Americans are fractured over the role of journalists, confused by terms like “op-ed,” and wary of the “watchdog” part of journalism, a new report suggests. Yet they’re also increasingly trustful of their favorite news outlets.

A report out Tuesday from the Media Insight Project, surveying 2,019 adult members of the American public and 1,127 American journalists, suggests a somewhat jumbled and confusing situation. It’s most enlightening when it drills down into how specific groups are thinking about the media in general and about their own favored news sources.

For example:

What do Americans think about the direction of the news industry? A majority, 56 percent, say it is headed in the wrong direction; 42 percent say the right direction.

Views about the direction of the media correspond with trust. While 73 percent of those who trust the news media generally say the media is headed in the right direction, 92 percent of those who say it is untrustworthy think the media is headed in the wrong direction.

Journalists also view the media’s direction more negatively than positively. Sixty-one percent say that the news industry is headed in the wrong direction.

But “the media” is a massively broad category, as the report’s authors note:

In a fragmented media landscape, the notion of a mass media that everyone consumes together — as in the era of the three nightly newscasts nationally or a singular newspaper in every city — no longer captures the reality of how news is consumed. The questions about media trust inevitably are asking people to describe an attitude toward publications they do not use.

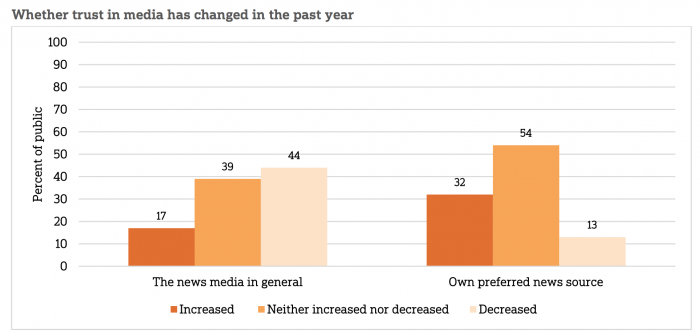

To avoid that problem, the survey asked people to name a publication or outlet they rely on heavily. When we look at the data this way, we get a quite different picture.

Some other findings from the report:

— Republicans are more likely to say that the media covers various groups inaccurately:

Republicans are much more likely than others to think the press inaccurately covers men (34 percent vs. 16 percent of Democrats and 25 percent of independents). Republicans (29 percent) are also somewhat more likely than Democrats (22 percent) to say news coverage of women is slightly or not at all accurate. Further, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say the coverage of the wealthy is inaccurate.

Republicans are also much more likely to say the press does not accurately cover Republicans and conservatives. Majorities of Republicans say conservatives (53 percent) and their own party (51 percent) are portrayed inaccurately. Republicans are also the most likely to say that Democrats are not accurately portrayed — over a third (35 percent) say the media covers this group inaccurately — more than twice the proportion of Democrats who say so (15 percent). These opinions among Republicans warrant further assessment to reconnect with this audience.

Interestingly, partisanship does not affect opinions about coverage of some other groups. For instance, there are no partisan differences when it comes to perceptions of the poor. Nearly half of both Republicans (48 percent) and Democrats (47 percent) consider coverage of lower-income people slightly or not at all accurate. And while there are differences in how partisans’ perceive coverage of rural Americans and grassroots political movements, those gaps are statistically driven by demographics and other variables more than partisanship.

For some of these, support of President Trump is a dividing line. Americans who approve of Trump are more than twice as likely as those who disapprove to say the media’s portrayal of Republicans is inaccurate. Fully 47 percent of Trump supporters think the GOP is inaccurately portrayed, while the number is 22 percent among those who don’t support Trump.

