Editor’s note: John Keane is a professor of politics at the University of Sydney in Australia; he studies the ongoing evolution of democracy. Here, in a piece taken from the terrific Australian academia-meets-journalism site The Conversation, Keane examines the impact that the new generation of digitally savvy, intensely networked, online muckrakers is having on our perceptions of democracy.

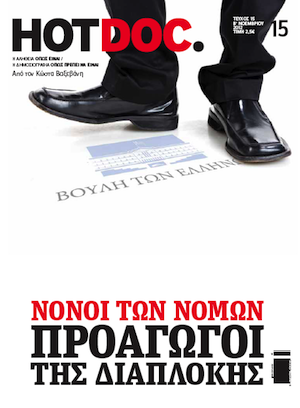

The spirit and institutions of Greek democracy are dying, but who really cares? Kostas Vaxevanis does. His name merits global attention because during the past year Hot Doc, the weekly magazine he owns and edits, has published a string of gutsy stories detailing the financial rip-offs that have brought his country to the point of economic, political and psychological breakdown.

The spirit and institutions of Greek democracy are dying, but who really cares? Kostas Vaxevanis does. His name merits global attention because during the past year Hot Doc, the weekly magazine he owns and edits, has published a string of gutsy stories detailing the financial rip-offs that have brought his country to the point of economic, political and psychological breakdown.

Vaxevanis began by exposing the huge kickbacks on weapons contracts allegedly pocketed by a former defence minister, who is now behind bars, awaiting trial. Hot Doc then implicated the central bank of Greece in shorting the country’s debt by local speculators. It tracked the issuing of large unsecured loans (known locally as thalassodaneia) by private banks. Last month brought its biggest and most controversial scoop: the publication of a list of 2,000 rich and powerful Greeks with funds stashed in Swiss bank accounts. Hot Doc sales and online hits rocketed. Vaxevanis was arrested. Cold-shouldered by mainstream media, he was pelted with abuse, targeted by assassins and accused by state authorities of violating privacy laws and “turning the country into a coliseum.”

Vaxevanis remained defiant. “We’ll continue doing our job,” he said, “and that is to uncover everything that others wish to hide.” Earlier this month, he was vindicated by an Athens court. A judge ruled that he’d acted for the public good. Events then took a macabre turn: the Athens public prosecutor’s office announced his re-trial in a higher level misdemeanour court. If convicted, he could suffer a two-year prison sentence.

Brave Kostas Vaxevanis belongs to the age of monitory democracy. He’s a new muckraker, an exemplar of a distinctively 21st-century style of political writing. To describe him this way is to give new meaning to a charming old Americanism, an earthy neologism from the late nineteenth century, when muckraking referred to journalism committed to the cause of publicly exposing arbitrary power.

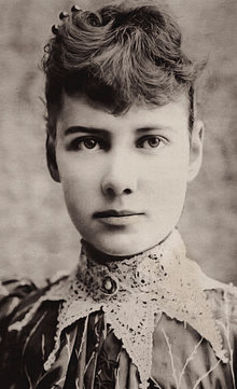

Most people have today forgotten writers like Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell and Jacob Riis. Their condescension by posterity is shameful. For the muckrakers, true to their name, took advantage of the widening circulation of newspapers, magazines and books made possible by advertising, and by cheaper, mass production and distribution methods, to offer sensational public exposés of grimy governmental corruption and waste, business fraud, and social deprivation. Among my favourites from this period was the Pennsylvania-born journalist Nellie Bly. She did something daring and dangerous: for Joseph Pulitzer’s newspaper the New York World, Bly faked insanity to publish an undercover exposé of a woman’s lunatic asylum. Other muckrakers openly challenged political bosses and corporate fat cats. They questioned industrial progress at any price. The muckrakers took on profiteering, deception, low standards of public health and safety. They complained about child labour, prostitution and alcohol. They called for an end to city slums. They poured scorn on legislators, portraying them as pawns of industrialists and financiers, as corrupters of the principle that representatives should serve all of their constituents, not just the rich and powerful.

