Last summer, The Correspondent began signing up ambassadors for its crowdfunding campaign, which aimed to raise $2.5 million in just a month’s time. These ambassadors would be tasked with promoting the expansion of Dutch publication De Correspondent into the U.S. and English and explaining the reasons to support it.

One of the people recruiting ambassadors was The Correspondent’s first U.S. employee, Zainab Shah, and one of the people she reached out to was Mariam Durrani, an anthropologist who teaches at Hamilton College and whose research focuses on Muslim youth.Durrani tentatively agreed. One of the topics she studies is the growth of Islamophobia, something certain news organizations have played a role in. “I’m interested in news media that tries to challenge some of the status quo discourse,” she told me. But before she would commit fully, she said, she wanted more information about what The Correspondent would actually be, beyond a set of appealing principles.

“I was still waiting to hear more substantively about what it was going to do in the U.S.,” she said. “They have no record in the U.S. And as the campaign developed, I thought at some point there would be a teaser, a preview: ‘Here are some of the kinds of stories we’ve been talking to people about.'”

But that substance never came. For Durrani, the organization wasn’t being transparent enough about what it would publish in the U.S. She decided she didn’t have enough information to be a U.S. ambassador, and declined.

The Correspondent’s crowdfunding campaign — which ended up raising $2.6 million — was remarkable for how little indication of what sort of work it would produce. Here’s Emily Bell writing about the successful drive for The Guardian:

Last week, much to the surprise of many (myself included), the team reached its first financing goal of $2.5m to start a newsroom in the US.1 Particularly admirable about the Correspondent’s campaign was that it raised membership without publishing a word. It asked people to buy into the idea of journalism created in a transparent, non-hierarchical way.

Before one gets carried away, it is worth remembering that $2.5m is a tiny amount, even to support non-profit news. And the cynical might argue that it is easier to raise money with a strong campaign than it is with actual journalism that one can more readily evaluate. Nevertheless, it’s a great achievement and a sign that, to capture both the public imagination and cash to support journalism, companies now have to lead with their values and offer transparency in the process.

The Correspondent seemed proud of the whole without-publishing-a-word thing. It retweeted a tweet highlighting the phrase, and cofounder Harald Dunnink quotes it in his how-we-did-it retrospective.

We were asking people to back our principles before the product had even materialized, and we knew how difficult that would be. So we started building a movement well in advance of November 14, 2018 [the day the crowdfunder launched].

Columbia journalism professor and Wall Street Journal veteran Bill Grueskin has made it a running joke on Twitter that no one seems to know what The Correspondent will cover.

Even today — nearly six months after the fundraiser concluded, two years after their “move to the U.S.” was announced with a launch “a year from now,” four years after a cofounder first tweeted about it — it’s still a hard question to answer.

Last week, I emailed cofounders Ernst-Jan Pfauth and Rob Winjberg a set of questions for this story, and one of them asked specifically for “some examples of the stories you plan to run in the English language.” Pfauth’s reply: “Editorial decisions like this we always make in collaboration with correspondents and members, and we will do so in the coming months when working towards our launch in September.”

From The Correspondent’s FAQ.

Even on Tuesday, when The Correspondent issued an apology for mishandling its decision not to have a U.S. newsroom, things weren’t clear. The statement promised The Correspondent would “in the coming weeks” provide “insight into how we plan to offer journalism that is relevant to all our members” and “a detailed description of how we expect our correspondents and editors to work” — but that it would be “taking the time to [do so] carefully and precisely.”

This is a bit of a pattern. Here’s a paragraph from a story we ran back in 2013, before the Dutch De Correspondent had even launched:

De Correspondent has caused quite a stir in Dutch media, and attracted some criticism. Several spoofs were erected; De Verslaggevert (“The Reportert”) raised a total of €90 to spend a year thinking about a business plan and deliver a “completely unknown journalistic surprise.” One prankster made a duplicate of De Correspondent’s website (at decorrespondent.org instead of .nl) which claimed that Wijnberg’s project had been an April Fools’ joke — a social experiment to answer the question “How much money can you raise on empty promises?”

