Welcome to Hot Pod, a newsletter about podcasts. This is issue 214, published June 18, 2019.

Mary Meeker presented the 2019 edition of her Internet Trends report at the Code Conference last week, and podcasting pops up for a slide, grouped together with smart speakers as part of the broader voice trend.You can find the whole deck here. I’d recommend checking out the Nieman Lab and Recode writeups. Turns out American adults spend a daily average of around six hours on digital media these days. My burnt-out eyes, I would never have known.

Speaking of Vox: Vox Media has ratified its first collective bargaining agreement with the Writer’s Guild of America, East. You can view the (rather impressive!) terms here. I imagine this development has some ramifications for the process at Gimlet Media (brought to you by Spotify), which is also organizing through WGA East.

Audiobooks are not exempt. There’s no news peg to this piece, other than the fact it’s based off a keynote I gave earlier this month at the Audiobook Publishers Association Conference in New York. I took the keynote invite as an opportunity to revisit the subject of audiobooks — from which I had shifted my attention away since last summer’s shakeup of the Audible Originals team, though maybe I shouldn’t have — and think through its current relationship with the podcast world, whatever that may be. This piece isn’t quite that keynote, because a bunch of the ideas contained within has been revised, so if you were there at the Javits Center, sorry, it’s all different now.

The question I wanted to probe: How will the ongoing formation of the podcast industry affect the digital audiobook industry?

One could argue that perhaps there wasn’t really much of an effect at all; that the industries are separate, parallel, and mostly unintrusive of each other. The audiobook industry has been booming for a while now, with the digital audiobook market experiencing double-digit annual growth over the past decade. And that growth trajectory appears to track alongside a similar arc for podcasting across the same period.

Sure, audiobooks remains a modest revenue segment of overall book publishing business compared to print and ebooks. A recent Association of American Publishers (AAP) report, cited by Publishers Perspectives, noted that “downloaded audio” makes up 10.5 percent of book sales through online retail channels, while the print format is pegged at 43.2 percent and ebooks at 27 percent. But the more pertinent point is that digital audiobooks are rapidly growing as a segment compared to other book formats, some of which are even in decline. According to another AAP report, digital audiobooks, recorded as “digital downloads,” grew by a whopping 36.4 percent between the first halves of 2017 and 2018. In contrast, hardback and paperback revenues grew by 7.2 percent and 2.6 percent respectively, while ebooks shrank by 5 percent. (Notably, physical audiobook revenues declined by 19.9 percent, which makes sense, because CDs. On a separate note: Do book publishers release audiobooks as vinyl?)

There’s a similarity that can be drawn between the narratives of audiobooks and podcasts. Both are small but rapidly growing segments of their respective home ecosystems — book publishing in the case of audiobooks, radio in the case of podcasts — at a time when many other parts of those industries appear to be flattening out. There are key differences, of course, most crucially the fact that digital audiobooks largely grew over the past decade under the auspices of one particularly active dominant platform — Audible, a.k.a. Amazon — while podcasting largely grew during the same period under a relatively benign dominant platform, Apple.

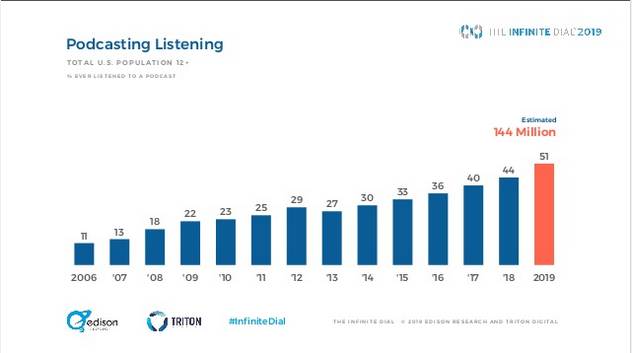

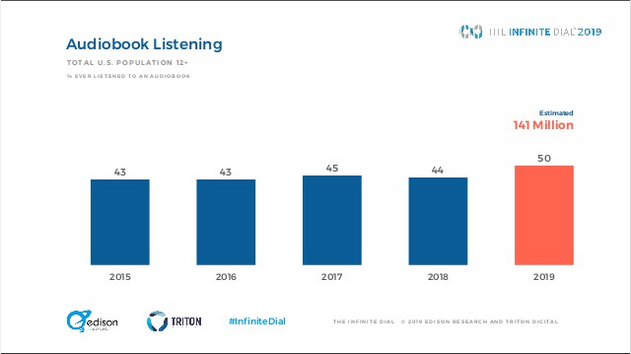

If anything, the relationship between audiobooks and podcasts is probably a mutually beneficial one. In the most recent Infinite Dial report, Edison Research observed that “along with the increases in podcast listening, audiobook consumption has also increased, indicating a trend towards increased spoken word audio consumption.” That observation comes from the finding that both audiobook listening and podcast listening had experienced similar growths between 2018 and 2019.

