The newspaper tariffs are dead. How big a difference will that make to those whose businesses still depends on dead trees?

On Wednesday, the International Trade Commission —like numerous judicial or regulatory bodies before it in the Trump era — reversed the tariffs that the Commerce Department had placed on Canadian newsprint.The unanimous 5-0 decision surprised many, even though the ill-considered tariffs were silly, ignoring the actual way the newsprint trade has long been structured. The whole effort symbolized the times: a private equity company, recently buying into an established industry, looking for a quick buck, and using the politicized trade environment to do it. Even as the tariffs go away, it’s essential to understand that they represent only a small part of the problem that daily newspaper publishers now face. Though that black swan of tariff doom has flown away — an appeal of the decision by NORPAC, which brought the case, is possible, but seems unlikely — other troublesome threats remain aloft.

First, even in terms of the price of newsprint, the elimination of the tariffs provides only partial immediate relief.

Significantly, the recent rise in newsprint pricing of about 30 percent has been driven only partly by the tariffs. In fact, one CEO of a substantial chain told me this week that only a third of the pricing increase could be directly linked to the tariffs. Two-thirds of it, he said, was the “premium pricing” most of the newsprint producers added on to the tariffs. Why? Because they could, tucking in the price increases along with real tariff-induced pass-along pricing. Publishers and newsprint producers long have played a cat-and-mouse game on pricing, with increases, rollbacks, feints, and the like.

Will the as-much-as-two-thirds increase stick or go away? While the Tom-and-Jerry game is nothing new, the terrain on which it now plays out has been transformed. Publishers use maybe a third of the newsprint they used in the year 2000, according to industry analysts. That means the mills themselves, as suppliers to a receding industry, have consolidated. There are fewer owners, fewer mills, and less supply. Consequently, publishers who might have tried to play three suppliers off against each other in days gone by no longer can.

The bigger picture: As the daily printed newspaper era fades rapidly into history, everything about it is getting tougher.

If the tariffs, and related higher pricing, had stuck, publishers were looking at a 10 percent reduction in EBITDA. That was going to be a big hit, and it had already spurred a spate of staff, section, and day cutbacks (as chronicled here). From Tampa, Florida, to Salisbury, North Carolina, to Natchez, Michigan, to Grand Junction, Colorado,, the list was growing.

Now, as the News Media Alliance, which built a coalition of hundreds of organizations to oppose the tariffs, put it on Wednesday: “The tariffs have disrupted the newsprint market, increasing newsprint costs by nearly 30 percent and forcing many newspapers to reduce their print distribution and cut staff. We hope today’s reversal of these newsprint tariffs will restore stability to the market and that publishers will see a full and quick recovery.”

Were it so.

In truth, the print newspaper industry is plummeting southward at a faster and faster rate. Consider, in aggregate and individually, the financial results of the just-reported second-quarter, and see that the tariff relief just removes one boot from the neck of an industry writhing in pain.

These four charts on Q2 overall revenues from four top publicly traded daily newspaper companies display starkly how poorly all the chains are doing in the strongest economy in a decade. For each, I’ve pulled out “same store” revenues, meaning that the impact of acquisitions made or properties sold over the last year are excluded. Not all companies report all the numbers, even in these basic categories. So omissions are noted. Further, what each company includes in each of these categories may differ, usually slightly. Overall, though, these apples-to-apples comparisons are directionally accurate.

Most of the chains find themselves slipping farther and farther from revenue growth. This headline number tells you that digital initiatives simply are not making up for overall print revenue losses.

It’s been about 10 years since these companies grew overall revenue quarter over quarter.

