The investigation went largely unnoticed until 2016, when the same real estate company was implicated in the collapse of a bank. The ex-chief of staff and the company, named in the Apache story from 2013, demanded €350,000 in damages from Apache.

The company’s charges, however, caused an outpouring of support for Apache. Experts in media law roundly condemned the court case. A crowdfunding campaign and a benefit concert — organized by a standup comedian, Wouter Deprez, with the help of Apache and the concert hall Roma — raised €121,000, enough to cover court costs.“The cost of the lawyers alone would have ruined us,” Karl van den Broeck, Apache’s editor-in-chief, told me. “The case brought with it a wave of sympathy for us, and actually made us stronger.”

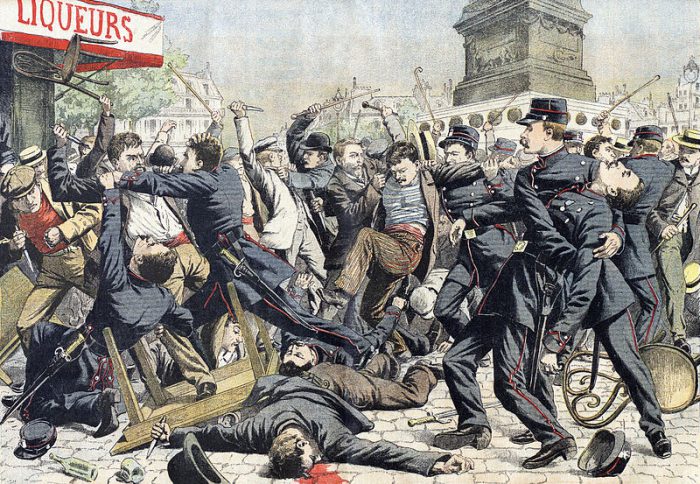

Apache was founded in 2009 by several journalists laid off from other Belgian news outlets (its early backers included Georges Timmerman, Tom Cochez, Bram Souffreau and Jan Vangrinsven). The organization was established partly in response to an imbalance of media ownership in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking region of Belgium. The site has since grown to a modest staff of nine, seven of whom are reporters, with additional freelance support. (The name Apache does not refer directly to the Native American tribe, but rather to the 19th-century Parisian subculture — though that subculture’s name did refer, problematically, to the tribe. It’s pronounced ah-PAHSH, not uh-PATCH-ee.)

“The Flemish media landscape is very strongly concentrated in the hands of two to three media groups, who in turn are controlled by one or two families,” van den Broeck told me. “That is a very high concentration of power in the hands of individuals who have other commercial activities. So journalism sometimes clashes with the interests of the owners.”

Indeed, in a 2016 report, the Flemish media regulator noted that “the 7 most important paying Flemish newspapers have since [2013] been published by only two publishers, De Persgroep and Mediahuis.”

Apache is paywalled and operates under a co-op model — the organization is owned by its staff and its readers — “because we see it as the best way to guarantee our independence,” van den Broeck said. Each share in Apache costs €50, and shareholders are required to buy at least three shares initially. As of this October, Apache has just over 1,000 shareholders, raising just short of €500,000 to date. Shareholders can elect members to Apache’s board of directors, although shareholders only get one vote regardless of the number of shares they own. In this way, shareholders do hold some influence on the general management of Apache, but the editorial operations remain independent, van den Broeck emphasized.

“The cooperative does not influence the editors of Apache,” he said. “There is consultation between the board of directors and the editors, but that does not go to the level of articles. In that sense we are a protected environment for journalists.”

Apache also sells subscriptions to its site, distinct from shares, although shareholders do receive a one-year subscription. A basic subscription costs €80 a year, readers can also choose to subscribe for €120 a year to support Apache. The site now has around 3,500 subscribers. Apache maintains a porous paywall, which allows only paid subscribers to read most articles, though it regularly makes articles available for free and lets non-subscribers read individual articles through links shared by other subscribers (a feature used by subscription-driven outlets like Silicon Valley’s The Information and Dutch outlet De Correspondent).

“Maybe it is a purist attitude we have, but we believe that being funded by your readers is the best guarantee for independence. Using advertisements, subsidies or patronage has the risk of running into conflicts of interest,” Van den Broeck said. “We do not use advertisements and we only use government subsidies for specific projects, not to finance our day-to-day operations.”

At the moment, Apache still operates at a loss: “We are a startup. Our business plan is on schedule, but we still need to grow to become break-even,” van den Broeck admitted. The site hopes to have around 10,000 subscribers by early 2019. For now, it is financed through a combination of the funds it raises by selling shares and subscriptions in addition to some loans and government project subsidies.

Since 2009, Apache has frequently landed scoops with national repercussions. Its articles were helped expose the Belgian side of the French “Kazachgate” scandal where French politicians colluded with Kazakh businessmen during a corruption case. Their coverage included exposing a fake news site from Kazakhstan that was targeting Belgians around the time of the scandal. Another recent scoop showed how health insurance funds sold patient records to pharma companies.

“During the last few years, several parliamentary inquiries were launched in Belgium, and several of those have been directly caused by articles in Apache,” van den Broeck said, pointing out that whenever the site breaks news, it sees its subscriber numbers go up. “You need to conquer each subscriber individually, but whenever a dossier receives wider attention, we see more subscribers sign up.”

The court case against Apache from the real estate company that for damages was in particular a boon for subscriptions.

“We doubled our subscribers during that period, we went from 1,500 to 3,000,” van den Broeck told me. That same year, Apache had also increased the price of a subscription from €39 to €80 per year, but “we did not lose any subscribers; we actually doubled the number.”

Van den Broeck is hopeful that Apache’s co-op structure and reliance on subscriptions rather than advertising will continue to shield it in what he sees as a world that needs investigative journalism more than ever.

“Thanks to world leaders like Donald Trump there is more oxygen for investigative journalism. In times of fake news people look for something to hold onto, and they increasingly find that in quality journalism,” he said. “I think investigative journalism in Belgium is getting stronger again. Publishers are realizing that further cuts to newsrooms do not make sense. The only thing standing between a newspaper and whatever is appearing on social media is precisely old-fashioned, good journalism that has been made according to the rules of the trade.”