I don’t read Dutch. Most people who write about media in the English-speaking world don’t read Dutch. And while Google Translate is always a click away, that language barrier — along with the fact you need to be a paying member to see a list of recent articles — has kept people from spending time with De Correspondent’s journalism, to see what it produces.

But the best model for what The Correspondent might publish in English is what De Correspondent publishes in Dutch. I thought that a close analysis of the site might provide a window into the type of output new members could expect.

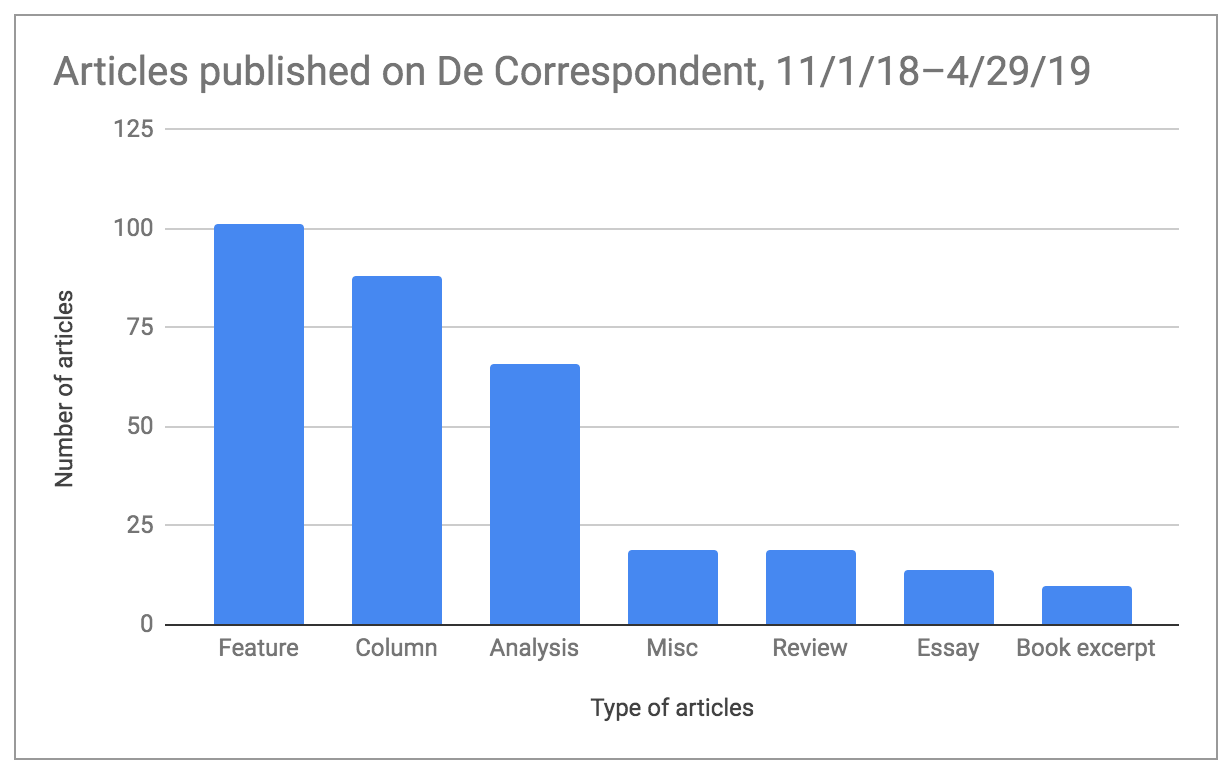

So, with the help of Google Translate, I looked at every article published on De Correspondent’s site over a 180-day period — between November 1, 2018 and April 29, 2019. That was a total of 456 articles — generally between 3 and 5 published per weekday. (Reminder: De Correspondent has a full-time staff of 52 in Amsterdam.)

