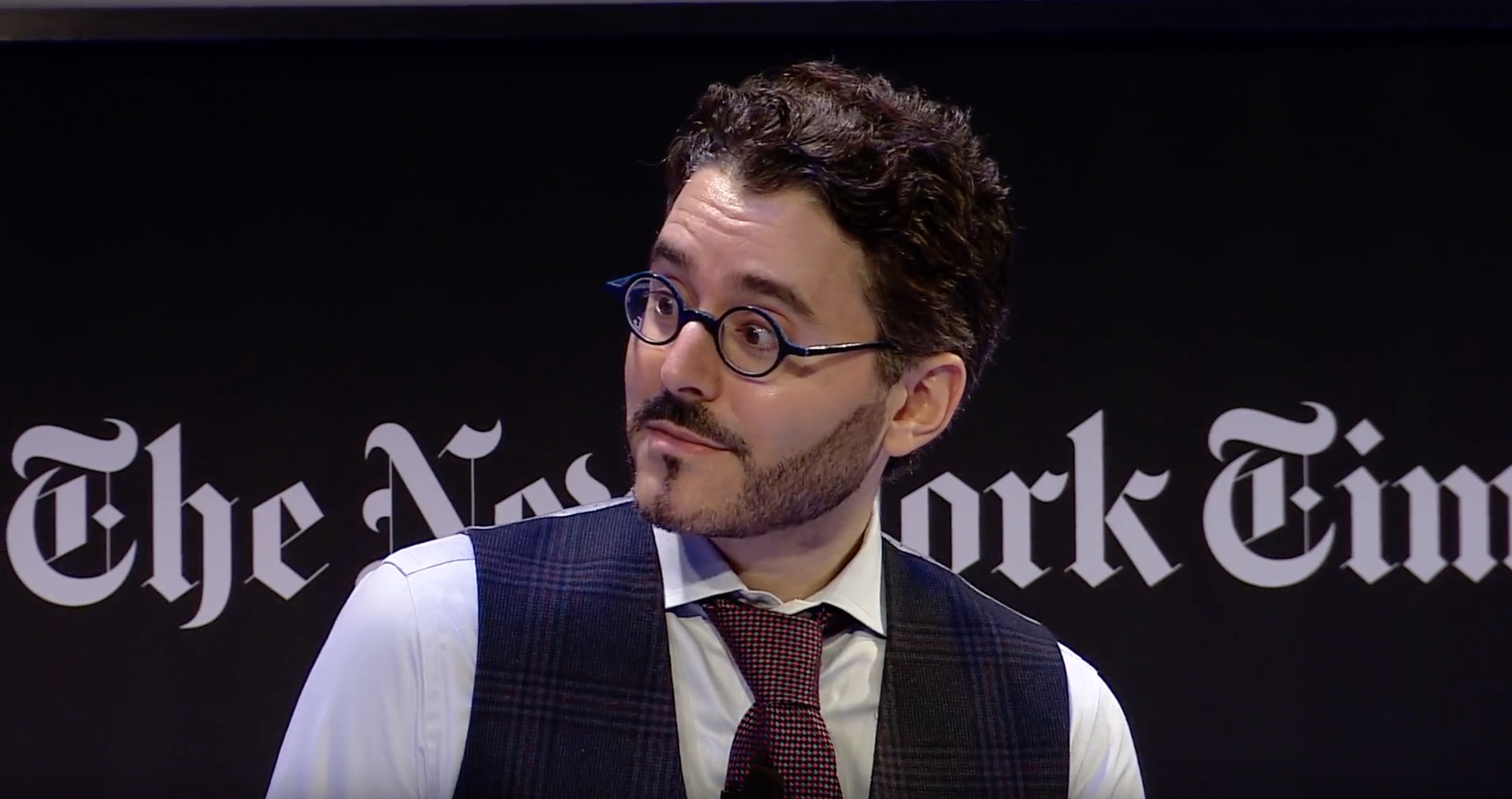

Is he comfortable with that new cloak?

“I don’t know that I’ll ever be comfortable being a personality, because it never occurred to me that the way that I talk and the way that I respond to people, or how I listen, would become something that people would focus on,” Barbaro, the show’s host and managing editor, told me. “It’s been really intriguing to watch people seize on just the way that I am, and in some ways I can’t help being, and decide that they like it, or they don’t like it, or something in between.”

