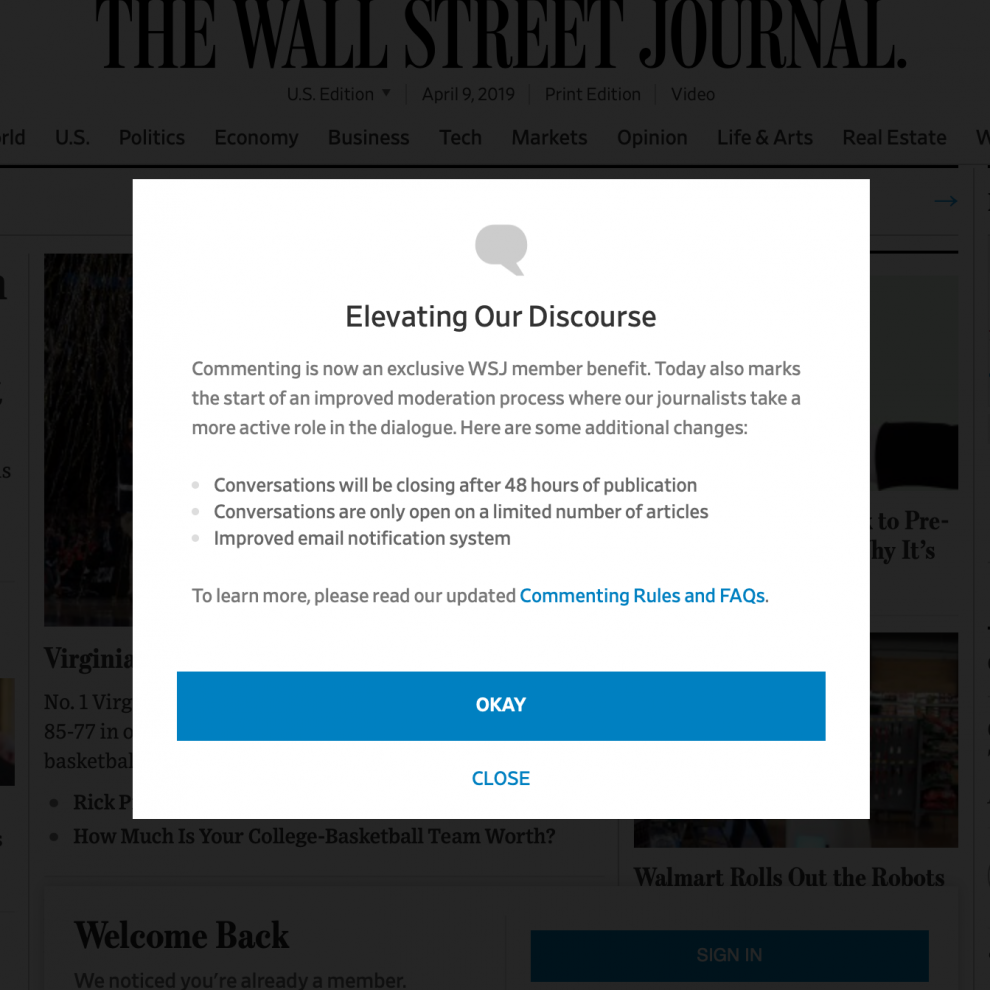

Editor’s note: The Wall Street Journal is making some changes in how it thinks about commenting and conversation on its digital platforms, announced a few hours ago by editor-in-chief Matt Murray. Here, Louise Story, the Journal’s editor of newsroom strategy and interim chief technology and product officer, explains the research and strategy underlying the changes.

Our readers this week will see a lot of changes built around the goal of elevating the quality of community discourse on WSJ.com. It’s a project we’ve been working on for months, starting with rigorous research and ending with a strategy to foster healthy conversations around our coverage. First, a few of the changes:

Last year, as the midterm election approached, web sites of all sorts were seeing increasingly hostile comments posted by their users. In our news coverage, we wrote about some examples, like hate speech on YouTube Super Chats.