Here are the relevant slides:

There’s a straightforward interpretation that can be made here: Podcasts are helping more people develop an affinity for spoken audio content, prompting those humans to then turn to other forms of spoken audio content, like audiobooks, to satiate that newfound hunger. The same probably goes for the other direction, from audiobooks to podcasts. And so here we are presented with an optimistic view of the future: It’s all audio, it’s all on-demand digital audio, and it’s all boats being lifted by the same rising tide.

That may well be true, but only if the structural conditions of the competitive landscape — namely, how the mediums relate to each other in terms of how they think about audiences, suppliers, and distribution chain — remain the same. But, I mean, come on. What are the odds of that happening?

To frame it in the form of a question: Will these different digital audio worlds continue to exist separate, parallel, and mostly unintrusive of each other? Or will they, over the medium to long term, end up colliding in direct competition?

This is probably a good time to bring up the platforms, the fundamental arbiters and gatekeepers of our modern media universe. Audible, of course, which already accounts for about 41 percent of U.S. audiobook unit sales (per The Wall Street Journal), but also Spotify, which might seem like a non sequitur but really isn’t.

Here’s why I’m grouping the two companies together here: In case you’ve somehow forgotten, since February, Spotify has spent several hundred million dollars acquiring three podcast companies in accordance to its new grand ambition to become an all-consuming audio platform. Podcasting is the headlining subject in this corporate narrative thrust, but in terms of Spotify’s overarching ambitions, it’s only part of the equation.

In a Freakonomics Radio interview last month, Spotify CEO Daniel Ek popped up to talk about the company and its origin myth, and at one point, he spoke about the various experiences that led the company down the “diversifying away from music” path, offering up a telling anecdote:

We started seeing, in my home country Sweden actually, record companies buying podcasts and uploading them to the platform as another revenue opportunity for them to grow. And it resonated really well with listeners. And that was like the first step.

And then in Germany, record companies there had massive amounts of rights to audiobooks, which I wasn’t aware of. And they started uploading that to the service and very, very quickly, we went from like no listening to that and now we’re probably if not the biggest, the second-biggest audiobook service in Germany. And this is without our involvement. You know, this just happened by proxy of us being a platform. So we started seeing it resonating really well into people’s lives. And they thought of Spotify not just as a music service but as a service where they can find audio. And it played really well into our strategy of ubiquity — i.e., being on all of these different devices in your home, whether it’s the Alexas or TV screens or in your cars or whatever as just another source where you could play your audio.

Two things to pull from this. First, if I were a betting man, I’d sprinkle some action on the notion that there will come a time not too far into the future when Spotify will begin looking into securing audiobook distribution rights here in the United States. After all, the audiobook category falls directly into Spotify’s underlying interests in becoming a ubiquitous, all-consuming audio platform, which would involve expanding into other on-demand audio markets, audiobooks included. Sure, the cost of acquiring audiobook rights would be more expensive than the costs of collecting podcast assets (for now, anyway, on both sides of the equation), and Spotify would have to figure out how to move audiobooks beyond unit sales economics towards streaming economics. But I wouldn’t discount just how appealing a true second option might be for audiobook publishers operating in the age of Audible — especially when Audible is looking to bypass publishers in all sorts of ways.

Audiobook publishers would need to weigh out the balance, though, and that brings me to the second takeaway, which is somewhat waftier. Should Spotify’s diversification gambit work out, the shift could well produce a digital audio environment where many different forms of digital audio content — podcasts, music, maybe even audiobooks — will become more blended together than ever before, which would bring significant ramifications for both audiences and publishers.

In the minds of consumers, this blending may translate to the flattening of various digital audio experiences. By virtue of the way most people navigate media choices over platforms these days, there is a possible future in which digital audio consumers, or at least primary Spotify users, won’t end up being particularly concerned if something is an “audiobook” or a “podcast” or an “audio file with sounds of people doing stuff.” When they pull up the Spotify app to fill up their time, it’s just a wall of mildly differentiated audio content, not unlike the wall that hits you when you pull up Netflix on your Roku or whatever. (The underlying principle here being: The bucket matters as much, if not more, than what’s stored in it.)

[Spotify’s just announced Your Daily Drive playlist — which offers commuters a mix of music and news for their trek into work and is mentioned below — would fit nicely into the idea of Spotify-as-format-intermingler. —Ed.]

