Blocking and muting on Twitter are common ways for users to deal with the less pleasant elements of the medium: trolls who attack, Nazis who incite, misinformation peddlers, and garden-variety jerks. And that’s certainly true of journalists, who come under far more abuse than the media Twitter user.

But is blocking someone who is a respected member of the commentariat — and a frequent source for your news organization — okay if he’s tweeted something critical of you or your work?

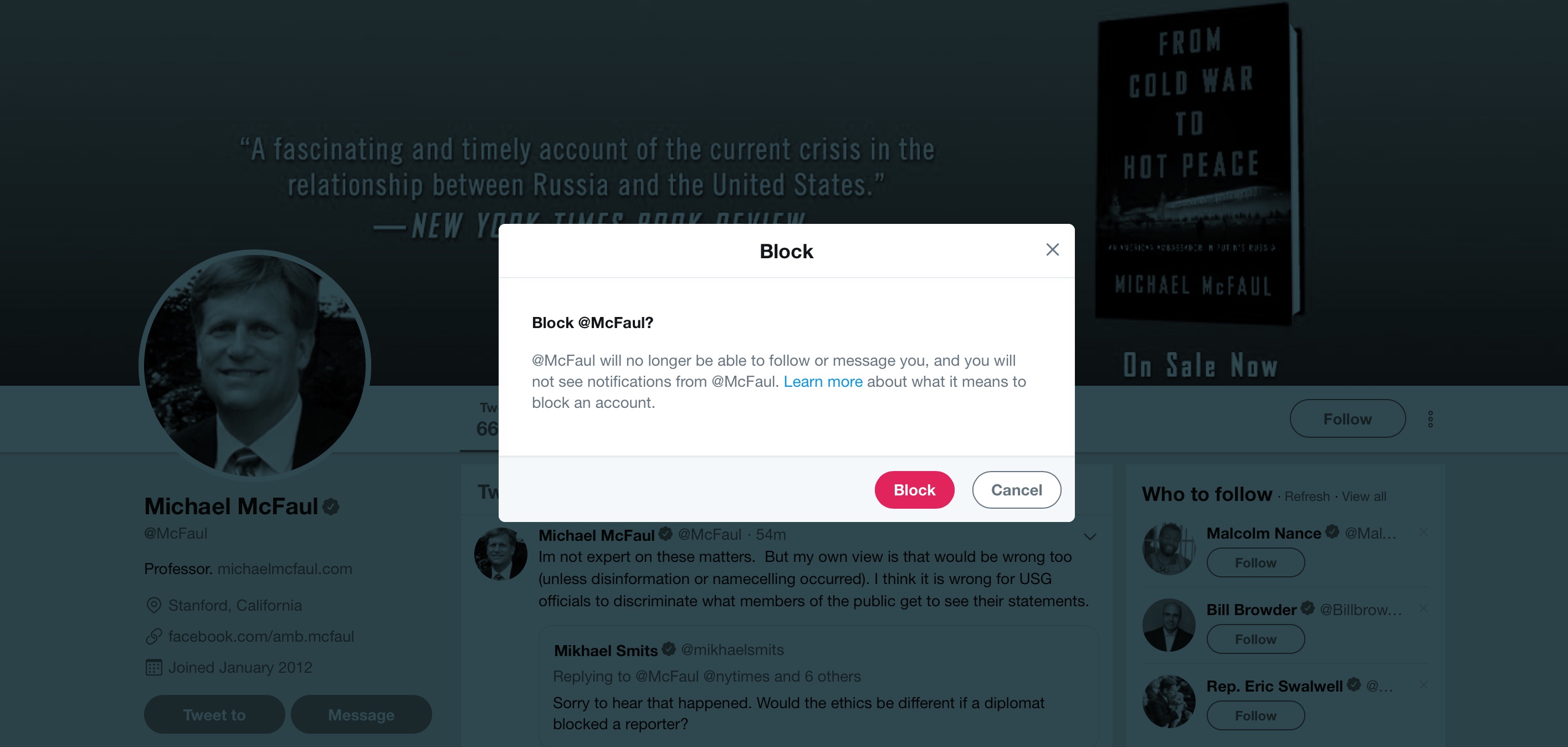

That question popped to mind when I saw this tweet from Michael McFaul. McFaul is a former U.S. ambassador to Russia, Obama administration official, and Rhodes Scholar who has been a professor at Stanford for the past 24 years. Agree or disagree with him (and he certainly has his critics), he’s a serious person; the Times has quoted or mentioned him 16 times in the past year and more than 150 times overall.

Yesterday, he tweeted a criticism of a Times story by Elizabeth Williamson and Ken Vogel in which they interviewed the 78-year-old mother of a former Hillary Clinton advisor, who has since said she didn’t understand she was being interviewed on the record for a story.

This is shocking. @nytimes , what are you doing? What on earth would a mother have to do with a story about her daughter and Sanders? Now more than ever, we need our best news organizations to be their best. This is not that. https://t.co/bab0mRLBFl

— Michael McFaul (@McFaul) April 16, 2019

There are arguments on both sides, and McFaul is by no means alone in his criticism. (Here’s a Washington Post piece on the debate. A Times spokesperson said the story included “accurate, on-the-record comments” by the mother.)

