You would need five cramped Priuses to carry all the Democrats currently running for president. Four years ago, you would have needed six Ford F-150s to carry all the Republicans running for president. (Okay, three if you upgrade to the SuperCrew.) It seems as if these supersized fields of candidates are the new normal; maybe in 2024 the out-of-power party can be the first to hit three dozen.

Meanwhile, at the local level, it’s often getting harder to find anyone willing to run for office. A Rice study found that 60 percent of all the 2016 mayoral elections they looked at featured just one candidate running unopposed — a number that’s been on the rise since 2000.

And both of these seemingly contradictory phenomena are, at some level, the media’s fault.

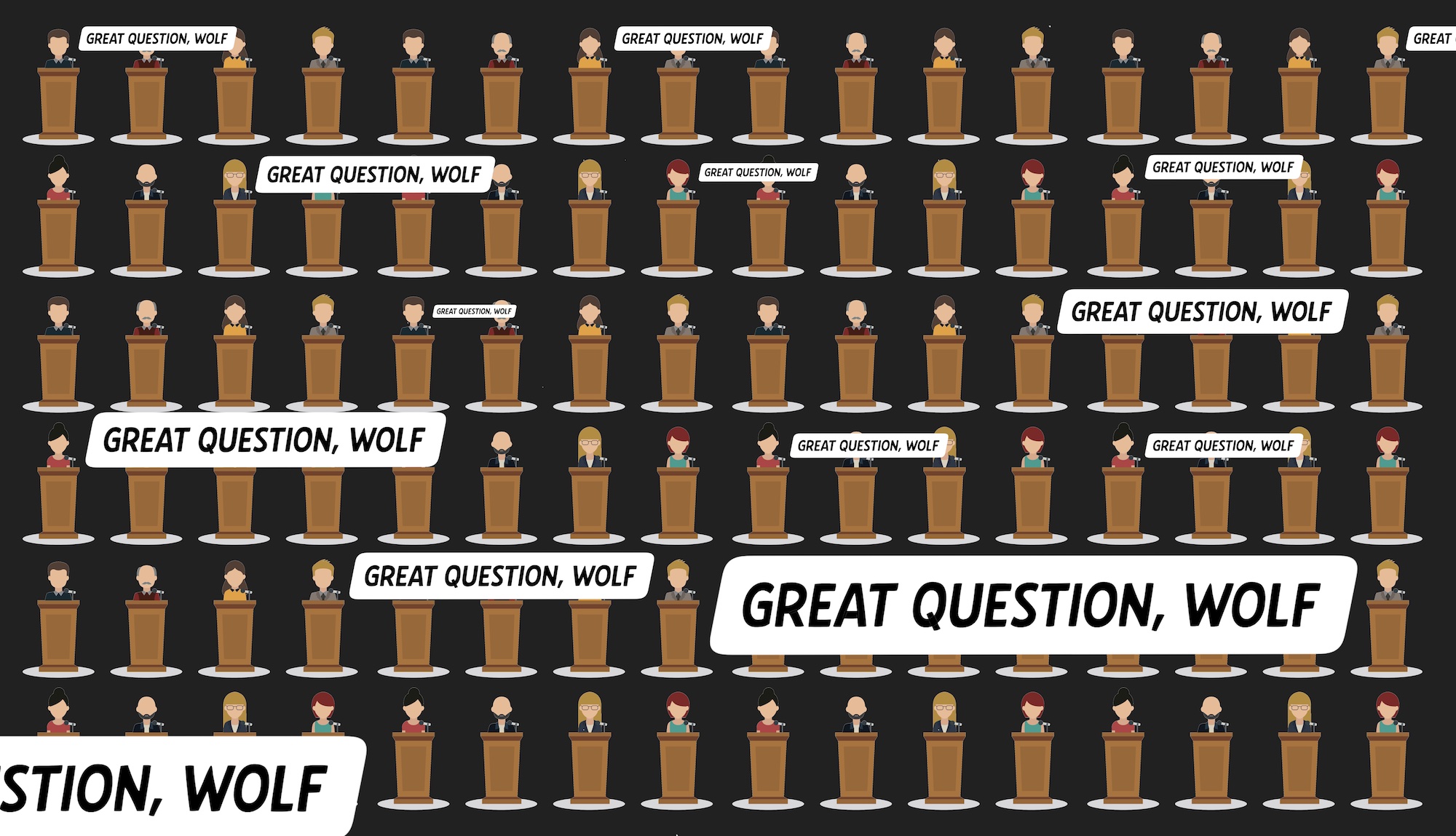

Florida State political science professor Hans Hassell has a piece out today at The Conversation outlining the reasons for those clown-car presidential primary fields, and a big one is the media:

I study political parties and their role in electoral politics. And I believe the rise in the number of presidential candidates in recent years results from divisions within the party coalitions and from easier access to vital campaign resources — money and media — that were not present in previous election cycles…

In the past, candidates were reliant on the media to publicize their candidacy and get their message to voters. Party leaders and elites consistently have better connections with the media establishment and use those connections to promote preferred candidates.