How would that flattening impact the life of the audiobook publisher? I reckon audiobook publishers would then find themselves up against the same tenor of competition that magazines and newspapers face these days in the age of Facebook, Google, and whatever’s left of the blogosphere. In the past, audiobooks and podcasts may have indirectly competed with each other as separate and distinct media universes, but the fundamental check and balance there was that each had their own distinct consumer systems. There were structural, habituating things ensuring that it is a specific kind of experience to consume podcasts, just as it is a specific kind of experience to consume audiobooks. However, should Spotify 2.0 successfully mix those two worlds within the same platform, the terms of those specificities no longer hold, In that future, audiobooks participate in a significantly broader horizon of competition, but within a much narrower context.

It should be noted that Audible is also in the middle of a similar kind of mixing. Longtime readers will remember a time not too long ago when Audible’s Originals strategy, then led by NPR vet Eric Nuzum, could reasonably be discussed within the same conversation as podcasting. That originals strategy has since changed, following an executive shuffle in late 2017 and a subsequent team restructure/layoffs in the summer of 2018. And while it seemed like the change was a doubling-down on the company’s mastery of the book publishing supply chain, Audible’s various efforts over the past year suggest something else. Something broader.

There are, of course, all the direct deals the platform has been signing with authors to create audiobook-only products or audiobook-first publishing scenarios. But you also have its growing relationships with content companies — like its deal with Broadway Video to produce long-form scripted comedy originals, including a project by Saturday Night Live’s Kate McKinnon, as well its deal with Reese Witherspoon’s Hello Sunshine to make “audio content that’s longer than podcasts, but shorter than audio books,” per TechCrunch. Also worth tracking: its deepening pipeline into the theater world, now a couple of years old.

There was a time when it was appropriate to think of Audible as an “audiobook publishing” platform and of Spotify as an “on-demand audio everything else” platform. But with all these pieces in front of us, perhaps that assessment was never quite correct. As we move forward in time, it increasingly feels like Audible and Spotify are growing more connected to each other as part of the same ecosystem — which means that audiobooks, as with all other forms of audio media, are not exempt from what’s been going on.

This week in Spotify. The Spotify beat is buzzing. In the recent weeks, we’ve seen the release of a spinoff app, a new personalized playlist called “Your Daily Drive” that’s meant to reconstruct the morning commute listening experience, the rollout of a library redesign for premium users that emphasizes podcast discovery, and a few exclusive content partnership announcements (see the Obamas, also Rob Riggle).

It’s a whole lot of press releases, and that’s probably the point. We’ll see how the actual business shakes out from these moves, but for now, when you get the opportunity to drive some headlines, you do it, I suppose.

Don’t forget to look around the corners, though. Two things that caught my eye:

(1) This little development, first written up by The Drum, which is perhaps the most important piece of the puzzle: “Spotify now lets advertisers target podcast listeners.” According to the writeup, the advertising tool is rolling out in select markets, and two brands, Samsung and 3M, are already onboard for the test.

Two things. First, and as always, it’s worth reiterating that Spotify’s whole initiative around building podcast inventory and growing podcast listening on-platform is a means to an end — the end being revenue, of course. And second, the advertising side of Spotify’s business is a means of a kind. Last March, Spotify CFO Barry McCarthy told investors: “The ad-supported service is also a subsidy program that offsets the cost of new-user acquisition” — acquisition into paid subscriptions, of course. (That quote pops up in Meeker’s report, interestingly enough.)

(2) Water and Music’s Cherie Hu flagged this on Twitter: Spotify recently published a job posting up for a producer to work the end-to-end production of the company’s upcoming “internal News-focused podcasts.” The official job posting isn’t up anymore, but you can still spot the details here. It’s, uh, a lot for a single job.

Speaking of news podcasts on Spotify, what do you suppose is the thinking around NPR’s hourly news briefing appearing on the “Your Daily Drive” playlist? I’m sure it’s all still tentative for now, and of course, it’s good and important for NPR to experiment and try stuff out. But I do hope the public radio mothership is actively working through with the implications of successfully riding Spotify as a direct digital highway to listeners. Particularly as they pertain to the local public radio station system, otherwise known as one of the last bastions of local news that people keep saying is in trouble and needs saving, which doesn’t seem to factor into the “Your Daily Drive” playlist whatsoever at the moment. The same deal can be applied to smart speakers to some extent, I think.

Again, it’s all early days. But if I was station head, I imagine I’d be wary AF. How does my geographically-bounded station fit — strategically, logistically, creatively — into the NPR’s arrangement with Spotify, and whatever platform comes next? More broadly, what are the risk ramifications of lending public radio’s nonprofit journalistic power to a centralizing profit-seeking entity? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

In Ireland, a collective plays the waiting game [by Caroline Crampton]. The place where I live, in the northwest of England, often feels closer to Ireland than it does to London. My city, Liverpool, has lots of historic, cultural, and family ties that visibly cut across the Irish Sea. For instance: A few months ago, Ireland’s national broadcaster, RTÉ, aired an excerpt of a podcast I had produced. At a gathering later that week, half a dozen people came up to me to say “I heard you on the radio!” in a way I’ve never experienced with a British transmission.