Barbaro is self-effacing about his newfound career and fame, but it’s clear to the millions who have downloaded The Daily that Barbaro has it — a mix of voice, authenticity, knowledge, and likability that no algorithm could produce.

I asked Times executive editor Dean Baquet what most surprised him about The Daily’s success. “I’m most surprised, frankly, that the Times found a voice so easily. Michael was a great political reporter, one of the best. But who knew he could create such a persona that feels so much like the Times?” Baquet credits both Sam Dolnick and Kinsey Wilson, who championed the big audio push when he served as the paper’s chief digital executive, with the achievement.

As the audience for the show reaches new heights — it had 3.8 million unique listeners in August, the Times says — the paper is plotting how to bottle this accidental alchemy. Consider it an admixture of the best of both public radio and the Times itself, operating in a way the storied institution rarely can — as a startup.

“Barbaro’s been here for a long time,” said Dolnick, the assistant masthead editor responsible for the newsroom’s audio initiative. “I think more than anything it’s that nobody here had a legacy in public radio. We didn’t have old habits to unlearn.”

Dolnick says the Times’ transition from print to digital “has been this long process where we had to figure out how to navigate a new world. How to bring a print habit into the digital world — how to leave some behind and bring some along. It’s hard. We’re doing it, but it’s hard. Then you see some of these new digital players come in, and they were just off to the races because they were just able to start without any of the legacy of print.

“Now for once, we get to do that in audio.”

In August of last year, the Times’ fledgling audio team created the twice-weekly, election-oriented The Run-Up.

“That was our early testing ground,” says Samantha Henig, the Times’ editorial director for audio. “Just the fact that we kind of turned that around in a matter of weeks, and decided to just jump in as soon as [executive producer] Lisa [Tobin] started, and to launch something and learn. That gave us confidence to launch a daily show earlier than we maybe otherwise would have.

“Of course, finding Michael, finding what a natural talent he was, and that sort of special sauce that’s his chemistry with his colleagues — people talking like reporters instead of talking like radio personalities.”

Barbaro serves, in effect, as the voice of the Times’ readers — more curious about the why and how than the what and when, seeking the deeper story behind the headline. Barbaro maintains both his and the Times’ journalistic cred, but shortens the distance between it and us. He’s managed to reveal a new kind of Times in ways that have surprised not just him, but hundreds in the Times newsroom as well.

That’s the other big thing about The Daily. This is a New York Times program, and that has made all the difference. The Daily debuted in an already crowded market for newsy podcasts. Sensing the exploding podcast audiences and the video-like ad rates they can fetch, who hasn’t launched a podcast lately?

The Daily, though, builds on a unique foundation: the 1,300-strong Times newsroom. Times readers — including its subscribers, now numbering about 2 million digital and 1 million print — have long depended on the Times’ journalists’ knowledge and expertise. That’s never been more true than in these oddest of American political times. But The Daily applies a layer of nuance atop the words, the photos, and the infographics.

How much do Times journalists have to watch what they say on the show, especially in the context of the paper’s new social media guidelines? (More than a hundred Times journalists have found their way into the recording studio so far.) That will be an ongoing question, but remember: The Daily is a highly edited show, not a live one.

Habit is the key word here, one that’s connected to reminders to subscribe to the Times and to a 30-second midroll ad. While the name The Daily appears prosaic, it’s entirely right: Subscribers who pay the Times hundreds of dollars a year do so in strong part out of the habits they’ve built. The Daily then reinforces that habit, the digital audio equivalent of — what did they call those things they threw on our driveways every day? Ah, newspapers.

“This is the birth of a franchise for us that can live on and on in many different mediums for a long time,” says Dolnick.

The Times now employs 16 full-time staffers in audio, with more positions — including in digital engineering development — to be added into next year.

“I think the next generation of readers, their first touchstone, their most meaningful touchstone with The Times, will be The Daily,” Dolnick says. “That’s a big deal that didn’t exist just a year ago. We’re already reaching a huge number of people. They’re younger, they’re mobile.”

