On platforms like Snapchat and Instagram, Stories are cute — they’re perfectly designed for your phone’s screen, they can feel more narrative than disconnected posts, you can be pithy while still including more information than a regular post, and you can communicate more directly with your audience. But they also have drawbacks: the public can’t really see them after 24 hours, and they’re accessible only by users of those apps.

Editor’s note: Hey, sorry to interrupt, Christine, but an important style point first. We’re still not sure what to call this booming format — an annotated mix of photos and videos, arranged in time order, vertically formatted, designed for mobile, navigated via tap, often (though not always!) meant to disappear after a certain period of time.

Snapchat Stories was the important innovator here, and other platforms have generally followed the [Platform Name] Stories motif. But calling the overall format “stories” leads to nothing but confusion in stories (ahem) like this one, since that’s a word already stuffed with meanings. And using the capitalized “Stories,” as our friends at Digiday do, seems to corporatize the format too much, not to mention go against the general precept that common nouns shouldn’t be capitalized.

We asked for suggestions on Twitter and among the nominees were “visual stories,” “card stories,” “mobile slideshows,” “swipeyshows,” “snapettes,” “storycards,” and “a waste of time,” none of which feel perfectly satisfying. So for the remainder of this story (ugh), we’re going to call these “Stories” — but we’re still looking, and if you’ve got a better idea, leave a comment or tweet at us.

Now back to Christine.

Ahem, where was I?

So is there a way to bring the visual components and engaging aspects of Stories on platforms outside of an app? And can you make it a worthwhile channel for reporting news? A group of publishers, including The Washington Post, Wired, Vox Media, and CNN, have been experimenting with a Google-backed framework that tries to do just that. (It first emerged in October as the “Stamp” project, but the framework officially launched this month as AMP Stories.)

“We see it as a new tool in our toolbox for when there are stories with highly visual elements that we can tell in this manner,”

Dave Merrell, the Post’s lead product manager, told me, adding that it’s only deployed on stories where it would “enhance the storytelling” and act as more than just a photo slideshow with text.

“The platforms all have a specific vibe, with Snapchat and Instagram Stories, but because AMP Stories are on the web…there isn’t an overall vibe we’re trying to match,” he said.

Since Snapchat introduced the Stories concept in 2013, users have been communicating by tapping through seconds of visual-plus-big-text; the format has done nothing but grow. Facebook tried to capture their value — if not by ownership then by mimicry — on Instagram and Facebook. And many publishers have been testing the waters across platforms. (Some news apps, like the Yahoo News Digest, also had similar characteristics.) But that’s the thing: These experiences are very much platform-bound. Users can export social stories in some cases, but each platform’s specific mix of fonts and features can make the copying obvious.