Irish podcasts have also long been a fixture in my regular listening rotation, and many of the shows I enjoy come from the same podcast collective: Headstuff, founded in Dublin in 2014. Five years in, the organization — which originally started out as a culture website — is expanding into new premises and developing a membership scheme that includes access to their studio space and editors. At the moment, they have two full-time employees, a full-time intern on a short contract, and three freelancers, and they hope to grow the employee headcount in the near future.

Although Ireland’s population is small — just under 5 million people compared to the U.K.’s 66 million — a Reuters Institute report from 2018 put the proportion of people who had accessed a podcast in the last month at 38 percent, way ahead of the U.K.’s 18 percent. Given this, I was intrigued by Headstuff’s new adventures and reached out to founder Alan Bennett to find out more.

Their business model has always relied in part on the editorial shows that Headstuff supports, such as the popular comedy podcast Dubland and the Irish language show Motherfoclóir, in part on branded projects, and in part on studio hire and production support. When I spoke to Bennett last month, he told me Headstuff’s podcast portfolio currently numbers around 50 shows, which collectively attract around 200,000 listeners a month.

Now they’ve taken over and refurbished the former Westland Studios building in central Dublin, a large music recording studio that has hosted artists like U2 and Bob Dylan. Headstuff has converted its one large space into four studios, including one for video and one aimed at solo or voiceover work.

The idea is partly to accommodate all their current clients who want more studio time, but it’s also driven in part by a “if we build it, they will come” sensibility, Bennett said. In addition to the corporate clients they work with, the space is meant to also be accessible to hobbyists and amateurs, who as members can buy an allowance of credits to spend on studio time or editing support for an annual subscription of around €600 (approximately $675). “There’ll be a members’ area with a little cafe, where they can come and work and have free tea and coffee, meet guests, work on their podcasts, and generally enjoy the space,” he added.

This move into brick and mortar is a big shift from Headstuff’s origins as a culture site publishing essays and reviews. When the site launched its flagship podcast, “it grew in a way that I wasn’t quite expecting,” which gave Bennett the idea of inviting other shows in and forming the collective. Initially, the podcasts that Headstuff hosted and supported worked together just on a cross-promotional basis, but now some have sponsors, crowdfunding campaigns, and live performance operations as well. Bennett also has ambitions to add an in-house sales team at some point in the future.

“Some of our podcasts have been more successful than others at getting sponsors…We haven’t consistently had sponsors,” he said. “I feel like the Irish advertising market hasn’t quite caught up to podcasting yet and there is nobody really putting a lot into it for an extended period of time. So it’s a bit hit-and-miss at the moment, but I think it will get there at some point.”

To date, they’ve done deals with beverage companies like Kopparberg as well as major beauty brands, and Bennett feels that Headstuff is well positioned in the Irish market for when bigger, more confident advertisers do show up. In the meantime, Patreon, studio hire fees, and the membership scheme help to fill in the gaps: “We’re still playing waiting game a little bit, but I’m also trying to force the issue — we’re trying to educate people.”

The long-term goal, beyond making a success of their new space, is to be able to work on bigger, more ambitious productions. The vast majority of the podcasts that Headstuff currently puts out are conversational or semi-scripted, and Bennett has plans to make “for want of a better word, the Irish Serial.”

He added: “To be able to put a lot of resources into it into a show and be able to work on it for months before it comes out, and make journalistic shows or investigative shows or even very highly produced narrative shows — we want to do that.”

They actually have an investigative project already well under way, but the lack of resources has meant progress is slow. “It’s taken so long and we don’t have the resources to move it along quicker,” Bennett said. “We’ve been close to being able to be finished with it for such a long time that, you know, at a certain point it becomes frustrating as opposed to exciting.” The hope is that the new space and revenue stream from it will help to speed things up.

Bennett is optimistic about future growth in Irish podcasting, though, and Headstuff’s role in it as more people get involved. “I think that the appetite is there. Irish people, as the stereotype goes, are a nation of storytellers. And they always like to talk and I think podcasting gives people the ability and the flexibility to do that on a slightly bigger scale.” He hopes that the new Headstuff space, to be known as “The Podcast Studios,” will make starting a high-quality show more accessible and affordable for newcomers to the medium, and help existing podcasters level up. Until the big advertisers and audiences show up, Bennett and Headstuff will be waiting: “If we just continue to make really good shows and make the space a place where people really want to be, then we can’t go wrong.”