But a lot of those articles were things like pointers to podcast episodes, link roundups, and promotional posts for things like events or crowdfunding efforts. Once I excluded those, I had a total of 317 articles to work with.

After spending all those hours reading De Correspondent, I grew fond of it. Since the correspondents’ faces are featured at the top of every post, they became familiar over time, even though I was reading them only in translation. The design is nice. The fact that De Correspondent is both ad-free and for-profit is genuinely interesting. And in the instances where reporters reached out directly to readers (more on that below), I saw some promising examples of how that relationship can bear fruit. Also, while I didn’t read every comment closely, De Correspondent has a genuinely active and seemingly troll-free comment section.What I didn’t see, though, was anything revolutionary. Many of the things that I liked about De Correspondent (efforts at reader engagement, reporters’ transparency about how they work, a focus on membership) can also be found in various forms across many American news sites we’ve written about.

And some of the things I dislike about American news coverage are true of De Correspondent, too.

Diversity is severely lacking, as has been pointed out in the Dutch press (more on that below): In the six-month period I looked at, 98 percent of the articles were written by white people. (About 19 percent of the Netherlands is of non-European ethnic origin.)

Nearly twice as many stories were written by men than by women, and the coverage areas tended to fall along stereotypical gender lines as well. Male columnists tackled politics, EU politics, economics, sports, and war — all topics quite prominent on the site — while women covered animals, nature, and family (and those pieces were in shorter supply).

It was disappointing to realize — to actually see in the numbers — that while The Correspondent raised $2.6 million in part by stressing diversity and inclusivity, tapping ambassadors like DeRay Mckesson and Baratunde Thurston, the Dutch site is not a model of that diversity.

I also spoke to several Dutch women of color who asked to remain on background for fear of retribution (the media in The Netherlands is more tight-knit, insular, and male than it is in the U.S., they said, and speaking out previously had brought out Twitter harassment in force) but what I heard repeatedly was that De Correspondent’s problems with diversity had been there since its launch in 2013, that the issue had been raised over the years, that the four white male founders had said in various public forums that they’d do better, and that they hadn’t, really.

I saw that a lot of people are disappointed with the new Correspondent apology and I just wanted to say: any media analyst from outside The Netherlands trying to understand what is going on should probably look at the way Dutch culture operates vis a vis white powerful men

— Flavia Dzodan (@redlightvoices) May 1, 2019

I also asked about diversity issues in my emailed questions to Wijnberg and Pfauth last week. Pfauth’s reply: “Our diversity strategy hasn’t changed: we seek global diversity in our team. We want to collaborate with correspondents and members from all over the world — including the U.S. — to cover the greatest challenges of our time.”

This is what I found. You can see my spreadsheet here.

I grouped each of the 317 articles into one of seven categories, using my best judgment. Those categories are:

As you can see, features are the largest single segment, and they’re substantial stories, averaging about 2,800 words. But columns and analysis together, each relatively light on original reporting, make up a larger share.

Here’s the breakdown of the type of articles published:

Gender diversity: Men had roughly twice as many bylines as women; just 31 percent of all articles were written solely by women. If you count bylines rather than articles — because some articles have more than one byline — 34 percent of bylines were from women.

That second byline-counting method is the one used by the Women’s Media Center in its annual look at byline diversity. If De Correspondent had been one of the news organizations this year’s report analyzed, it would have finished 8th out of 9 in women’s representation: behind HuffPost, MSNBC, Vox, CNN, Fox News, The Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times. (It edges out The New York Times by 1 percentage point.)

Men got 55 percent of the bylines on features and 72 percent on columns. Columns were generally about Dutch or EU politics.

Ethnic and racial diversity: 98 percent of De Correspondent’s articles over the past six months were written by white people. A total of five stories were either written solely by a person of color or included a person of color in the byline. Of those five, two were written by the same reporter, two were written by black freelance journalists, and one had a joint byline between a white reporter and a black freelancer. (I should note it’s possible I’m surmising someone’s race incorrectly; this obviously isn’t foolproof, and doesn’t take ethnicity into account.)

