The Jordan-based podcast network Sowt isn’t offering any newfangled technology. But as a platform that both curates and produces its own original, high-quality Arabic-language narrative content, it’s already a rarity in the Middle East.

“The Arab youth now seems to keep an eye on what’s out there in terms of good podcasts in their own language, and topics that fit their social interests more,” and are tired of having only American content to listen to, Hazem Zureiqat, CEO and co-founder of Sowt, told me. “We have to exploit this need from now on.”The five members of the team — which includes freelancers and staff producers — officially launched Sowt as a podcasting brand a year ago. The network now offers three longer-form original shows and two shorter ones. It launched a sixth show at the end of December called Razan, covering the world of Syrian activism post-2011.

Today, Sowt is one of the more prominent names in the Arab podcasting landscape, one that understood early the potential of an audience hungry for better audio storytelling in a region where the podcasting market is still in its infancy.

But Sowt had a previous life. Amid the Arab uprisings, Zureiqat, an MIT-graduate engineer and active member of Jordan’s tech scene, launched Sowt — Arabic for “voice” — as a social network where users could share short audio clips on a timeline or feed. The platform was structured like Twitter (and audio apps like Anchor or Bumpers), with audio clips rather than limited-character tweets.

It didn’t last long: “It wasn’t generating income and didn’t get a large enough user base to be sold,” but did manage to register a few patents, according to Ramsey Tesdell, a friend of Zureiqat’s who is now a managing partner at Sowt. (Tesdell is also a past Nieman Lab contributor.) Tesdell saw that audio storytelling online still had plenty of room to grow in a region with a rich oral tradition. He helped Zureiqat turn the original Sowt into its current iteration as an Arabic podcast producer and curator. (For the new Sowt, Zureiqat and Tesdell used the same website and underlying infrastructure that had already been built for the Twitter-for-audio iteration of Sowt — Zureiqat already owned the rights to the name, and Sowt had already acquired a modest following on Facebook.)