Help me understand the editorial/journalistic decision to interview the mother of one of the 2 people involved in this "dispute"? How is she a legitimate source? Serious question. I'm willing to change my mind. https://t.co/bgNAbQdlsc

— Michael McFaul (@McFaul) April 16, 2019

And I am not making any generalizations about the @nytimes or the authors of that piece. But that PARTICULAR article violated some basic rules of decency regarding reporting. They should admit their mistake, apologize, and move on. No one (and no publication) is perfect. https://t.co/GENpWNEfRe

— Michael McFaul (@McFaul) April 17, 2019

Early this morning, McFaul tweeted that Ken Vogel, one of the two bylines on the piece, had blocked him on Twitter.

I just realized that @kenvogel has blocked me? Because I criticized his article today? Wow. I've worked with dozens, maybe hundreds of reporters @nytimes over decades, including Ken. This is really odd.

— Michael McFaul (@McFaul) April 17, 2019

A @nytimes reporter, @kenvogel, has blocked me on @twitter. 1st time ever. I have interacted with Mr. Vogel in the past, trying to help his reporting. Can someone from @nytimes please justify this behavior? I find it unethical. @peterbakernyt @maggieNYT @SangerNYT @marclacey

— Michael McFaul (@McFaul) April 17, 2019

I find it unethical. Frankly, I'm also shocked. And as a HUGE fan and 30+ year subscriber of the @nyt, I am also saddened and offended. (Imagine me blocking a Stanford student?) https://t.co/UlcGaqaMyX

— Michael McFaul (@McFaul) April 17, 2019

Tweets ensued! Some people thought McFaul should get a grip — he has no inherent right to the attention of a Times reporter, and journalists have the right to shape their Twitter environment as they see fit. If they can decide to follow or not follow someone, can’t they also choose to block or not block?

This is a freakishly entitled viewpoint.

— Chapeaudupape (@Popehat) April 17, 2019

I like @McFaul but it’s an odd claim that either the NYT or Vogel owe him a justification here. Free country, etc. https://t.co/udePlb2fXE

— Niall Stanage (@NiallStanage) April 17, 2019

Being able to interact with/harass/pester or even just bore journalists on Twitter is not a human right

— Allison Morris (@AllisonMorris1) April 17, 2019

But others thought that a reporter blocking a source violates of the openness-to-criticism that should be implicit in being a working journalist. A paying Times subscriber should be able to read a Times reporter’s tweets, given that it’s part of their work product.

Since he's using it as an extension of his 4th estate workspace, yes. If Ken wants to start a clearly personal page and spam us all with cat lulz pics, he can block away.

— My Sweet Baboo Redux (@babsben) April 17, 2019

Don’t think it matters that he mass blocked. I pay for a subscription to @nytimes. As long as I am respectful and don’t violate Twitter rules I should be able to question and criticize journalists tweeting from their official accounts.

— Bridget OBrien (@bridgetobrien06) April 17, 2019

If he's blocking someone like @McFaul, it makes you wonder what other sourcing he's blocking/ignoring based on his own comfort. Bad journalism confirmed.

— Alex (@didgerifree) April 17, 2019

The to-block-or-not-to-block debate has hit the courts recently in another form: a lawsuit filed by Columbia’s Knight First Amendment Institute arguing that President Trump should not be allowed to block people on his @realDonaldTrump account. He’s a government employee, the argument goes — he uses the account to communicate government information, and it violates principles of open government to block some people from receiving that information because they once said something mean about “The Apprentice.” (You can see oral arguments in the case from last month here.)

Obviously, news organizations are not governments and journalists are not presidents. There’s nothing potentially illegal here. But is it good practice, given the degree to which news organizations emphasize the need for both objectivity and the appearance of objectivity for its staffers? A politics reporter who blocked all the Democrats or all the Republicans on his beat would be obviously problematic — I’d argue far more so than a campaign sign on their front lawn, since it’s both an expression of opinion and an attempt to shape the sort of inputs he receives as a journalist. (If “I’m a fan of Candidate X” is bad, “I don’t even want to hear from Candidate Y” is worse.)

But most beats aren’t so cleanly divided among partisan lines, of course. And neither are Twitter users.

This is in some ways only the latest iteration of a roughly decade-old debate: Where do the boundaries of a reporter’s edited journalism and a reporter’s social media presence overlap? For the record, the Times’ social media policy seems to be pretty clearly on the don’t-block side in this case (emphasis mine):

If the criticism is especially aggressive or inconsiderate, it’s probably best to refrain from responding. We also support the right of our journalists to mute or block people on social media who are threatening or abusive. (But please avoid muting or blocking people for mere criticism of you or your reporting.)

Luckily, this particular crisis has resolved itself: McFaul reports that Vogel unblocked him this morning. But the issue will live on — at least until Jack Dorsey decides Twitter should really be a frozen-yogurt store or something.

Thanks @kenvogel for unblocking me. Moving on.

— Michael McFaul (@McFaul) April 17, 2019