The extreme whiteness of De Correspondent’s output is a striking contrast to the way it marketed The Correspondent in the United States. Its launch video puts Mckesson, the Black Lives Matter activist, front and center in the thumbnail. The first person on screen is How to Be Black author Baratunde Thurston (who has since apologized to anyone who felt “duped or disappointed” by The Correspondent’s decision to have no U.S. newsroom). After cofounder Wijnberg appears next, we see Zainab Shah (who has since described that decision as “a betrayal…we had raised funds on false pretense”).

In all, people of color are on screen for 60 percent of the video’s first 45 seconds, with Mckesson, Thurston, and Shah all talking about being underrepresented in media alongside b-roll of African Americans walking outside a South Carolina barbershop and dribbling a basketball outside a Chicago corner store.

“The stories I grew up with about people who looked like me made me feel bad about being me. That story, of all that negativity, is infectious.” “You’re like: I’m not here.” “Where am I? How come I can’t see myself?”

On The Correspondent’s about page, a grid of supporters and ambassadors is half white, half people of color.

so my first question to you is how diverse will the staff be? are native black americans involved in this project at all?

— Daryl Seaton (@redsroom3) November 26, 2018

Thanks for the q, Daryl! We're deeply committed to diversity. It's one of the reasons 'being as inclusive as possible' is a founding principle. @zainabshah is our first US hire and we'll continue to bring in sharp, diverse minds once we reach our $2.5M funding goal.

— The Correspondent (@The_Corres) November 26, 2018

thanks for the response. how do you define diversity exactly?

good luck with your funding goal.— Daryl Seaton (@redsroom3) November 26, 2018

Hi again, Daryl. Diversity as defined by race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, disability, and worldview.

— The Correspondent (@The_Corres) November 26, 2018

Criticism about diversity, racial and otherwise, is also not new for De Correspondent.

That 2013 piece we ran pre-launch noted that “one prevalent point of critique was that Wijnberg’s correspondents were an elitist club of celebrity journalists.” In 2014, in a piece marking the site’s one-year anniversary, editor Karel Smouter acknowledged (in Dutch) criticism that “we have been too white” and said De Correspondent was committed to seeking new voices “outside our comfort zones” and “outside our own ‘circles.'”

On the day the campaign for The Correspondent launched in November, Flavia Dzodan, a feminist and writer based in Amsterdam, tweeted about the gap between its rhetoric and hiring practices when it comes to diversity.

I love that The Correspondent is trying to build credibility in the US by trying to attract PoC but someone should ask them how they treat PoC in The Netherlands: how many they employ & what their writers think of "identity politics" (hint: that they use such naming says enough)

— Flavia Dzodan (@redlightvoices) November 14, 2018

and now they are using all these US big names to crowdfund 2.5 million dollars in the US. Someone should ask how many Black people they have in the payroll in The Netherlands AND how many people who actually have similar ideas to DeRay.

— Flavia Dzodan (@redlightvoices) November 14, 2018

In the six months of articles I looked at, I saw at least one decrying the “identity politics” that Dzodan describes. From that article: “The strange thing is that many writers can get angry about side issues. Such as identity politics…As soon as you hear the word ‘diversity,’ alarm bells must always ring. Nine out of ten times diversity is interpreted very narrowly.”

In a Medium post in response to Dzodan (though it didn’t mention her specifically), Wijnberg said the company needs to do better and noted, “We have also hired staff of color in non-editorial (management) positions and improved the gender balance in key leadership positions. De Correspondent’s two editors-in-chief and our publisher are women.”

Wijnberg to Leendert van der Valk, a reporter from De Groene Amsterdammer who was with The Correspondent team at the time and is now writing a book on De Correspondent: “You never have enough diversity. That is difficult in this discussion, which statistics would critics be satisfied with?”

