when we talked about challenges,” Brown said. “There are so many things that we can look at with a regular story that we cannot do with push,” said one mobile editor. It’s hard to know what makes a “successful” alert beyond the number of times it’s opened.

— Publishers don’t know whether audiences “value their alerts.” “I think a successful push notification is one where somebody opens their phone, looks at it, says, ‘That’s interesting,’ and puts their phone back in their pocket,” one editor at a “specialist news outlet” said. “All I want is for our readers to feel like they’re informed or they’re interested. If the pushes do that, to me that’s success and that’s fine.”

“This really surprised me, and it came up again. I’d ask people in every interview what they consider a successful push alert,” Brown said. Nobody knew. “They’d say, ‘What I consider a successful push alert might not be what my boss considers a successful push alert.’ I think there’s a real need for some kind of qualitative effort — data into how engaged people are with push alerts, to give newsrooms the information they need about what does and doesn’t work.”

If people aren’t actually opening alerts, though, will that start cutting into publishers’ traffic?

“This is something I can’t quite get my head around. The whole notion of creating content just for the lockscreen feels a little bit, to me, like creating content for Apple or Google or the mobile operating system,” Brown said. “I worry that, down the line, people will be having conversations about the mistakes of that — in the same way that people are worried now about creating content just for Facebook or Apple News.”