Already being planned: expanding The Daily to a sixth day each week, and This American Life-like extensions of the program.

The audio team, headed by Henig (as the editorial director responsible for “threading together” the Times’ audio’s audience, product, and business) and Tobin (as the executive producer responsible for the show’s production) have formed a partnership that marries public radio knowledge and production chops with Times newsroom intelligence.

“Everyone, all of the producers on the team who are used to working with kind of traditional radio hosts, are so struck by how Michael — because he is a reporter, and because he doesn’t come from radio — he doesn’t actually know what it means to be a host,” Henig says. “He doesn’t fall into some of the traps of a traditional host.”

He still does his own booking of guests on the show, for instance — a job typically left to producers in radio. “I don’t think he realizes that that’s very unusual for a host, because as a reporter, you do your own booking,” Henig says. “You call your sources, and you figure out when you’re gonna talk to them. In the case of The Daily, these are his colleagues, and so he wants to be the one to send an email asking people to talk, and he wants to be the one to send a thank-you note the next morning to say that it was great.”

I spoke with Barbaro about the joys and challenges of doing something wholly new. Here’s our conversation, edited lightly for clarity.

One of my favorite things that we ever did on The Daily was we had Maggie Haberman, who is a regular and just an extraordinarily accomplished White House reporter. She walks into the studio in Washington, and just starts to sing. Maggie loves to sing.

She started singing a famous old number. I think it’s “I’m Beginning to See the Light” — I can give you the exact name of the song. It was one of those old, kind of big-bandy songs.

She’s singing. And she’s singing in the clear, no music. She has a beautiful singing voice. Then, Lisa [Tobin] decided to call up a musical version of that, and kind of play it. I started singing it, and Maggie still singing it. It was around 10:00 that night as we’re putting this show to bed. And this was quite strategic that we decided that we would alert Maggie at the very last possible moment that we were use some of the audio of her singing.

And I sent her a text. Maggie’s been a friend for almost a decade now. I said, “Hey Maggie, just heads up. We’re going to use some of the audio of you singing. It was really great. Just trust me, it works really well.” And of course, she wrote back in a semi-panicked mode. “What? How did this happen? A whole bunch of questions. “Just trust me, it’s going to be great.” And she did, she was great about it.

The next day, wrapped around the beginning of the end of that interview, you could hear Maggie Haberman singing a capella this absolutely beautiful piece of music, absolutely beautifully. It was as memorable as the content of what she said. [Listen about 10 minutes in here.]

I think we’ve done variations on that. I wouldn’t say this is a hugely important part of the show. This sort of authentic, improvised, real moment between colleagues is, I think, just one of the most delightful.

I mean, you can never bone up on all the subjects that we cover on The Daily. And of course, I don’t have to, in the sense that the reporters are the authorities on it and we have such a strong, smart group of producers. But what it forces you to do is to have kind of a whole new way of thinking about storytelling, and a whole new way of processing the stories that we’re telling.

What you can do — and what I think The Daily’s gotten really good at — is sort of being pretty systematic in how we think about a story. Like, where are we going to start a story, where are we going to take that story, where might it end?

We’re hugely open to all the ways in which that can change once we actually get somebody on the phone. And the interview can go in a bunch of different directions. But we’re so rigorous at the front end, at the beginning of a day or of a story, in thinking about where could this story take us. Where will it land? If we have a second segment, how might that speak to the first one? There’s a lot, a lot of rigor.

By 10:15, we’re all meeting in a conference room on the fourth floor here at The Times. We have two options at that point. One is we already know what our show for the next day will be, because it’s something we’re making in advance, it’s already somewhat made, or it’s about to be made that day. Or — in the vast majority of cases — we’re making a live show from scratch.

Then we’re going through what’s happening in the day, and figuring out which stories could be a Daily story, which are not a Daily story. What’s right on the bubble, but maybe it’ll be more of a headline at the end of our show.

And then once we pick one or two things, we have a bunch of things we have to do to even get to the point of whether it can happen. Which Times reporter might tell that story, are they available, how are we going to approach it? What kind of sound are we going to introduce beyond the voice of the reporter? What’s the idea that we’re going to get out of this? How’s it going to have impact?

