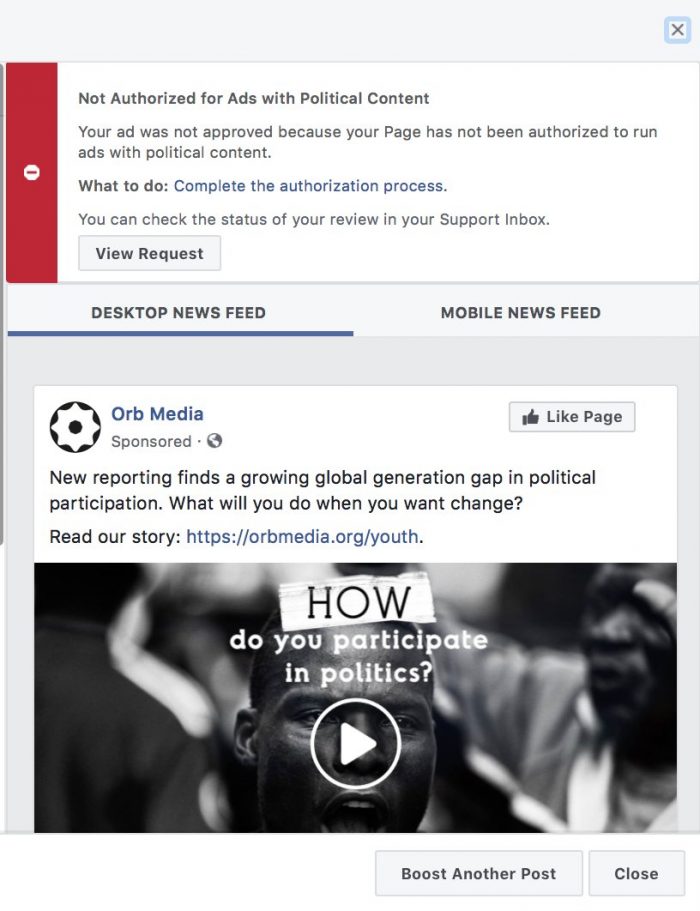

It happened again: A news organization tried to pay Facebook to promote its journalism — which included reporting on politics — and Facebook said no, declaring it “political content” the news organization wasn’t authorized to push.

Last night, an attempt to promote our recent story was blocked by @Facebook's algorithm. This newsworthy piece of impartial and well-documented #reporting about #politics was confused with political content. /1 pic.twitter.com/Q0HjqMwIN8

— Orb Media (@OrbTweet) September 6, 2018

We know that Facebook is a private platform, and we understand that Facebook is trying to prevent misinformation campaigns. However, we have newsworthy, impartial journalism that is being blocked from further dissemination due to an act of #censorship. /3

— Orb Media (@OrbTweet) September 6, 2018

The piece in question? “Generation activist: Young people choose protest over traditional politics.”

#GenerationActivist (https://t.co/AmqgoU2AO8) reports a growing global gap in political participation based on nearly a million data points in 128 countries. By blocking the post's promotion, Facebook Ads hindered our launch & hurt both our business and public service purpose. /2

— Orb Media (@OrbTweet) September 6, 2018

“Any human being that would put an eye on it would be able to say this is not political propaganda. This is really fair and well-documented journalism. It should not be confused,” said Naja Nielsen, the chief journalism officer of Orb Media, a nonprofit journalism organization that works with local and regional publishers to share stories of global importance. “The problem of course is that these platforms are so important in the ways we get information, and if the algorithms are not good enough to show the difference between propaganda and a piece of well-made journalism, then we as a community have problems.”

(Nielsen said Facebook’s algorithm has also rejected this photo of a boy walking through mountains of plastic waste in the Philippines. Perhaps most famously, Facebook blocked, and then relented on, a newspaper’s posting of the Pulitzer-winning Vietnam War napalm girl photo in 2016, though that was for alleged sexual content rather than politics.)

Facebook says that the Orb article would be fine to be promoted — but only if Orb first registers as a political advertiser through its system, which can take 10 days. (They snail mail a secret code to your home to confirm you’re on U.S. soil.) Still facing criticism for its role in Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. elections, Facebook’s position has shifted toward “better safe than sorry” with a blanket registration ask to anyone wanting to promote content dealing with certain national issues.

Orb Media is not the only publisher to have its attempt to advertise blocked by Facebook’s system interpreting it as political content (the additional registration, you know, comes after that whole U.S. presidential election thing.) Earlier this summer, ProPublica reported how The Hechinger Report, Voices of Monterey Bay, BirminghamWatch, and other publishers had had certain stories blocked by Facebook’s advertising filter, while other truly political content slipped through. Facebook said it would work on it — but it keeps happening.

Hi there, @facebook. This is not political content. This is journalistic content that deals with policy. There's a difference.

Didn't you go over this with @ProPublica recently? https://t.co/kMCOzWanAY pic.twitter.com/3mSViK3sdv

— Reveal (@reveal) June 20, 2018

We've had to deal with this too at @statnews. Super frustrating.

— Megha Satyanarayana (@meghas) June 20, 2018

We recently went through this @topicstories / @firstlookmedia. An account admin has to be personally verified first to get the page whitelisted, then each ad is taken on a case by case basis w/r/t to it being 'political' or not.

— Man Bartlett (@man) June 20, 2018

Facebook has tried to make some amends, creating a separate news archive from the political archive. But news organizations’ representatives are still required to register through the authentication process involving submitting a home address and photo ID if the organization wants to run ads related to 20 specific national issues like “values,” “immigration,” or “abortion.” Over the past few months, Facebook has also introduced the ad archive API (admission by application only).

We reached out to Facebook for comment on the Orb case, and a spokesperson directed us to this summer blog post by Facebook’s news partnerships head Campbell Brown. “We don’t want to be in a position where a bad actor obfuscates its identity by claiming to be a news publisher, and what’s more, we know there can be editorial content from news organizations that takes political positions. For these reasons, we’re focused on the separate archive treatment, without exemptions,” she wrote.

The one thing that — mostly — everyone can agree on is that it’s important for Facebook to have these filters, but it’s also important to get them right.

Orb publishes six investigations a year and coordinates heavily with publishing partners from dozens of countries to push the stories at the same to drive dialogue. “Timing is everything. When it’s been more than 24 hours that our story is on our partners’ sites and we’re held back from promoting it, that is not good for a small business like ours,” Nielsen said.

Some outlets, like New York Magazine, stopped buying ads for particular articles that could be misconstrued by Facebook as political content. Some have stopped buying Facebook ads altogether.

“Like many other newsrooms, we opted to not hand over anyone’s personal information to Facebook — even if it meant being able to run ads that contain content the company deems ‘political’ based on its listed criteria. As a result, our ability to boost this sort of content remains limited,” Reveal’s engagement reporter Byard Duncan said.

Nielsen said Orb would have to think about paying Facebook to promote articles again. But when you’re trying to have a global impact, it kind of helps to make sure you’re putting it in the line of sight of people who care.

“I completely acknowledge that Facebook is a private company. They have the rules they want to have. We as users have to listen to whatever decisions they’re making,” Nielsen said. “But, as we all know, in the age of the internet publishing an article is not the same as the article being seen by people interested in it.”