Most people have today forgotten writers like Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell and Jacob Riis. Their condescension by posterity is shameful. For the muckrakers, true to their name, took advantage of the widening circulation of newspapers, magazines and books made possible by advertising, and by cheaper, mass production and distribution methods, to offer sensational public exposés of grimy governmental corruption and waste, business fraud, and social deprivation. Among my favourites from this period was the Pennsylvania-born journalist Nellie Bly. She did something daring and dangerous: for Joseph Pulitzer’s newspaper the New York World, Bly faked insanity to publish an undercover exposé of a woman’s lunatic asylum. Other muckrakers openly challenged political bosses and corporate fat cats. They questioned industrial progress at any price. The muckrakers took on profiteering, deception, low standards of public health and safety. They complained about child labour, prostitution and alcohol. They called for an end to city slums. They poured scorn on legislators, portraying them as pawns of industrialists and financiers, as corrupters of the principle that representatives should serve all of their constituents, not just the rich and powerful.

Our media-saturated age of monitory democracy is reviving and transforming muckraking in this old sense. New muckrakers like Kostas Vaxevanis put their finger on a perennial problem for which democracy is a solution: the power of elites always thrives on secrecy, silence and invisibility. Gathering behind closed doors and deciding things in peace and private quiet is their speciality. Little wonder then that in media-saturated societies, to put things paradoxically, muckrakers ensure that unexpected “leaks” and revelations become predictably commonplace. Despite his neglect of the shaping effects of communications media, the French philosopher Alain Badiou is right: everyday life is constantly ruptured by mediated “events.” They pose challenges to both the licit and the illicit. It is not just that stuff happens; muckrakers ensure that shit happens. Muckraking becomes rife. There are moments when it even feels as if the whole world is run by rogues.

The net effect is that under conditions of communicative abundance the core institutions of representative democracy have become easy targets of rough riding.

Muckraking is a controversial practice, certainly, but there’s no doubt it has definite political effects on the old institutions of representative democracy. Public disaffection with official “politics” has much to do with the practise of muckraking under conditions of communicative abundance. In recent decades, much survey evidence suggests that citizens in many established democracies, although they strongly identify with democratic ideals, have grown more distrustful of politicians, doubtful about governing institutions, and disillusioned with leaders in the public sector.

Politicians are sitting ducks. The limited media presence and media vulnerability of parliaments is striking. Despite efforts at harnessing new digital media, parties have been left flat-footed. They neither own nor control their media outlets and they’ve lost much of the astonishing energy displayed at the end of the 19th century by political parties, such as Germany’s SPD, which at the time was the greatest political party machine on the face of the earth, in no small measure because it powerfully championed literacy and was a leading publisher of books, pamphlets and newspapers in its own right.

The net effect is that under conditions of communicative abundance the core institutions of representative democracy have become easy targets of rough riding. Think for a moment about any current public controversy that attracts widespread attention: muckraked news and disputes about its wider public significance typically begin outside the formal machinery of representative democracy. The messages become memes quickly relayed by many power-scrutinising organisations, large, medium and small. They often hit their target, sometimes from long distances, often by means of boomerang effects. In the media-saturated world of communicative abundance, that kind of latticed or networked pattern of circulating controversial messages is typical, not exceptional. It produces constant feedback effects: unpredictably non-linear links between inputs and outputs.

The new dot.org muckrakers don’t simply give voice to the voiceless. Their aggressive muckraking triggers echo effects which spell deep trouble for conventional understandings of journalism.

Who or what drives the new muckraking? The temptations and abuses of power by oligarchs, certainly. The criminal obscenities, hypocrisies and political stupidities of those responsible for the deep crisis of parliamentary democracy in Greece and the wider Atlantic region, no doubt. The decline of parties and representative politics and strengthening democratic sensibilities against arbitrary power also play their part. But of critical importance is the advent of communicative abundance. Just as the old muckrakers took advantage of advertising-driven mass production and circulation of newspapers, so the new muckrakers are learning fast how to use digital networks for political ends.

The new muckraking isn’t the effect of new media alone, as believers in the magical powers of technology suppose. Individuals, groups, networks and whole organisations make muckraking happen. Yet buried within the infrastructures of communicative abundance are technical features that enable muckrakers to do their work of publicly scrutinising power, much more efficiently and effectively than at any moment in the history of democracy.

From the end of the 1960s, a communications revolution has been unfolding. It’s by no means finished. Product and process innovations have been happening in virtually every field of an increasingly commercialised media. Technical factors, such as electronic memory, tighter channel spacing, new frequency allocation, direct satellite broadcasting, digital tuning and advanced compression techniques, have made a huge difference. Yet within the infrastructure of communicative abundance there’s something more important, more special: its distributed networks.

In contrast, say, to centralised state-run broadcasting systems of the past, the spider’s web linkages among many different nodes within a distributed network make them intrinsically more resistant to centralised control. The network is structured by the logic of packet switching: information flows are broken into bytes, then pass through many points en route to their destination, where they are re-assembled as messages. If they meet resistance at any point within the system of nodes then the information flows are simply diverted automatically, re-routed in the direction of their intended destination.

