The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

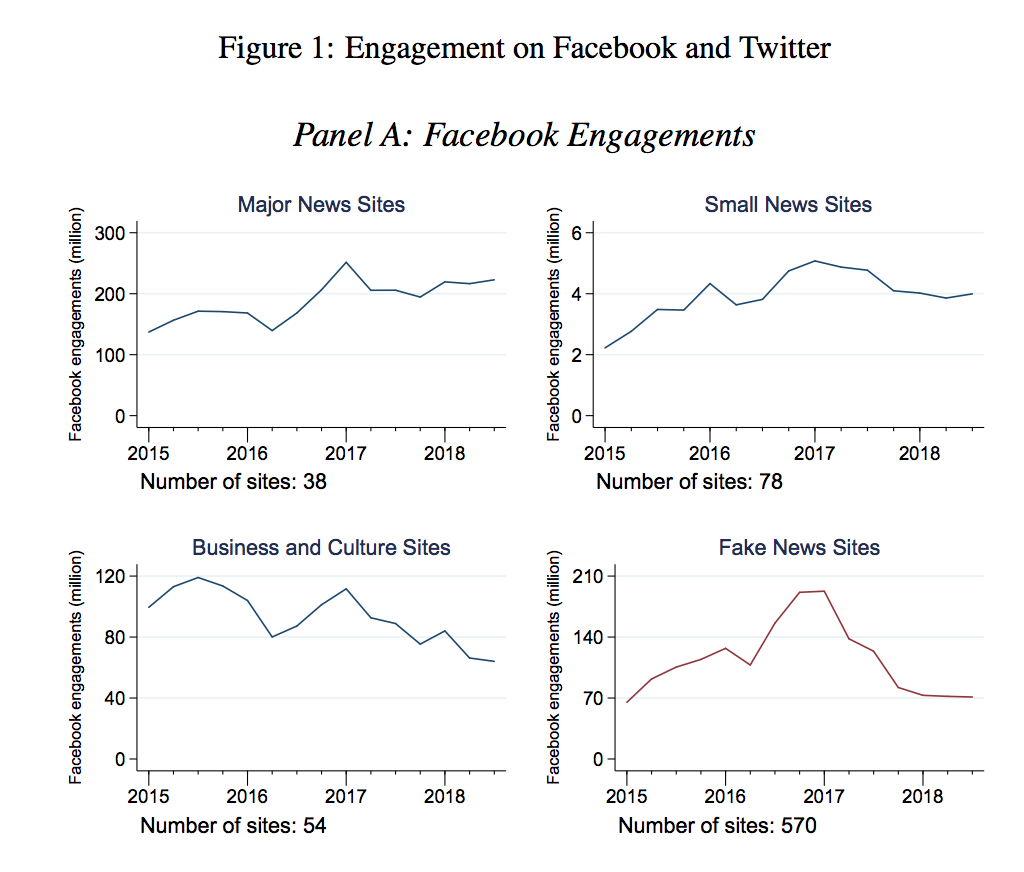

“The overall magnitude of the misinformation problem may have declined.” It’s fun to hate on Facebook, but credit where credit’s due: The platform’s attempts to get fake news and misinformation out of people’s feeds seem to be working, according to a new working paper from NYU’s Hunt Allcott and Stanford’s Matthew Gentzkow and Chuan Yu. Looking at the spread of stories from 570 fake news sites (the list, here, includes sites that publish 100 percent fake news and sites that publish some pure fake news along with other highly partisan/misleading stories), and using BuzzSumo to track monthly interactions (shares/comments/reactions/likes/tweets), they find that “the overall magnitude of the misinformation problem may have declined, at least temporarily, and that efforts by Facebook following the 2016 election to limit the diffusion of misinformation may have had a meaningful response.”