You could categorize these forms in different ways. In the best-case scenario, all those things are happening at the same time. You’re literally having the onion peeled apart in a way that the world has revealed to you and new. And you have an idea in your head at the end that you may not even known existed before. And then it’s all happening with such rich storytelling and sound that you’re feeling it. And I think the combination of those three is the essential DNA of the show.

We would never write a script, we would never draft questions without first talking to the reporter, because there’s just way too much information that they have that we don’t have. So it’s not so much a pre-interview, it’s a brainstorm: Like, what is the story here? How should we think about it? What’s your understanding of it? What’s your idea of what the big idea of this is? And then from there, we start drafting questions.

By the time that’s done, it’s maybe 1:30, 2:00. Could be up to 3:00. We try to do our interviews for the show between 1:00 and 4:00. Now, if I’m going to be honest with you, there have been plenty of times where we can’t do that interview until 5:00, 5:30, 6:00. I mean, there have been breaking news moments where we’ve done these interviews at 9:00 at night.

I think, in a different sphere, that’s what makes Alec Baldwin’s Here’s The Thing work so well, right? He’s talking to other people who are accomplished people, but they are his peers in age, in accomplishment. The fact that these are your colleagues and that you know them is really a major driver of the show, right?

And funny things have happened. I was in Paris once and when I was there, on a whim, I met with my colleague who’s a Paris reporter, who I didn’t know at all, but had a really wonderful time having coffee with him. Fast forward a year later, and he and I are on the phone talking about the French election and Marine Le Pen, and we know each other. It makes a really big difference.

I’ve been here for 11 years and I know all these reporters — some of them I’ve spent weekends on the beach with. Some of them I’ve worked on many, many stories with, and I’ve been in the trenches with them on campaigns. Or in the case of Andrew Sorkin, we co-bylined a lot of merger and acquisition stories about the retail industry in the mid-2000s. When he comes on the show, and we talk, there is a real richness to the rapport that I think you can hear.

I think The Daily taps into that great oral tradition of journalists, enthusiastically talking about a story in a way they’re excited about, and it gets people excited about it.

And the print report is different. I think that’s just a reality. I learned this in a very powerful way. I think after the election of 2016, people questioned the very idea of omniscience and institutional wisdom all over the place. That was an essential factor of the campaign, and it was an essential question of the media afterwards.

And I think The Daily cannot be divorced from the moment of its founding, which is February 2017. After that election, when we all felt that we had absorbed some really profound lessons. It’s complete dedication to listening, to empathetically understanding where people come from. Like, that grew directly out of that campaign.

I wouldn’t say that it was the most natural transition. I mean, there were definitely moments where Lisa, who is an incomparable audio mind, taught me some very invaluable lessons. The one I love the most is her explanation to me that unless the host laughs naturally when he or she wants to laugh, the audience doesn’t quite know they can laugh. You’ve given them permission to laugh. It took me a while to understand that if something funny happens, you need to laugh.

Part of what Lisa has taught me is that I have an instinctive way of talking and affirming people with my sounds, as we call them. And that I could embrace that, but that I had to be conscious of it — but not too conscious of it.

And the other thing is this job requires an incredibly active form of listening. A highly engaged kind of listening. And it took me a while to understand that.

There were moments where I’d look across the table at Lisa, and she would basically be looking at me saying: Don’t look at me. Get in the interview. Stay in the interview. She had a wonderful hand gesture where her two hands would come together and point down to get in there. And that took me a while to understand. Any single moment that you lose, any single moment that I lose my focus, is a moment where I miss something important — I don’t react to it, I don’t process it.

So what I have learned to do — it’s been a really powerful learning experience for me — is that every moment I’m on the phone or in a studio with somebody, I have to be completely focused. It’s hard, but it makes a huge difference.

What I never anticipated was that people would recognize my face. It just feels like a mixed-up use of the medium. In radio, you don’t really think about the way someone looks. But for a variety of reasons, social media being the biggest, people do know what I look like.

And often there’s a line in those emails, and we get a lot of these, that says: I don’t agree with these people — this person, this gun shop owner, this white nationalist — but I finally see them as a person. Or I finally understand where they’re coming from. I finally understand why I disagree with them. I finally understand like what the ideology is about. I finally understand how biography intersects with politics, or something.

