There’s a new news app that’s made quite a splash. From headlines like “Timeline Is A Beautiful News App That Makes It Easy To See The History Behind A Story” to being Apple’s best app of January, Timeline’s gotten a warm welcome.

Named Best App of January by the @AppStore! A real team effort. #Apple pic.twitter.com/AqNcVxb4Fg

— Timeline (@Timeline_Now) February 6, 2015

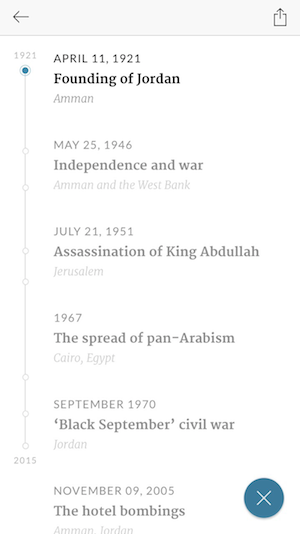

Timeline is, indeed, an elegant app, built around providing historical context to topical stories, with a smooth interface. You have work off for Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, but don’t know much about the civil rights era? No problem: Timeline has a compact, scrolling solution for that.

It’s helped that Apple’s supported the app — the App Store has listed Timeline as a featured news app almost since launch. Timeline cofounder and venture capitalist Tamer Hassanein acknowledges what a blessing that was for his app. In his years of working at startups in Silicon Valley, he says, “I haven’t met a single company that’s been featured immediately after coming out.”

Hassanein says he got involved with Timeline because he was passionate about the idea. “The way I feel about Timeline is the way you feel when you travel somewhere,” he says. “It completely changes, not your perception, per se, but opens your mind to this whole other way of life.”

The original conception of Timeline, which Hassanein developed with cofounder and Russian investor Leon Semenenko, was desktop-oriented. Using a map view, users were supposed to explore “people, events and brands” across time. But in March 2014, Hassanein decided the company needed to pivot, saying to Semenenko, “I think there’s an approach here that will get us to our end goal, and I think it’s contextualized news.”

A focus on news could be the hook that helps achieve the goal of bringing history to users where they are — on mobile. “What discerning people do is, they hear something or read an article, then they Google it, and then they read the Wikipedia page,” says Hassanein. The goal of Timeline is to take that impulse and satisfy it in a more efficient, informative and beautiful way.

To accomplish this, Timeline hired a small group of editorial staffers to create content, in addition to freelance contributors. Stories are based on predetermined news calendar events, breaking news, or staff interests. Writers turn to standard news outlets for research (citing them where appropriate), or, in some cases, rely on personal knowledge of an issue. Originally, the company wanted to hire historians to help create content for the app, but even in the rare instance the historians could be convinced, they ran into trouble. “Historians don’t understand the importance of deadlines in the way journalists do,” Hassanein says.

http://instagram.com/p/ydQvobre7x/?modal=true

In the beginning, it took the team — which includes individuals in Washington and London as well as product staffers in Vancouver — a full work day to write a single timeline, but now they can churn them out in about five hours. For the time being, they’re publishing at a rate of two or three a day, though that could ramp up in the near future. But Hassanein isn’t interested in breaking news, which he calls “a commodity,” or in pushing out dozens of stories in order to generate clicks.

“Part of what we’re doing here is trying to focus on things that are important, and create depth,” he says. “My dad, as a kid, had two pairs of pants. He used to say, ‘The absence of choice clears the mind marvelously.'”

That’s a lovely sentiment, but is it a winning business strategy? The challenges that Timeline will face on the market are sort of obvious. From Fast Company:

I can’t imagine anyone—even history nuts like me — wanting to travel back in time for every single story. In short, the app feels less like the sort of thing you’d hit repeatedly through the day to see what was new in the world, and more like something you’d spend occasional quality time with when you had the time to really dig into it.

From TechCrunch:

The bigger question is whether consumers are actually interested in this format — talking about historical context can sound an awful lot like the news equivalent of eating your vegetables, the opposite of pet slideshows and clickbait headlines.

From Gigaom:

Timeline’s real struggle may come in the form of app store noise. Despite the addictive nature of the app, its initial premise is a tough sell to the procrastination masses. Surf history instead of Kim Kardashian selfies during your down time? Not a sexy pitch.

Though Hassanein is new to news apps, he’s not new to building mobile apps. He worked for Zong, a mobile payments company acquired by eBay for $240 million in 2011. He then founded Foghorn Games, which created a popular bingo game for iPad and was acquired by Playsino in 2012.

Hassanein is also a partner at Rising Tide Fund, a venture firm he started in 2011 with his father, well-known investor and entrepreneur Ossama Hassanein. Both men are also listed as partners at Newbury Ventures, which the elder Hassanein founded. Rising Tide has invested in a number of companies, including Fuel, where the younger Hassanein was president until 2012 and now sits on the board, and Quanenergy, where he is board director.

http://instagram.com/p/x0vugJLe5R/?modal=true

Conventional wisdom has it that, to make big money on apps, you have to build a massive user base. To make money in media, you have to build a loyal audience — or at least an audience that will regularly spend quality time with your content. Without the draw of breaking news and push notifications1, and with such a small number of stories per day, Timeline doesn’t seem like a natural candidate to reach that sort of scale.

But Hassanein suggests that there could be unconventional ways to monetize. “A big part of what we’re doing is building a proprietary database, drawing from a number of well-established, open databases of facts, and organizing it in such a way that when we want to create a timeline, we’re able to do so reasonably quickly,” he says. “Eventually, we do want to make this database, and potentially our tools, available to media companies, brands, individuals, and cities for use in different contexts.”

But Hassanein suggests that there could be unconventional ways to monetize. “A big part of what we’re doing is building a proprietary database, drawing from a number of well-established, open databases of facts, and organizing it in such a way that when we want to create a timeline, we’re able to do so reasonably quickly,” he says. “Eventually, we do want to make this database, and potentially our tools, available to media companies, brands, individuals, and cities for use in different contexts.”

Though Hassanein says monetizing the database is some time and a few data engineer hires down the road, brands could make good use of what Timeline has to offer. One could imagine ad clients being interested an easily searchable database of historical facts that can be easily tied to current events, allowing brands, in Hassanein’s words, to “creat[e] affinity with [their] customers.”

Timeline is also thinking about ways that their content could be chunked up and distributed on social platforms; though they’re not there yet, Hassanein says they’re working on building a cards-based infrastructure for the app (think Circa or Vox). These cards — or whole timelines — could be embedded onto any webpage, a feature that could be appealing to other publishers and to brands.

“We did a timeline on What is time? What if Rolex were to sponsor that, or Swatch, or whoever?” wonders Hassanein. “We did one on God and gay marriage; there could be a church that sponsors it, or an organization that supports gay and lesbian people. There are always various interests.”

After successful ventures in gaming and mobile banking, and with a couple of funds to help run, I was curious to know what drew Hassanein to mobile news. It’s a hot market, to be sure; at The Awl, John Herrman describes in detail how and why media companies are funneling money, time, and content into apps. But as someone who has been — and whose family has been — playing successfully in Silicon Valley for some time now, why did Hassanein see Timeline as a good bet?

“If you compare today versus ten, fifteen years ago, the cost of starting a company has dropped by orders of magnitude,” he says. With cloud computing, there’s no need to worry about server space; any website can scale with relative ease. If you have an idea, he says, it’s quite simple to build a landing page, set up a Facebook account, and see how people react. In an environment like that, with millions more people coming online all the time, why not take a risk on media?

Says Hassanein: “Testing out a hypothesis is very cheap.”