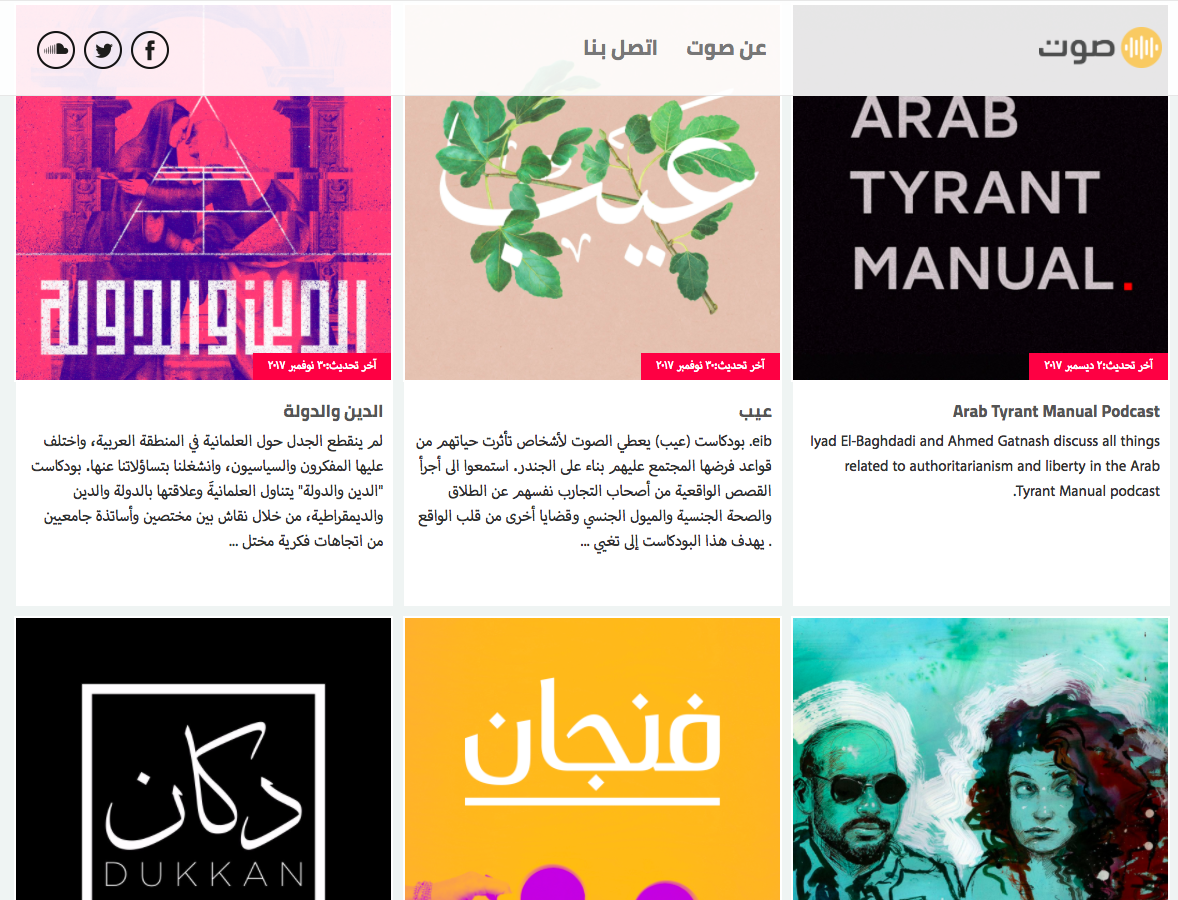

Sowt is distinct in the MENA region for the subject matter its podcasts are willing to traverse. Its original podcasts focus on social issues, such as religion and the state or gender taboos, that are of interest to Arab youth. It has simple immediate targets: to grow its audience, and to grow revenues.

Its shows include Blank Maps, which tackles statelessness in the Arab world and in particular the issue of Palestine, and Eib, which discusses gender taboos. In addition to its own original shows, Sowt also makes audio stories that private clients like UNDP and Médicins Sans Frontieres commission, which provides the company another source of revenue. (Sowt also produces only digital audio, in contrast to traditional Arab radio, which has been slower to respond to the digital age.)

The Sowt network averages a modest 2,000 listens per original podcast episode. The team is happy with these early numbers, having launched its first show in October 2016, and is confident there’s plenty of room for growth.

“Podcasts here will never generate the same amount of interest and revenues as video, but there is some good content that needs to be put together and highlighted to help people rediscover audio storytelling in Arabic, which I hope we’re helping to do,” Tesdell said. “Our primary goal is to produce and curate original Arabic content rather than just translating and adapting U.S. products that might not work for an audience born and bred in the Middle East.”

49 percent of Jordanians across all age ranges listen to radio in Arabic, and just 1 percent listen to it in English, according to the 2017 media use in the Middle East survey from Northwestern University in Qatar, suggesting a need for more Arabic-language audio content. Increasing access to cheaper technologies, a massive shift towards mobile, and the opportunity to multitask while listening to something enjoyable, are other factors that may help spark a podcast listening boom in the region.The Middle East has only just begun to figure out the podcasting market, but “there’s already some good content out there,” Zureiqat said. There’s also increasing interest in the industry from journalists, he said. But in general, audio content has been scattered online without one consistent source for interested listeners to discover new shows. High-touch podcasts are expensive and time-consuming to create, and funding can be hard to come by.

“There are dozens of Arabic shows from the region, but very few are consistent and fewer are of good quality,” said Tala Elissa, a Palestinian-Jordanian producer with Sowt. “We focus a lot on the framework and theoretical buildup of each show and do not compromise on sound quality. We also focus on storytelling, which is almost non-existent in other Arabic shows.”

There are a couple of other MENA-region narrative audio shows that rely on scripts and storylines, but they are mainly released in English. There’s no comprehensive directory of all MENA podcasts, but English-language UAE-based podcasting brand Kerning Cultures has been collecting its own data to map the landscape.

Kerning Cultures counts about 75 active podcasts in the region, including both Arabic and English-language podcasts. Only about five of those are in radio documentary or narrative form, Kerning Cultures cofounder Hebah Fisher said. Most are talk-show style, although she said she believes more longform, documentary-style podcasts will help accelerate interest in podcasting in the MENA market.

Sowt itself has been struggling to find a sustainable business model outside of the grants it’s received so far from the International Media Support and the European Endowment for Democracy. Currently, about 85 percent of Sowt’s funding comes from grants, but it’s aiming to lower that to 65 percent in 2018.

It doesn’t currently rely on in-show advertising, and considers ads completely out of the question down the line as well: “I don’t think ads represent a sustainable approach, especially for small companies and the current Middle Eastern environment,” Tesdell told me.Sowt will likely look to audience memberships and subscriptions, though audience revenue isn’t the organization’s top priority. The team predicts it won’t implement any membership program until the end of 2018, but Tesdell said he thinks Arab podcasts have a small but sufficiently well-off and engaged audience that making money from listeners is possible.