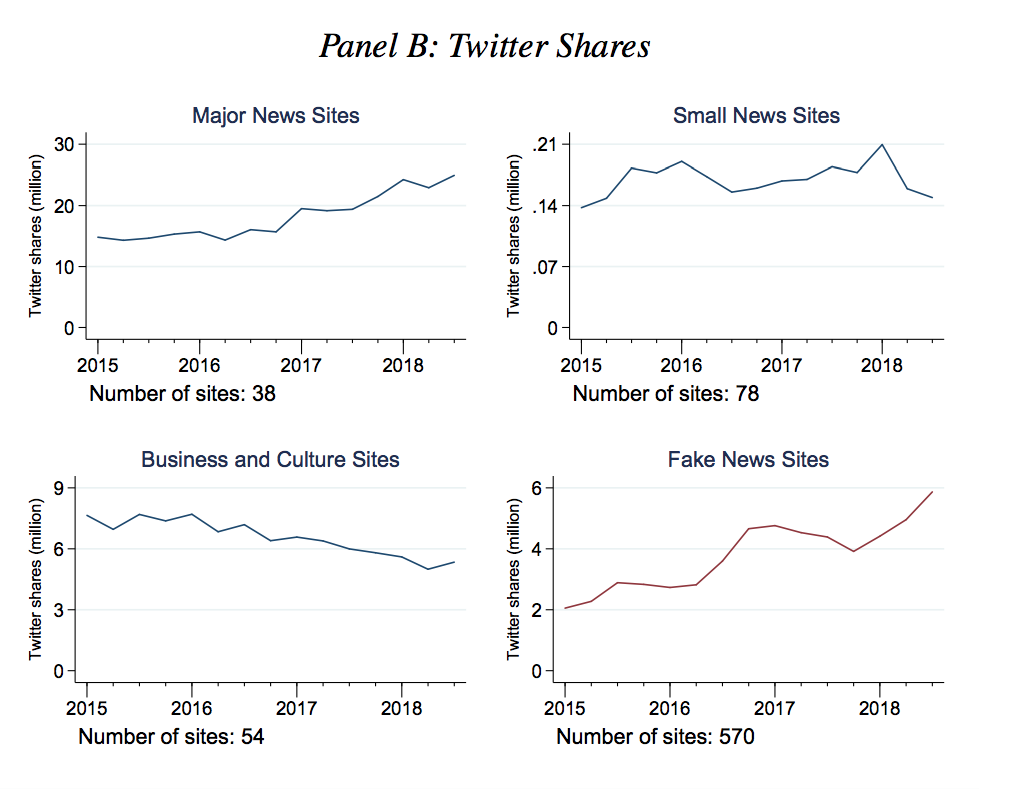

Engagements with fake sites on Twitter, meanwhile, have continued to rise, though Twitter remains much smaller than Facebook.

The researchers also compared the spread of stories from fake sites to the spread of stories from legitimate sites and found that those interactions have been “relatively stable over time” — suggesting further that it’s the fake news sites, in particular, that are being affected.

“Fake news interactions increased steadily on both platforms from the beginning of 2015 up to the 2016 election,” the researchers write. “Following the election, however, Facebook engagements fell sharply (declining by more than 50 percent), while shares on Twitter continue to increase.”

One thing to be super clear about: Facebook is way bigger than Twitter and there is still a ton of fake news there — and much more, in sheer numbers, than there is on Twitter.

The absolute quantity of fake news interactions on both platforms remains large…Facebook in particular has played an outsized role in its diffusion. Figure 1 shows that Facebook engagements fell from a peak of roughly 200 million per month at the end of 2016 to roughly 70 million per month at the end of our sample period. As a point of comparison, the 38 major news sites in the top left panel — including The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, CNN, Fox News, etc. — typically garner about 200-250 million Facebook engagements per month. On Twitter, fake news shares have been in the 4-6 million per month range since the end of 2016, compared to roughly 20 million per month for the major news sites.

It surprised me that if you imagine a giant pool of, say, 280 million monthly Facebook engagements, a quarter of those are coming from sites that publish at least some fake news. “I agree it’s kind of amazing,” Stanford’s Gentzkow told me in an email. “One important note is that the fake news number is engagements with those sites, not engagements with false stories. The list of 570 includes sites that have been flagged as producing some misinformation, but my impression is that a large share of content on those sites is not false per se (though it may be highly partisan, misleading, etc.)

“It’s also important to note that engagements are not the same thing as exposure. I suspect these highly partisan stories generate more engagements per view than say ‘Stocks hit records as investors set aside trade fears’ (the current top story on WSJ.com).”

Still, “the fact that Facebook engagements and Twitter shares follow similar trends prior to late 2016 and for the non-fake-news sites in our data, but diverge sharply for fake news following the election, suggests that some factor has slowed the relative diffusion of misinformation on Facebook,” the researchers write. “The suite of policy and algorithm changes made by Facebook following the election seems like a plausible candidate.”

Facebook spokesperson Lauren Svensson also noted to Slate’s Will Oremus:

The study looked at engagement on all articles from a given website, whereas Facebook has focused much of its effort on limiting specific stories that its users or third-party fact-checkers have flagged as false. In other words, Facebook isn’t trying to throttle all the content from the sites examined in the study, so we shouldn’t expect their content to disappear from the news feed.

For its part, a Twitter rep told Slate that it doesn’t want to be an “arbiter of truth.”

“Choosing what to amplify is not the same as curtailing someone’s ability to speak.” Here’s the text of a keynote that danah boyd, founder of research institute Data & Society, gave at ONA last week. Mainstream journalists are getting played, boyd says.

Media manipulators have developed a strategy with three parts that rely on how the current media ecosystem is structured:

1. Create spectacle, using social media to get news media coverage.

2. Frame the spectacle through phrases that drive new audiences to find your frames through search engines.

3. Become a ‘digital martyr’ to help radicalize others.

The concept of “crisis actors” is a good example of this.

Manipulators aren’t trying to get journalists to say that witnesses to gun violence and terrorism are actually crisis actors. Their goal is to get the news media to negate that frame — and negate the conspirators who are propagating that frame. This may be counter-intuitive, but when news media negates a conspiratorial frame, the people who are most open to such a conspiracy will want to self-investigate precisely because they don’t trust the news media. As a result, negation enables a boomerang effect.