We very much agree with the need for more diversity, Flavia. We see our international expansion as part of our approach to making that happen. And we have made strides in NL as well thanks to criticisms like this. I wrote more on our efforts here: https://t.co/LUqRgXUT2R

— Rob Wijnberg (@robwijnberg) November 26, 2018

Beyond diversity issues, two elements I was looking for most in De Correspondent were to what extent they engaged readers in the reporting process and to what extent their stories were specifically about The Netherlands. (In the debate over what The Correspondent was promised to be, one element is to what extent should we think of the sibling sites as being defined by nations — a Netherlands site and a United States site — or by language — a Dutch-language site and an English-language site.)

On the first point, only 12 percent of the articles I read either explicitly solicited or specifically mentioned some sort of reader contribution or participation. I tried to be generous when categorizing this and included general calls for comment. When a reporter asked readers if they knew of second-hand clothing stores, for instance, or included a phrase like “I prefer to ask these questions in conversation with you,” I counted it.

In a few cases, reporters involved readers quite directly. This was highly reporter-dependent: Thalia Verkade, a reporter who covers mobility and city life, included reader feedback or participation in almost all of her stories in a series on traffic safety in The Netherlands. Smouter brought readers together online to debate tourism, then wrote about the experience and what he learned. But the vast majority of De Correspondent’s stories don’t seem to involve reader engagement in any particular way beyond the norm.

De Correspondent does have very active comments sections, with many posts receiving hundreds of comments. It has a “conversations editor” whose job is to interact with readers and help incorporate their feedback and expertise.

On national focus, 43 percent of the articles I looked at were clearly Netherlands-specific, focusing on topics like Dutch politics, Dutch soccer teams, and the Dutch provinces. One ongoing series focuses on people who live permanently at Dutch holiday parks, which are sort of like campsites or trailer parks; it’s an impressive series with a lot of original reporting and photography.

Another 17 percent of the articles focused on the European Union (Brexit, Europe-specific migration, and so on).

The remaining articles I looked at were thematic and not strictly tied to one region. I liked De Correspondent’s ongoing focus on climate change and environmental harms caused by the clothing industry, and the coverage around themes like aging. But the heart of the site — the place I repeatedly saw journalism that was memorable and creative, even after being put through the ringer of Google Translate — was coverage of The Netherlands.

One of De Correspondent’s founding principles is that reporters shouldn’t be objective. Not only is that not possible, it’s not desirable. Wijnberg wrote last year:

Journalism is moral through and through, and it’s supposed to be. It’s about what we as human beings, as citizens, as a society consider important, valuable, and relevant — or should consider as such. All good journalism, then, begins and ends with a set of deeply held ideas and beliefs — beliefs about good and evil, about what is just and unjust, about what is relevant and trivial, and about what is true and false.

If you order journalists to check their moral judgments at the door, one of two things will happen. Either they’ll have no clue what to report on and go home without a story, or they’ll figure it out in the only other way possible: by adhering to a silent consensus of what the news should be, determined by others who set the news agenda.

I happen to agree with De Correspondent on this. Does my analysis of De Correspondent include a spreadsheet? Sure, but, as we should all know by now, that isn’t a guarantee that it’s scientific or unbaiased. My take on the site, even my collection of data, is doubtless shaped by my own worldview, which actually matches well with De Correspondent’s stated founding principles: I believe that newsrooms need to be diverse and that, rather than adhering to outdated “objectivity” standards, reporters should state exactly where they are coming from — and then be clear when they change their minds.

So let me do that now. I went into reporting on De Correspondent without a pre-existing opinion on the site; like most journalists in America, I had no idea what kind of content it ran, and had only a vague notion that we should overall be supportive of it. When I interviewed Rob Wijnberg and he told me this wasn’t a story, it made me want to keep going. Through my reporting, I came to believe that the Dutch women who have been telling us for years that De Correspondent isn’t what it seems are right.