Flipping through old magazine and newspaper ads is like throwing the switch on the world’s simplest time machine. Suddenly it’s 1969, the Apollo 11 astronauts have just made the round trip from the moon, Abbey Road just dropped, and for the low price of $29.95 you can enjoy an “electric computerized football game [that] lets you and your opponent call offensive and defensive plays.”

This is the benefit a paper like The New York Times finds in its archive: the ability to pluck moments from the historical record out of the past — the small steps and giant leaps, but also the assembled fragments and cultural artifacts that often share space on the page. While you can dig deep into the stories of the past with TimesMachine, uncovering specific ads isn’t as easy. The team in The New York Times R&D Lab wants to rectify that with Madison, a new tool for identifying ads across the newspaper’s archive. What makes Madison different is that it relies on Times readers — not a bot or algorithm — to do the tricky work of spotting and tagging the ads of the past.

“We have 163 years of what is often referred to as the first draft of history, and I think one of the areas we’re interested in is finding new ways to bring that archive to life,” said Alexis Lloyd, creative director for the R&D Lab.

The Times R&D Lab sometimes seems like the newspaper equivalent of Q Branch, tasked with developing fun, futuristic tools that can serve the institution in unusual ways. Instead of jetpacks and exploding pens, the R&D Lab tries to find ways to make it easier for the public to get their hands on Times content. Sometimes that’s demonstrated in finding new surfaces to display news throughout the home, or tools that visualize how news spreads across social channels. And, sometimes, it’s a broach that lights up when someone mentions something you’ve been googling. Madison is just a part of a bigger R&D project called Hive, a platform for creating crowdsourcing projects off any collection of data. News organizations are asking readers for help sifting through collections of data more and more often. Sometimes its asking readers to help track spending on campaign ads, or detail the expenses of their member of parliament. Hive was designed to simplify that process by making it easier to “import assets, define tasks, and set validation criteria,” Lloyd explained in an email. That means the Times could find plenty of inward and outward looking uses for Hive in the future. And they plan to let others in on the fun as well by making Hive open source.Lloyd said one of the things the R&D Lab is focused on is the idea of semantic listening — pulling clues and ideas about the meaning of something by looking at what surrounds it. Chronicle, which visualized word usage in the Times, and Curriculum, which creates a list of topics based on R&D Lab members’ web browsing, are two examples of that. Madison, by extension, is an effort to figure out what ads are in relation to stories, and what those ads might be selling. The benefit to the Times is being able to build new products and tools that could be useful to historians, journalists, or researchers for period-specific TV dramas to dig into the past.

Madison serves a few purposes. With the release of TimesMachine, the company made it easier for people to browse old editions of the paper. But it’s an incomplete corpus compared to the print original. With Madison, the Times can build a more complete archive of everything published in the paper since it first ran off the presses in 1851, Lloyd said. But it’s also a way of getting Times readers more engaged with the paper through a little lightweight media archeology. “I think it gives our readers a look into a piece of the archive and history that has not traditionally been easy to see,” Lloyd said.Getting the crowd involved also happened to be an efficient way of separating ads out from other parts of the paper, said Jane Friedhoff, a creative technologist with the R&D Lab who worked on Madison. Writing on the R&D Lab blog, Friedhoff outlined why using algorithmic methods to hunt for ads was difficult:

However, the digitization of our archives has primarily focused on news, leaving the ads with no metadata —making them very hard to find and impossible to search for…Complicating the process further is that these ads often have complex layouts and elaborate typefaces, making them difficult to differentiate algorithmically from photographic content, and much more difficult to scan for text.

There are three basic tasks users can perform in Madison: finding, tagging, and transcribing ads. With any crowdsourcing project, you have to balance the need for the right information against how you incentivize users to do a job, Friedhoff told me. “When we were designing Madison, we had to think of the kinds of data we were trying to get, but also ways to make it easier for people to participate,” Friedhoff said. Rather than asking people to fill out a long form, they broke it up into smaller, simpler jobs, she said.

One challenge: 163 years of newspapers is a lot of ads. Asking readers to dive into that on their own, to pick somewhere on a continuum from the Spanish–American War to the War on Drugs, is tough. Lloyd said their solution was to limit Madison by decade, starting with only ads from the 1960s. As they amass metadata on those ads, they’ll open up Madison to other years.

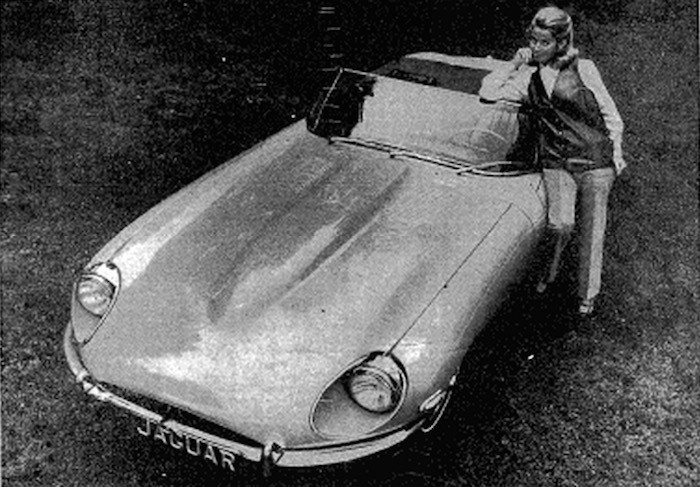

Friedhoff said one of the biggest motivations for using Madison is the search for “interestingness” — the discovery of ads that capture the zeitgeist of the era or, alternatively, show how far we’ve come. The ability to show off weird Canadian whiskey ads and announcements from the Record Club of America is pretty fun, as far as enticements go. “That, to me, is where the delightful part of this is, the part you want to share with your friend,” Friedhoff said.

For journalists, it can be easy to overlook advertising as the thing that helps pay the bills and adds a little color to a daily sea of black and white. But ads can also provide context and meaning around the news, telling us just as much about the past. “The news gives us that real narrative about what’s happening in the world, and the editorial judgment and control that goes into creating an objective and reliable narrative in that,” Lloyd said. “Advertising is content, but freer from those constraints and gives a look at history and what was happening at the time.”