And, she argues, journalists need to quit it with the “both sides.”

I get that you feel that it’s important to cover “both sides” of a story. But since when is intolerance and hate a legitimate “side”? By focusing on bystanders and those who are victimized by hate, you can tell the story without reinforcing the violence. Extremists have learned how to use irony and slippery rhetoric to mask themselves as conservatives and argue that they are victims. Ignore their attention games and focus your reporting on the wide range of non-hateful political views in this country that aren’t screaming loudly to get your attention. There is no need to give oxygen to fringe groups who acting like the bully in the 3rd-grade classroom. Inform the public without helping extremists recruit. This isn’t about newsworthiness. And it’s unethical to self-justify that others are using the term. Or that people could’ve found this information on social media or search engines. Your business is in amplifying what’s important. So don’t throw in the towel.

A good question from the audience: Does this mean we shouldn’t cover Nazis? Not cover ISIS?@zephoria: There’s a difference between covering ISIS as an important foreign story, and reporting breathlessly on beheading videos, which are a media manipulation tactic. #ONA18

— Gabe Rosenberg (@GabrielJR) September 13, 2018

Read, also, BuzzFeed’s Charlie Warzel‘s thoughts on this. “I’d like to think that, in most cases, the benefit of shining some light on the pro-Trump media’s manipulation tactics outweighed the negatives of attracting attention to that group. But it’s not always so clear.”

How far-right YouTubers spread their beliefs to “young, disillusioned” audiences. In a new report for Data & Society, Rebecca Lewis looks at how “an assortment of scholars, media pundits, and internet celebrities” “adopt the techniques of brand influencers to build audiences and ‘sell’ them on far-right ideology.” The members of this “Alternative Influence Network,” she writes, identify with a variety of groups that can be slippery to identify:

Many identify themselves primarily as libertarians or conservatives. Others self-advertise as white nationalists. Simultaneously, these influencers often connect with one another across ideological lines. At times, influencers collaborate to the point that ideological differences become impossible to take at face value. For example, self-identified conservatives may disavow far-right extremism while also hosting explicit white nationalists on their channels…Many of these YouTubers are less defined by any single ideology than they are by a ‘reactionary’ position: a general opposition to feminism, social justice, or left-wing politics.

Lewis illustrates how, by appearing on one another’s shows, members of the network “create pathways to radicalization.” For example, “conservative pundit Ben Shapiro is connected to white nationalist Richard Spencer through the vlogger and commentator Roaming Millennial; she has appeared on Shapiro’s YouTube show and has hosted Spencer for an extended interview on her channel.” “By connecting to and interacting with one another through YouTube videos,” Lewis writes, “influencers with mainstream audiences lend their credibility to openly white nationalist and other extremist content creators.”

There are two main ways that these influencers “differentiate themselves from mainstream news as a way to appeal to young, disillusioned media consumers,” Lewis writes — first, by stressing their “relatability, their authenticity, and their accountability” to their audiences and second, by providing “a likeminded community for those who feel like social underdogs for their rejection of progressive values.” (Part of this entails “consistently project[ing] the idea that nonprogressives are ‘persecuted against’ because of their beliefs.”) These strategies — being relatable, authentic, accountable! Providing community! — are, of course, also exactly what traditional news organizations are trying to do to appeal to more readers.

Critics like Zeynep Tufekci have written about how YouTube’s recommendation algorithm “can nudge viewers into accessing extremist content through recommended videos.” But “radicalization on YouTube is also a fundamentally social problem,” Lewis writes. “[Even] if YouTube altered or fully removed its content recommendation algorithms, the AIN would still provide a pathway for radicalization.” There are, however, steps YouTube could take in response:

The platform currently provides Silver, Gold, and Diamond awards for content creators who have reached 100,000, 1 million, or 10 million subscribers, respectively. At this point, the platform reviews channels to make sure they do not have copyright strikes and do not violate YouTube’s community guidelines. At these junctures, the platform should not only assess what channels say in their content, but also who they host and what their guests say. In a media environment consisting of networked influencers, YouTube must respond with policies that account for influence and amplification, as well as social networks.

The full report is here.

The New York Times wants your examples of disinformation. The Times put out a call for “examples of online ads, posts and texts that contain political disinformation or false claims and are being deliberately spread on internet platforms to try to influence local, statewide, and federal elections.” There’s a form that readers can use to send in screenshots. The kinds of “social media disinformation” that the Times is looking for include:

— A Facebook account spreading false information about a candidate for office, or impersonating a candidate

— A Twitter post attempting to confuse voters by sharing false information about the election process (for example, by advertising the wrong Election Day, or promoting nonexistent voter ID requirements)

— A YouTube channel or Instagram account that uses doctored or selectively edited videos or images to mislead voters about a candidate or issue

— A disinformation-based smear campaign against a candidate being organized on Reddit or 4Chan, or in a private Facebook group

— A text message with false information to impersonate a candidate or confuse voters