“As much as possible, when I know things are happening, I try to hear it or read it for myself first before reading any stories on it…I mean, they all lie in one way or another.”

“It’s important to encourage people to think for themselves, and that’s why we have all these different news outlets. That’s why we have the internet and stuff. People are sick and tired of the same old narrative. These lies have become known. We know that the mainstream media is lying to people.”

“To me, ‘fake news’ is, in a nutshell, people pushing a personal bias as the news.”

“There’s news that’s false. These facts are made up or it’s not fact-checked or whatever, it’s false news. But I also think there’s a version of ‘fake news’ that’s different. Either news media or social media outlets will amplify Trump or his opinion at the expense of real news. It’s taking something like that and using it to fit the anti-Trump narrative…to me, that’s not news.”

“Fox has to be so pro-Trump to a certain extent because all of them are so anti-Trump.”

Going back to the original documents. Thinking for yourself. Fact-checking. In a fascinating and counterintuitive new paper for Data & Society, sociologist Francesca Tripodi writes about how “individuals who describe themselves like Vice President Mike Pence, ‘Christian, a conservative, and a Republican, in that order,’ conceptualize truth.” Tripodi spent months with two groups in Virginia — one of college Republicans, one a Republican women’s group — witnessing how the the types of reading practices learned in Bible study at evangelical megachurches trickle down into how these conservatives read news. Tripodi describes this process as “scriptural inference,” writing, “time and again, respondents described how they were drawing upon the same kinds of skills taught in Bible study to determine if the news they were reading was accurate. They used the inconsistencies between speeches they listened to or read directly and the mainstream media coverage of events to construct a broader argument that sources like CNN, The New York Times, and MSNBC are ‘fake news.'”

When they want to research, where do they go? To a person, it was Google: “When I asked them to explain to me what doing your own research looked like, one hundred percent of the people I spoke with began with a Google query.”

“I believe basically [Google] works as a fact checker,” one student told Tripodi. “I check a couple of those sites and see which ones, which similarities are they sharing together. I more click on the top ones because I know how Google works. It takes stuff that’s really new and relevant, and tries to put it on the top thing.”

But, as Tripodi writes here, “scriptural inference is in turn influencing Google’s results,” and the exact phrase someone types into the search box — “black on white crime” (the Google search that terrorist Dylann Roof claimed shaped his racist beliefs), “NFL ratings down,” etc. — can dramatically affect the information they receive. From the paper:

In my interviews with Sarah, she admitted that her Google searches rarely revealed alternative points of view. However, she did not consider how her returns were tied to her own search practices or Google’s algorithmic ordering of information. Rather, she used her Google returns to validate her claims, as though Google failing to return an alternative perspective meant that one did not exist.

“Even in the face of research and due diligence,” Tripodi writes, “voters can walk away from Google armed with alternative news and alternative facts.”

I spoke with Tripodi about her research, and our conversation, condensed for length and clarity, is below.

As an active audience scholar, I wanted to push back and say, “Well, how are conservative audiences interacting and engaging with media, and what are the meaning-making processes that they are going through?”

I was talking with the lead on [Data & Society’s] media manipulation team, and she said it reminded her a lot of Bible study. I was like, “Oh, I should ask if any of the people in these groups go to Bible study,” and a bunch of them did. So I went to a few Bible studies with a college student, and a few led by one of the participants in the older [group of women]. And I realized that’s how they were applying the deep reading of Bible practices into other spaces.

I’m not saying that all constitutional conservatives even go to Bible study. But this practice of returning to an authoritative text and leveraging your own personal dissection of it, rather than accepting an elitist interpretation of a text, is fundamentally bound to this practice within Protestant evangelical churches.

Part of it is not understanding how your keywords and key searches very drastically change the information that Google sends back to you. And I don’t think that’s necessarily specific to conservatives — but I do think that conservative media producers are exploiting and understanding these practices and are meeting conservatives there.

These searches are just going to be very different depending on whose words you trust. Epistemologically, [liberals and conservatives] are very different — and the way in which Christian conservatives approach the Bible is very different from the way Christian progressives approach the Bible. And you can drill into the Bible and the Bible can say very different things, depending on where you drill in.

I’m trying to demonstrate, through these practices of scriptural inference — we shouldn’t pretend that conservatives aren’t deeply involved in these meaning-making processes. And we shouldn’t assume that these mechanisms can be changed quickly.

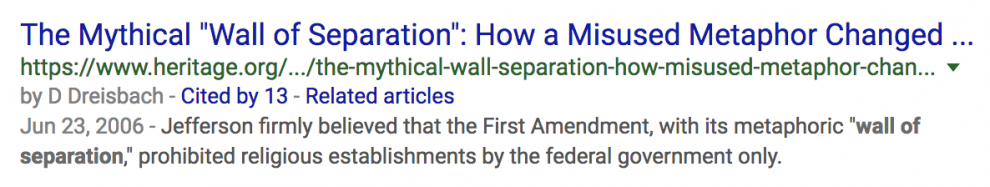

But take the phrase “wall of separation,” for instance. When it comes to the separation of church and state, conservatives very much believe that it’s always been about protecting the church from government encroachment, rather than the other way around. They believe that Christian faith should be intimately connected to government decisions. And they feel that way in part is because this idea of “wall of separation” is from Thomas Jefferson’s letter to the Danbury Baptists: If you read it, it’s supposedly about how the Founding Fathers were going to protect the church from the government.

So if you Google “wall of separation,” the first result will be to the Library of Congress, but soon you get to the Heritage Foundation. Or think about the FBI investigation — framing it as “FBI investigation” versus “FBI spying.”

Conservative media, and our president, are using these same kinds of words. And so if when you Google them, if those are the practices you’ve been taught in terms of how to search your truth and do your own research, then you end up in kind of an ideological circle.

Very small changes in keywords make such a huge difference in the information Google returns. I never would have imagined that adding something as small as “1.4 million” would yield such dramatically different ideological positions. [See pages 31–33 in the report for more behind the example she’s citing here.]

The conservatives specifically in this study — but also more broadly; you can see it in Ted Cruz’s questioning of Mark Zuckerberg during his congressional testimony — are fairly critical of YouTube and of Facebook; they think they are silencing conservative perspectives. There’s no understanding of how other perspectives might also be silenced.

Even more so, though, you have very sophisticated conservative media production companies that are driven by a desire to monetize and increase revenue, and they definitely are exploiting these practices of scriptural inference in the method of search engine optimization. [One section of Tripodi’s paper, not covered in this story, focuses on the right-wing video site PragerU.] They know how to target these audiences, and they’re driving an agenda.

I definitely blame Google for part of it, but I think this way of targeting, flooding a system with keywords, is not just one-sided. These search terms don’t just come out of nowhere.