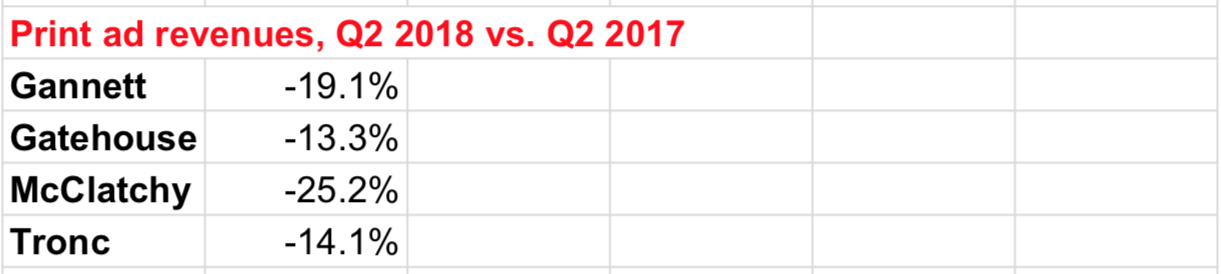

Next, consider their print ad decline.

This is the number that is causing the big overall revenue decline. Print advertising is disappearing rapidly, with huge percentage losses on a base number that has decreased by some 60 percent in 10 years.

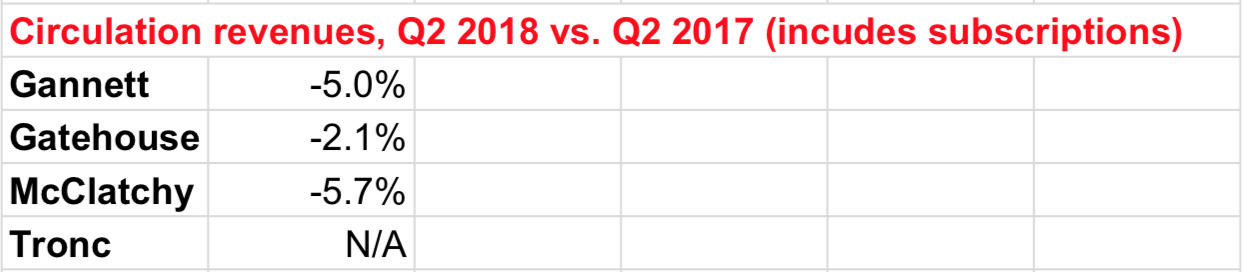

Now look at their circulation revenue decline:

Long ago, newspaper companies hoped that digital ad revenues would make up for print ad losses, a phenomenon that never occurred consistently. Over the past couple of years — owing to The New York Times’ innovation in digital subscription and reader revenue — circulation revenue gains were supposed to make up for ad (mainly print ad) losses.

Between 2015 and 2017, a number of daily newspaper chains were able to report positive circulation revenue quarter over quarter. The combination of higher print pricing and the growing digital subscriptions produced that positive number. But now they have hit a wall and gone negative. Volume loss in print circulation is accelerating; digital subscription momentum has been hard to maintain.

One current phenomenon: As publishers cut back on newsprint, cutting sections and pages, they worsened their value proposition with their best and most loyal, high-paying customers: their print subscribers. Even subscribers who were loyal for decades are cancelling.

Make no mistake: All these publishers are growing digital revenues. I can’t break out good comparative numbers because publishers report those revenues in non-standard buckets, making easy comparison impossible. But digital revenues are less and less able to make up for lost print revenues, both ad and subscription.

McClatchy’s Craig Forman sums up the journey against time he and his fellow CEOs are on. The big idea is to reduce the percentage of revenue dependent on the slowly dying revenue stream of print advertising, the slowly dying revenue stream.

Forman said on McClatchy’s earnings call, “Revenues exclusive of print newspaper advertising accounted for 80.4 percent of total revenues in the second quarter of 2018, an increase from 74.7 percent in the second quarter of 2017.”

That number is moving in the right direction at McClatchy and elsewhere, but the dependence on print revenues — both print ads and, less so, print subscribers — clouds the 2020s future.

And so we have expense cuts, which will only deepen in 2019. Newspaper companies have been cutting expenses literally for a decade, and it’s not clear how much more there is to cut.