It is this packet-switched and networked character of media-saturated societies that makes them so prone to dissonance. Some observers (Giovanni Navarria is among them) claim that a new understanding of power as “mutually shared weakness” is needed for making sense of the impact of networks on the distribution of power within any given political order. Their point is that those who exercise power over others are subject constantly to muckraking and its unforeseen setbacks, reversals and revolts. Manipulation and bossing and bullying of the powerless become difficult. The powerless readily find the networked communicative means through which to take their revenge on the powerful. The consequence: power disputes follow unexpected pathways and reach surprising destinations that have unexpected outcomes.

Navarria and others have a point. Innovations such as the South Korean site OhmyNews, UK Uncut, California Watch and Mediapart (a Paris-based watchdog staffed by a number of veteran French newspaper and news agency journalists) help radically alter the ecology of public affairs reporting and commentary. The new dot.org muckrakers don’t simply give voice to the voiceless. Their aggressive muckraking triggers echo effects which spell deep trouble for conventional understandings of journalism.

The disease of dysfunctional democracy is spreading. Cynicism grows. Political drift is the new norm.

The days of journalism proud of its commitment to the sober principle that “comment is free, but facts are sacred” (that was the phrase coined in 1921 by the Manchester Guardian’s long-time editor C.P. Scott) are over. References to fact-based “objectivity,” an ideal that was born of the age of representative democracy, are equally implausible. Talk of “fairness” (a criterion of good journalism famously championed by Hubert Beuve-Méry, the founder and first editor of Le Monde) is also becoming questionable. In place of the rituals of “objectivity” and “fairness” we see the rise of adversarial and “gotcha” styles of journalism, forms of writing that are driven not just by ratings, sales and hits, but by the will to expose wrongdoing. Muckraking sometimes comes in highly professional form, as at London’s The Guardian, which played a decisive role in the phone-hacking scandal that hit News Corporation in mid-2011. In other contexts, muckraking equals biting political satire, of the deadly kind popularised in India by STAR’s weekly show Poll Khol, which uses a comedian anchorman, an animated monkey, news clips and Bollywood soundtracks (the programme title is translated as “open election” but is actually drawn from a popular Hindi metaphor which means “revealing the hidden story”).

Thanks to the new muckraking, rough riding of the powerful happens — on a scale never before witnessed. Contrary to the pessimists and purists, democratic politics is not withering away. In matters of who gets what, when and how, thanks to the new muckrakers, nothing is ever settled, or straightforward. Our great grandparents would find the whole process astonishing in its democratic intensity. There seems to be no end of scandals. There are even times when so-called “-gate” scandals, like earthquakes, rumble beneath the feet of whole governments.

Skeptics say that muckraking has gone too far, that it breeds distrust and disaffection, that it’s poisoning the spirit of democracy. The case of Kostas Vaxevanis, his refusal to let Greek democracy die, shows that kind of objection is both premature and out of touch. On balance, all things considered, muckraking has always been a good and necessary thing for democracy. It’s now becoming a life-and-death imperative. We’re living in confused times when the political dirty business of dragging arbitrary power from behind curtains of secrecy is fundamentally important. “Greece is ruled by a small group of politicians, businesspeople and journalists with the same interests,” Vaxevanis said recently. In a Twitter post, he noted the consequence: “While society demands disclosure, they cover up.”

He’s right, and his point is surely relevant not just for Greece, but for democratic countries otherwise as different as Japan, India, Spain, and the United Kingdom. The disease of dysfunctional democracy is spreading. The gaps between rich and poor, the powerful and the powerless, are widening. Public disaffection with politicians and parties flourishes. Cynicism grows. Dropping out is becoming common. Worst of all, where all this leads is becoming ever less clear. Political drift is the new norm.

Watch out, citizens.

John Keane is director of the newly-founded Institute for Democracy and Human Rights (IDHR) and professor of politics at the University of Sydney and the Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin (WZB). His most recent book, The Life and Death of Democracy (2009), was short-listed for the 2010 Non-Fiction Prime Minister’s Literary Award.

John Keane is director of the newly-founded Institute for Democracy and Human Rights (IDHR) and professor of politics at the University of Sydney and the Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin (WZB). His most recent book, The Life and Death of Democracy (2009), was short-listed for the 2010 Non-Fiction Prime Minister’s Literary Award.This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article.