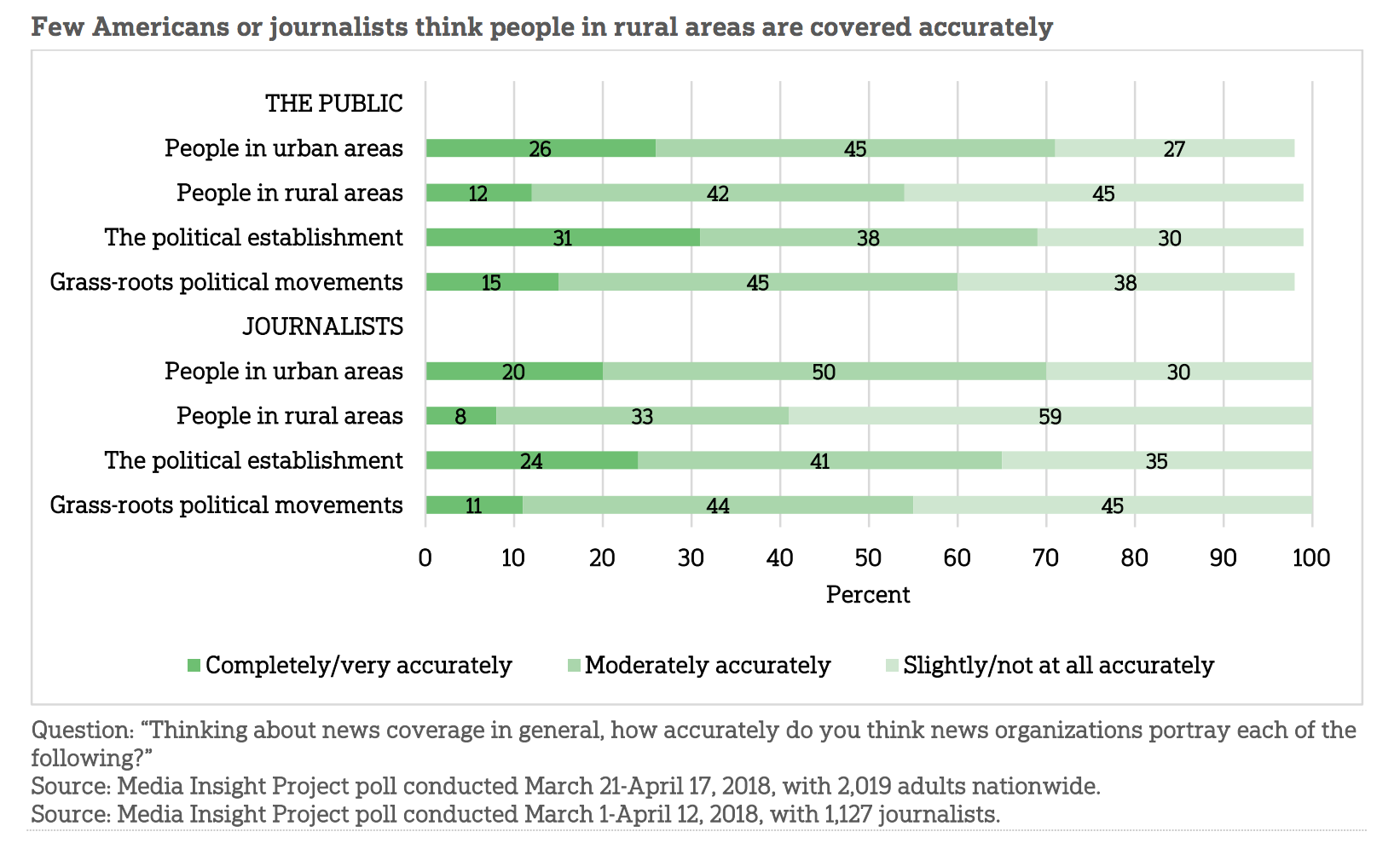

— Rural disadvantage. Both the American public and journalists believe that people who live in rural areas are not covered accurately.