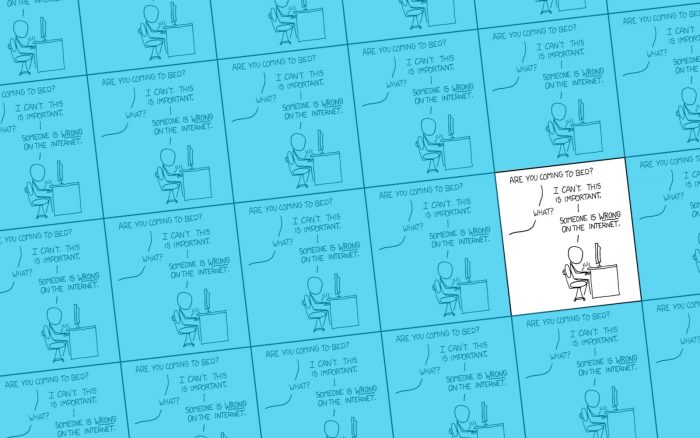

But at some point, we looked at ourselves and asked what we were doing about it. Were we providing a forum for thoughtful conversation? Were we providing an experience that interested most of our audience? Were we leading by example?

We decided we could do more to foster elevated discourse and to welcome broader parts of our audience to join in conversations around our articles. We kicked off a five-month process of in-depth audience research and news product development. It involved everyone from the Journal’s Standards desk, community team and numerous reporters to the product, design, technology, R&D teams, and the membership and customer service desks.

We know there will inevitably be a small group of people who may not like the changes, but there is a far larger group that would like to contribute to audience conversations if the postings became more thoughtful. Here is what we have learned from our research about audience conversation:

From the perspective of heavy commenters:

From the perspective of light commenters:

There are, of course, also tons of non-commenters. In fact, there are also lots of people who subscribe to the Journal and never, ever take a peek at our comments sections.

The comments box and first few comments on one of the first articles open for audience posts under the new system.

One of the concepts you learn in Economics 101 is opportunity cost — which means that when you do one thing, you’re missing out on doing something else. The thing you are missing out on is the opportunity cost. In the case of commenting, we have concluded that overly focusing on the small subset of users who comment frequently and want no one intervening at all in their comments is costing us the opportunity of engaging with our much larger, growing, and diversifying audience.

Indeed, when we looked at the demographics of our heavy commenters, we found they don’t represent the Journal as a whole. That led us to focus on the people who are not commenting as much. Women and younger people have been less represented among our commenters than they are among our subscribers, so we took a look at what was keeping them away. What we heard was they want to feel safe from bullying and share their comments in a forum in which they won’t be attacked. This is important feedback that led us to look at workflow changes that would enable us to better enforce our existing commenting policies.

Some other audience findings shaped our approach. Among them: Most commenters don’t expect to be able to comment on all articles. (Yes, some may, but research found them to be a real minority.) From this insight, we realized we could use our resources better if we picked articles each day for audience conversation, listed them openly for the audience to find and had our moderators spend more time finding great comments and story leads and bringing those into our journalism. In fact, we have reframed the approach so much, that we are not calling our team “moderators”; instead, we are calling them “audience voice reporters.” They will report on the audience conversation.

So where does this leave us? We hope in a place where more people will participate in our audience conversation. Visiting our site should feel like there is more focus on that conversation, even though it’s happening on fewer stories, because we have modules on every article about which stories are open for conversation. And we will be featuring thoughtful audience posts high up in stories in a revolving carousel to capture a variety of perspectives.

Our standards for posts remain the same — and they can be found here — but they will be enforced more than they were. We owe it to our readers and our journalists to lead the way with thoughtful discourse.

Louise Story is editor of newsroom strategy and interim chief technology and product officer at The Wall Street Journal.