But today’s media environment allows candidates to bring their message directly to voters. Social media bypasses reporters and editors and those who have connections to them so more candidates have easier access to this key campaign resource…

Now, a run for higher office can be a means to other opportunities outside of politics. Republican Sen. Rick Santorum, a presidential candidate in 2016 and 2012, became a pundit on CNN. Another candidate, the GOP’s 2008 vice presidential nominee Sarah Palin, ended up with a show on cable news.

While parties still pressure candidates to withdraw, candidates may be less responsive than in the past. That’s because they care less about the desires of party elites since they may not be as interested in a career in party politics.

So Hassell is pointing to a couple of different factors here. One is that a job in TV punditry can be a pretty decent runner-up prize for an election also-ran. (Though that’s surely also true for corporate boards, think-tank affiliations, and any number of other gigs made easier to obtain with a high media profile.) The other is that the small-d democratization of media has made the editorial bottlenecks of a few top news organizations less critical to gaining momentum; Andrew Yang will probably end up on a debate stage this summer that he wouldn’t have were it not for Twitter, Reddit, and wherever else the #YangGang hangs out. Particularly as Twitter strengthens its position as the place where journalistic conventional wisdom is born, open platforms encourage a broader set of candidates.

But I’d add a third, which is that the Internet’s fundamental delocalization of media has pushed a far higher share of journalistic resources into covering presidential politics than ever before. Among newspapers, the clear winners in the digital transition are The New York Times and The Washington Post, national papers that attract a national audience with national stories. The clear losers are, well, all the local papers cutting their way to profit. The flip side of that shift is that having fewer local resources means less interest in local politics and government. We saw this last month, when new research found a direct connection between the size of a local newspaper’s newsroom and the number of people who decided to run for mayor. More reporters, more candidates.Newspapers have faced extreme challenges in recent years due to declining circulation and advertising revenue. This has resulted in newspaper closures, staff cuts, and dramatic changes to the ways many newspapers cover local government, among other topics.

This article argues that the loss of professional expertise in coverage of local government has negative consequences for the quality of city politics because citizens become less informed about local policies and elections.

We test our theory using an original data set that matches 11 local newspapers in California to the municipalities they cover. The data show that cities served by newspapers with relatively sharp declines in newsroom staffing had, on average, significantly reduced political competition in mayoral races.

We also find suggestive evidence that lower staffing levels are associated with lower voter turnout.

Other studies have found similiar results, that the closure of a newspaper leads to fewer candidates and fewer voters in local elections.

To put this all in the most basic terms: The Internet makes us more interested in national politics and less interested in local politics. That’s in part because we have easier access to national news outlets now, and in part because it’s a lot easier for news organizations to make money covering national races rather than local ones. That higher national interest, in turn, makes it easier (and more career-enhancing) to run for president. And that lowered local interest makes it harder to find someone to run for city council.

If you want to eyeball one version of this phenomenon, look at this chart (via UVA’s Center for Politics) that compares turnout in U.S. presidential elections (inherently a national story) versus midterm years, when it’s local members of Congress who are on the ballot. You can see that, as the media shifts toward digital, the gap between the two increases.

For the 1972 to 2000 presidential elections, voter turnout was on average 15.2 percentage points higher than in the midterm elections two years later. But for the 2004 to 2012 elections, that gap grew to an average of 20.7 percentage points.

Careful readers have already spotted that that chart stops in 2016. Didn’t we have midterms in 2018, with record turnout? Yes, indeed — and it was also the most nationalized midterm cycle in a century, centered on Donald Trump. (“I’m not on the ticket, but I am on the ticket, because this is also a referendum about me,” Trump told rallygoers. “I want you to vote. Pretend I’m on the ballot.”)

A record 72 percent of voters said party control of the House and Senate was a factor in their choice. (That number has been climbing in midterm cycles since 1998: from 46 to 48 to 61 to 62 to 62.) Of the six Senate seats that changed parties, five of them switched to the party that had won that state in 2016. And 2016 was itself an election in which every state’s Senate race went to the same party as its presidential race.

Tip O’Neil — “all politics is local” — is turning over in his grave.

While the new media environment certainly isn’t the only factor in getting voters excited and candidates interested — it’s a pretty big one. Networks, news sites, and social platforms are collectively pretty good at directing people’s attention. And increasingly it’s being directed straight at Washington — especially 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.