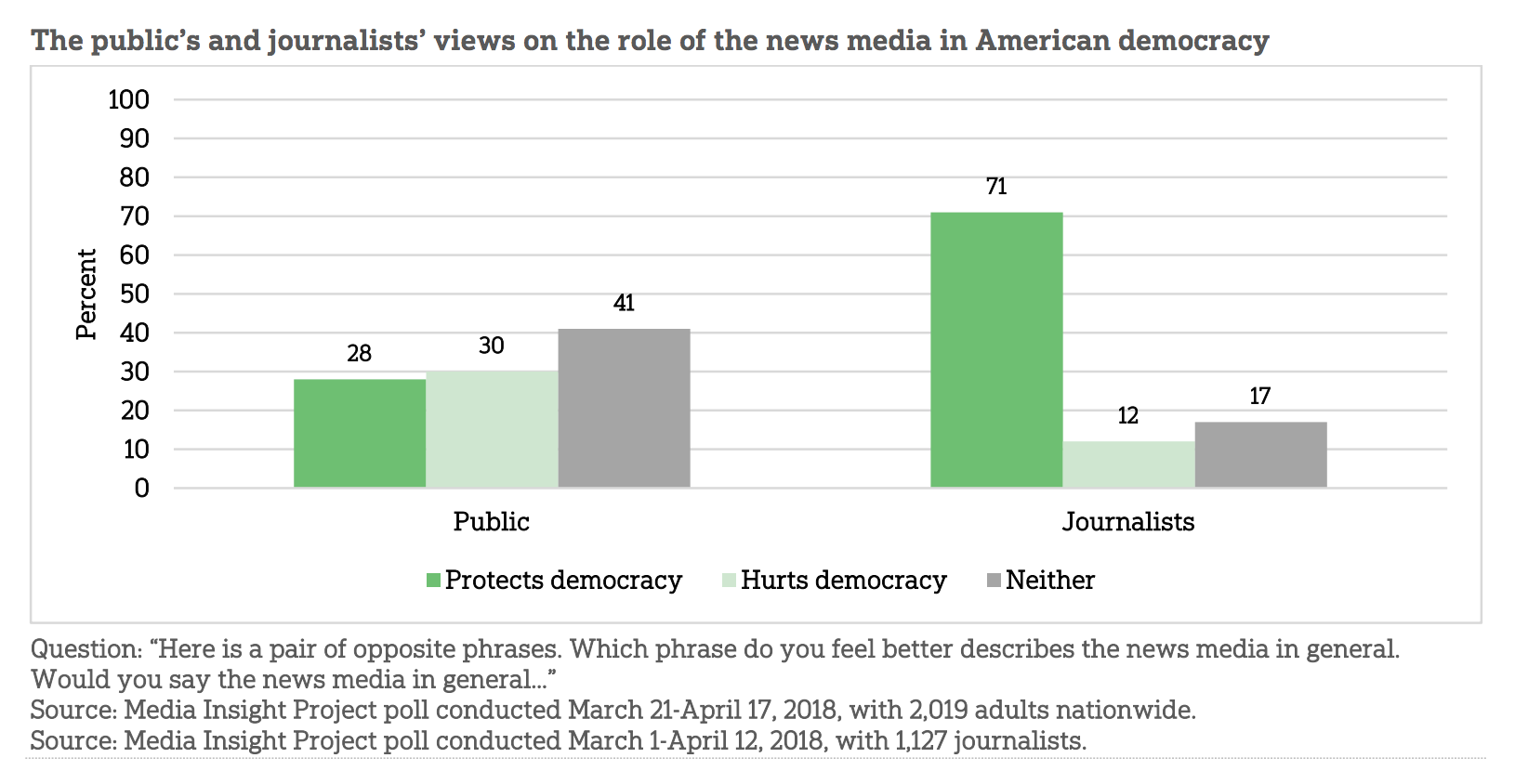

— “Democracy dies in darkness?” Well… The American public and journalists themselves differ hugely in whether they believe that journalism protects democracy. This was one of the largest differences in opinion between the two groups that NORC found. (NORC also asked this question last year; between last year and now, there was “a 6 percentage point drop in the proportion saying the media protects democracy, and a 6 percentage point increase in the proportion saying it neither protects nor hurts.”

— 29 percent of Americans subscribe to a print or digital newspaper, according to this report. “These subscribers tend to have more positive views than non-subscribers on many components of the press, including journalists as a group (51 percent vs. 37 percent), news organizations in general (48 percent vs. 32 percent), public radio (56 percent vs. 37 percent), PBS (62 percent vs. 49 percent), and individual journalists they follow (55 percent vs. 38 percent).”

— Young people are the least likely group to trust the accuracy of news media — even the accuracy of their preferred media sources.

While a majority of adults age 45 and older (52 percent) call the news media trustworthy, only about a third of those under age 45 (35 percent) agree. Adults age 45 and older even trust their preferred news sources more than do younger adults (80 percent vs. 66 percent).

Moreover, the youngest Americans are the only age cohort in our survey that says most news reports are fairly inaccurate. A majority of adults age 29 and younger say most news reports are fairly inaccurate (53 percent). A majority of those age 30-44 (57 percent), age 45-59 (61 percent), and age 60 or older (67 percent) say most news reports are fairly accurate.

— A sprawling definition of fake news. Old and young Americans — and Trump supporters — also have different opinions about what fake news is. But one thing is clear: “Those who wanted to expand the definition of fake news, to give it multiple meanings and less precision, have prevailed.”

Here, for instance, is how Trump supporters and opponents define fake news.

Here are the differences by age:

Older adults tend to have a broader definition of what constitutes fake news than do younger adults, especially when it comes to conspiracy theories and unsubstantiated rumors. Seventy-three percent of adults age 60 or older and 68 percent of adults age 45-59 say an outlet passing along conspiracy theories is fake news, compared with 57 percent of those age 30-44 and 51 percent of those age 18-29 who say the same.

Likewise, 52 percent of the oldest adults say news stories that are unfair or sloppy are fake news, compared with 33 percent of the youngest adults.

— Should journalists act as watchdogs? Answers to this vary hugely based on who you are. “The most striking difference between public expectations of the press and journalists’ expectations came on the watchdog role: While just over half of the public considers it extremely/very important, fully 93 percent of journalists rank it so.”

This question shook out along partisan lines:

Sixty four percent of Democrats say the watchdog role is extremely/very important, compared to 50 percent of Republicans and 39 percent of independents. In terms of age, adults age 45 and older (61 percent) are more likely than adults under age 45 (45 percent) to think the watchdog role is important. And whites (58 percent) are more likely than blacks (42 percent) and Hispanics (46 percent) to say this is important. Finally, education is also a differentiator, with a divide between those with no college (48 percent) and college (66 percent).

The Media Insight Project is a joint initiative of the American Press Institute and The Associated Press–NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. The full report is here.