Construction of an expansion of Egypt’s Suez Canal was supposed to take three years. But at the insistence of Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, it was built in only one — it opened earlier this month.

The day the new canal opened, August 6, was a national holiday. Dignitaries from around the world gathered to celebrate the project, which cost more than $8 billion.

On Twitter, though, a different story was playing out. Users co-opted many of the hashtags around the celebratory event and used them to question and satirize the government’s claims that the new canal would be an economic boon for Egypt. But because most of the tweets were in Arabic, many Western news organizations covered the dissent through posts that were in English. Much of the same happens with other news stories in countries where English is not the main language, from the Greek debt crisis to the ongoing political situation in Mexico.

In an attempt to improve translation of social media posts, Meedan — a hybrid for-profit and nonprofit group that focuses on global journalism and translation — has built Bridge, a mobile-first platform for translating social media posts.

In an attempt to improve translation of social media posts, Meedan — a hybrid for-profit and nonprofit group that focuses on global journalism and translation — has built Bridge, a mobile-first platform for translating social media posts.

“We’re addressing a problem that’s a flaw with the way Facebook and Twitter currently operate,” Ed Bice, Meedan’s CEO, told me. “Facebook and Twitter are not wired for human-generated translation at this time, so until then, until they get to that point, Bridge is a solution that allows us to take this content across language boundaries.”

Bridge is being built through Meedan Labs, the for-profit arm of the organization. Bice said the group had a contract with a social media company — he wouldn’t say which one — that “allowed us to build out the code base that we’re building bridge on. We have an unlimited license to develop bridge based on the fact that we brought it into them, and we believe that the prototype that we worked on for them will be expressed in the coming years.”

With Bridge, Meedan hopes to convey the nuances of language that often get lost in the machine translations that the social networks currently use. Meedan is planning on releasing an version of the iOS app in the fall for “limited usage,” An Xiao Mina, the Bridge product manager, said. The opening of the new Suez Canal was a first real test run of Bridge.

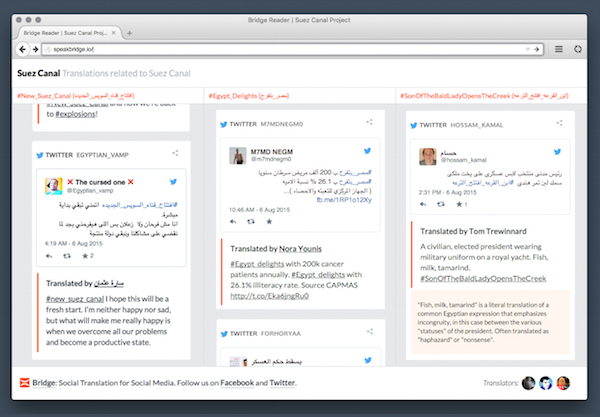

Meedan is currently focused only on Arabic, Spanish, and Portuguese, and for now it’s only offering it as an iPhone app, though there is a desktop reader that lets users follow different feeds of translated posts for various events. The reader should become available publicly within the next few weeks, Meedan said. It ultimately would like to add different languages and expand to Android as well. Additionally, Meedan is thinking about eventually monetizing the app.

“We are thinking about how we bring micropayments, virtual currencies, incentive models into an ecosystem where someone can request a translation, a journalist who is breaking a news story and needs an immediate translation can query the network with a request for translation,” Bice said. “We do have a view of creating a sustainable model around this, but we hope we can do that while keeping the values, the social core of what we want to do, both building a company and building technology.”

“We are thinking about how we bring micropayments, virtual currencies, incentive models into an ecosystem where someone can request a translation, a journalist who is breaking a news story and needs an immediate translation can query the network with a request for translation,” Bice said. “We do have a view of creating a sustainable model around this, but we hope we can do that while keeping the values, the social core of what we want to do, both building a company and building technology.”