And so there was a really powerful note that just got that I wanted to share with you from a person who was 17 years old.

[Here’s that email, FYI.]

To whom it may concern,

I wanted to take a moment and express my gratitude for your excellent journalism, especially in today’s episode of The Daily. I am a loyal listener of the podcast and the episodes are always wonderful, but today’s was so incredibly enlightening that I felt I had to reach out.

After a tragedy such as the shooting in Las Vegas, there are stages of grief that the country goes through: panic, shock, anger, and eventually a glaze over the eyes of America. Through all this, it is difficult to understand why a tragedy such as the death of over 50 people could happen. At this point, no one knows why that man did what he did, but the episode you put out today was a forward step for me in understanding how a tragedy like this could occur. It is easy to become wrapped up in anger at the greed in the history of an institution such as the NRA (which I will admit, I did feel throughout the episode), but I am grateful for your interview with the owner of the gun shop because it reminded me that we are all human. I think that is my favorite part of The Daily: it is a humanizing news outlet. It doesn’t mean we can’t be angry or upset, but it is so important to remember that we are all flawed, regardless of which side of the isle we identify with. I may not agree with the views of everyone who is interviewed, but I love having the space to hear someone out and try to connect to where they’re coming from on a human level.

I am 17 and often I feel frustrated in seeing the world around me and being helpless to understand it or fix it. It is honest reporting like that of the New York Times and others which helps me feel empowered to seek understanding and find ways to help people. I take pride in the fact that I am more politically informed than most adults I know, but that wouldn’t be possible without institutions like yours. I wish I could financially support the NYT, but at this time all I can offer is my support and loyalty. In a country where fake news clouds the vision of many Americans every day, I want to thank you for providing clarity on The Daily.

May God bless you in your pursuit of truth.

The volume of the feedback is really high, and that has blown my mind. There may be an episode we do where we get a hundred or more emails. And when you’re a print reporter, that just doesn’t happen — very, very rarely happens. There’s something about audio, with its intimacy and how people consume it, how they feel when they’re consuming it, and the relationship they have with the show, that registers so personally.

The form of the feedback is so personal. And that has been the most striking part of the feedback: It’s the volume of the feedback and how personal it is. People share a lot about their lives, when and how they consume the show, why it means so much to them, how the content has changed their views. It’s such a nuanced and personal and confessional style of feedback, that it tells us that the show is part of people’s emotional lives.

We often talk about a moment we love. And it may seem hard to know exactly why we love it so much, and I’ll try to explain. We asked Helene Cooper a question on the night that the U.S. began bombing in Syria after Bashar al-Assad’s government was accused of gassing its own people. And dozens of people had died.

And so the president ordered this attack on an air base in Syria. We got on the phone late one night, and she’s an extraordinary guest. She’s an authority on the Pentagon, on the military. She knows her stuff cold. We asked a provocative question, which was, “Are we now at war with Syria?” [Listen about 6:50 in here.]

And she paused. And you could hear the pause. Then she said, “I don’t know.” And we love that answer. It was honest. It would be very hard to imagine [that] in a print story. And this is what I’m talking about. It’s really powerful for the Pentagon reporter from The New York Times to acknowledge what she didn’t know. And then actually, we followed up with her a couple weeks later, and asked her that very same question. By then, I think she had an answer.

I grew up much more watching television interview shows. Whether that was Charlie Rose or Larry King, I don’t know that there’s any kind of a straight line from watching those people to how I was. I think my form of hosting and listening, is the one I practiced as a print reporter for 15 years. I mean, the same mode of listening. It’s just there’s a microphone in front of me and an audience listening.

It’s funny. I don’t listen to a ton of podcasts. I did start to listen to Here’s the Thing about a year before The Run-Up. And I do have to say that I love how much of himself he introduced into those episodes. I mean, take the interview he did with Rosie O’Donnell, or somebody else who grew up on Long Island like him, and how much he wanted to talk about his childhood.

Now, this is a different show, The Daily. And so, it’s not about me. But I value a host who understands that his or her own experience is the eyeballs of a listener. And I think that’s an interesting example. I think the comparisons to Alec Baldwin end there.