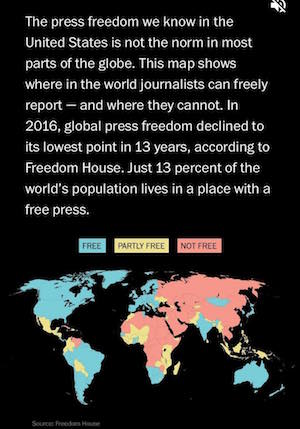

Google, a platform without its own version of Stories, worked with these different publishers to create AMP Stories over the past year, basing some of the code and ideas on its AMP Project for quick-loading mobile content (which has recently expanded to content sent in emails as well). They open-sourced the material so anyone can build a Story and host it on any website, and Google said it will “expand the ways they appear in Google Search.” (The Verge, part of Vox Media which also tested AMP Stories, reported that Google provided some funding for publishers piloting AMP Stories, but Merrell wouldn’t comment on that. And note that there are lots of technologists who think AMP is a bad idea for the web, allowing Google to improperly favor content formatted via what is realistically still a Google-controlled technology, capturing much of the open web into a proprietary format.)So what does an AMP Story look like? If you scroll down on washingtonpost.com on your phone under “More Top Stories,” you’ll see a collection of “Visual Stories” that includes photo galleries, graphics, and now, the AMP Stories labeled as “Visual Story” — that’s what the Post is calling them. If you choose the story “Journalism is a risky business,” the front page of a 16-slide story by former Nieman Fellow Jason Rezaian fills up your screen. (Merrell told me they will be labeling content to distinguish opinion from news articles, etc., but I didn’t see labeling either way on this item.) As with other social Stories, there are tiles to tap through at your own pace. They progressively take you through the story, from Rezaian setting the context in a video segment to maps of global press freedom to photo/text depictions of other journalists imprisoned around the world. The setup isn’t wildly different from social stories on the platforms except this one keeps you on the Post site in your browser and if you try to scroll the site will gently remind you how to navigate by tapping the right side to go forward, the left to backtrack. At the end, a prompt to share this story appears along with three links for further reading on the topic.

Since AMP Stories launched earlier this month, the Post has published items across verticals and story timeliness. One of the Stories with the highest engagement is a step-by-step explanation of how to make cold brew coffee (Merrell notes the East Coast was experiencing unseasonably warm weather when that one was posted), but they’ve also done AMP Stories on what Rohingya refugees left behind, an Olympics 101 on curling, the week in editorial cartoons, and a timeline of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida, with video from students locked down in the classrooms.

“We storyboard it out,” Merrell said. “How many slides do we need, what purpose do each of these slides serve, how many do we need, are these the right order.” The production team, which includes editors, designers, developers, videographers, and photo editors, works with other members of the newsroom to identify AMP Story contenders. Once stories are identified, Merrell said, “the actual technical production of this is not a problem.”

The Washington Post still maintains a presence on Snapchat Discover and regularly posts Snapchat Stories and Instagram Stories. (The topics on Friday afternoon happened to be similarly somber: un-investigated rape kits with a link to a Post story on Instagram, and an analysis of mass shootings and Second Amendment rights leading the Post’s section on Snapchat Discover). Typical publisher items on Snapchat (whether Stories, Discover, or shows) started out as energetic, fast-paced, and highly engaging. Social stories on Snapchat and Instagram can include a link on an individual tile, but an AMP Story can be found by readers on a homepage, shared on other social media platforms, or even distributed via email — and publishers don’t have to play by the platforms’ rules. With Snapchat’s redesign drawing hefty criticism from users (though other platforms have also seen resistance to initial redesigns) and Instagram still being Facebook’s turf, it’s not surprising that publishers are considering their options.

When I asked how much the independence from platforms plays a role in the Post focusing on AMP Stories, Merrell said it is “hugely important to us…The Snapchat team we have here does a great job of a wide variety of stories on Snapchat, and we saw that we had the chops to tell the stories in a visual manner,” he noted. “We’re excited about the engagement there and we also know that the web is a huge platform for us.”

At the same time, Snapchat and Instagram users have come to expect Stories on those platforms, versus readers of washingtonpost.com who might be taken aback by the sudden change in format when clicking on an AMP Story link. “This is such a new user experience shift on the web for people that we’re not really sure what to expect,” he said. “The overwhelming response [in pre-launch user testing] was, ‘This is great, but we would like to know what we’re getting into before we click the link.'” He added that their goal is for readers to get to the end of a Story, and that they have been testing different topics and lengths of Stories.

Okay, but Google isn’t exactly a mom-and-pop shop itself. Is this really independence? Though news organizations have generally rated Google as more cooperative than other tech companies — and Google Search has been bringing more traffic to their sites than Facebook in recent months — would the Post have built out these Stories even without a Google boost? There’s no between-slides advertising in the Post’s AMP Stories (yet), and a Post spokesperson confirmed that Stories currently sit outside the Post’s paywall “at this time.”

“If Google ends up sending us a ton of traffic to these, we wouldn’t turn it down, but we really see this format as a way to engage our current readers as well,” Merrell said. “We don’t see AMP Stories as a fun side project. We believe it will become a core part of our toolbox.”