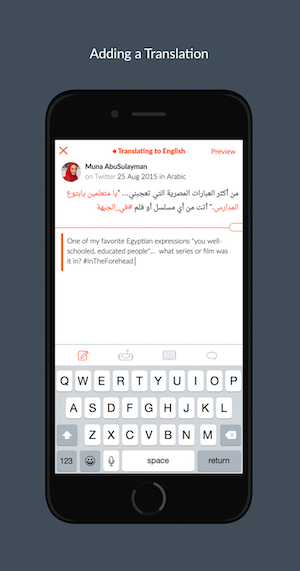

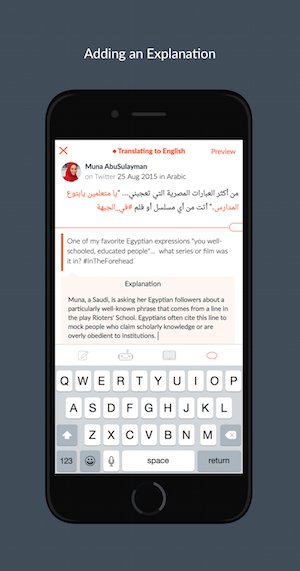

Translators using the app can follow different topics or users, and when they see a post they want to translate they can just tap on it. Once they get to the main translate screen, users can call up a machine translation from Bing. Mina said about half of the beta translators prefer to start “with machine translation so they can use it as a reference point or edit it directly.” Users can additionally add in explanations to the translations to provide additional context and background information. Within the app, users can also view a feed of others’ translations, where they can review the and help improve them.

Translators using the app can follow different topics or users, and when they see a post they want to translate they can just tap on it. Once they get to the main translate screen, users can call up a machine translation from Bing. Mina said about half of the beta translators prefer to start “with machine translation so they can use it as a reference point or edit it directly.” Users can additionally add in explanations to the translations to provide additional context and background information. Within the app, users can also view a feed of others’ translations, where they can review the and help improve them.

The app also includes an editable dictionary, originally sourced from BabelNet, so translators can look up words they don’t know and similarly add in phrases, including hashtags, so they’re consistent across all of Bridge’s translations. In the coverage of the Suez Canal opening, for example, Bridge translated popular Arabic hashtags such as #Egypt_Delights and #TheSonOfABaldHeadedWomanOpensTheCreek.

“The son of a bald lady opens a creek — that has a really beautiful rhyme in Arabic, so being able to express and annotate and mark that is really important,” said Tom Trewinnard, Meedan’s business development manager. “It adds a lot of depth, I think, to the understanding around what’s going on and how people are talking about these things. That’s as true for humor and satire as it is for hard news.”

Meedan is now working with a small group of vetted translators, but it plans to open up the platform to a wider audience. When that happens, users will be able to upvote and downvote translations, so editors can highlight the best translations on the platform.

Once a translation is published, it then appears in a completed translations feed in the app, and only the best translations will then continue onto Bridge Reader, where the original post is published above the translation. Bridge also lets users share the translations in a handful of ways. It’ll produce an embed code so users can add the original post and translation to their own pages. There’s an option to create a screenshot of the post and translation. Or users can share the translation on Twitter, and the translation will be produced as a reply to the original Tweet, so both the tweet and the translation will show up in their followers’ feeds.

Bridge only works with Facebook and Twitter posts for now, but as Meedan expands its language offerings, it would like to add different networks as well. So if it begins Chinese translations, Meedan would similarly likely begin translating posts on Sina Weibo, the popular Chinese social network.

“The idea here really is about reaching the online communities in a variety of different contexts,” Mina said, and as an example, she highlighted the recent minor earthquake in San Francisco where people from all sorts of communities were posting on various networks in different languages.”Often with big events, in different areas, the conversation…is very much spread out,” she said.

Translation has long been a focus for both Meedan and Mina individually. Meedan was founded in 2006; in 2009, the group translated tweets from Farsi during the Iranian revolution, then continuing its translation work throughout the Arab Spring. Meedan has also worked with journalist Paul Salopek’s Out of Eden Walk — a seven-year project where Salopek (a former Nieman Visiting Fellow) is recreating the spread of humanity from sub-Saharan Africa to the tip of South America — to translate social media posts from around the route of his walk.

Prior to her work at Meedan, Mina helped translate Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s Twitter account into English. MIT professor Ethan Zuckerman connected Mina with Bice and Meedan, and together they “worked to productize this [and] brainstormed what that product would like based on our mutual experiences,” Bice said.Bridge intimately fits in with Meedan’s other main project (Checkdesk, a free, open-source breaking news verification tool) and its larger mission of supporting journalists and freedom of expression around the globe. And as Meedan continues to develop Bridge, it will work to find new ways for both products to work together.

“[W]e have a vision of both of them integrating with each other,” Mina told me in a follow up email. “Both are being designed to support real-time news in global contexts — in order to do effective verification, we often need translation (both linguistic and cultural), and in order to do effective translation, we often need to verify facts and reports in the media we are translating.”