Editor’s note: Gannett and GateHouse officially announced the merger Monday afternoon. Here’s the company announcement, confirming that the company will be called Gannett, be based at Gannett’s headquarters, and retain GateHouse’s New Media Investment Group CEO Mike Reed.

Barring last-minute complications, the merger of America’s two largest newspaper chains, GateHouse Media and Gannett, could be announced as early as Monday morning, multiple confidential industry sources close to the transaction have told me. The parties aim to make that announcement before the stock market opens, which would put it about 24 hours before both companies are scheduled to report their less-than-stellar Q2 2019 earnings.

As bankers finalize valuations and as both boards meet by phone this weekend, the timing could be pushed back another day or so — and though it seems unlikely, there’s always a chance if could be further delayed. But those involved believe it’ll be a done deal by morning.

As I reported here two weeks ago, the two chains have both grown more comfortable with a combination that will produce an unprecedented giant in American daily journalism. The combination — which parties say will take the Gannett name and its headquarters outside D.C. in McLean, Virginia — produces a company that will likely own and operate 265 dailies and thousands of weeklies across the country. That’s more than one-sixth of all remaining daily newspapers. It will claim a print circulation of 8.7 million — dwarfing what would become the new No. 2 company, McClatchy, and its 1.7 million. Its digital audience will claim a similarly outsized lead, helpful for selling national advertising.(Of course, scale is relative. The merged company would control an unprecedentedly large share of American newspapers. But those newspapers, even when bought in bulk, are far weaker than they were in the industry’s glory days, with shrunken revenues, circulation, and influence. And no matter how big its combined digital audience, the new company’s share of attention will still be no match for Google, Facebook, and the lesser nobility of digital advertising. It’s a very big slice of a much smaller pie.)

As the company that has achieved the long-sought rollup of the daily press, the new Gannett will exert a profound impact on the news industry itself, hundreds of communities, millions of readers and on the very future of the craft of journalism.

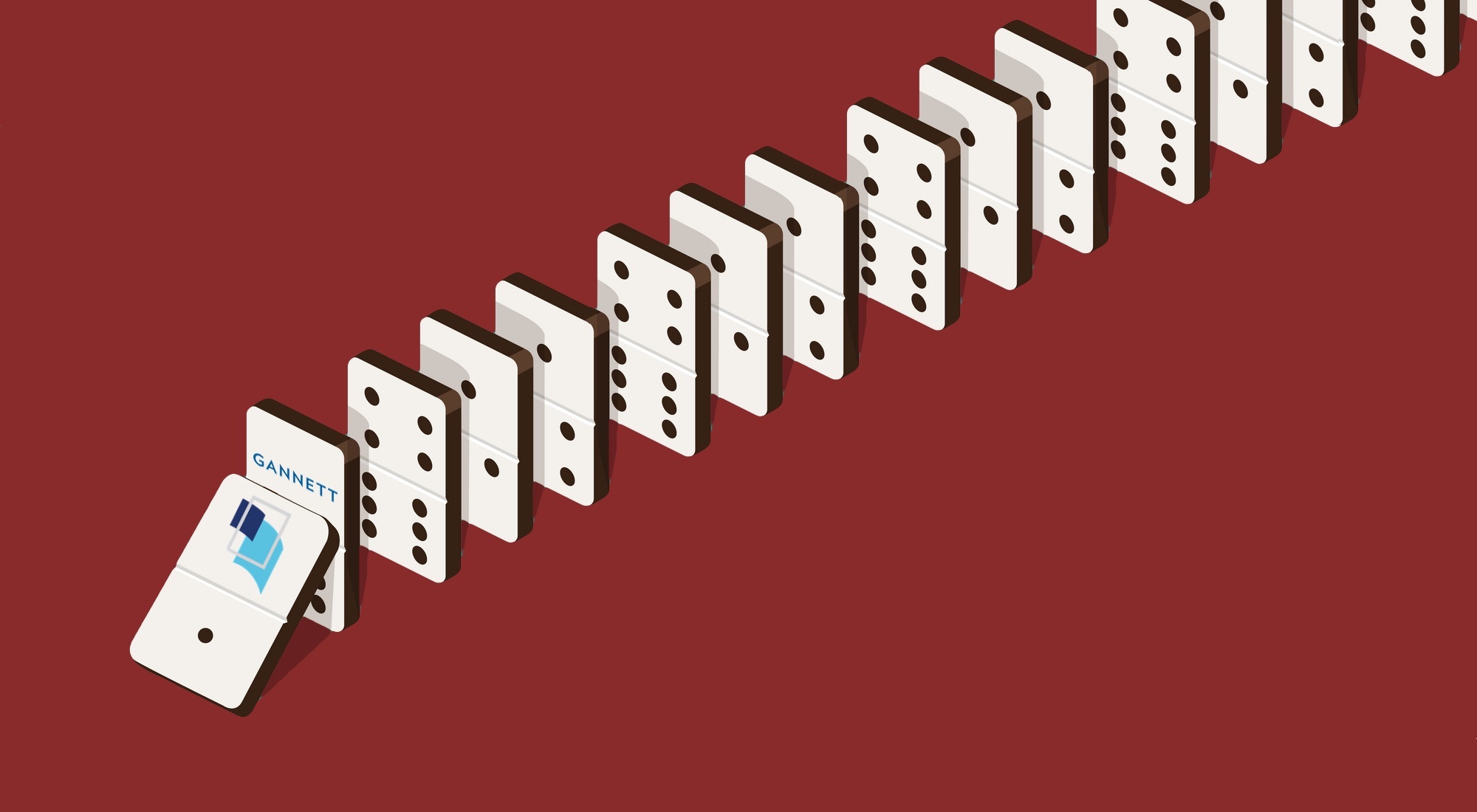

This merger produces a new cascade of questions. The first: What are the next dominoes this transaction sets up in the consolidation of the newspaper industry this transaction? Eyes are focused squarely on McClatchy and Tribune, though both Lee Enterprises and MNG Enterprises — the latest name for the collection of papers owned by Alden Global Capital — are also drawing attention. Back in January, I dubbed the industry-wide urge to merge the 2019 Consolidation Games, and this deal certainly sits atop the medal podium just past mid-year.The deal itself still looks to be along the lines I outlined two weeks ago — designed to generate $200 to 300 million in annual cost savings in an effort to give them more time to “figure out their digital transition,” as they like to say.

GateHouse, through its New Media Investment Group (NEWM) holding company, is the acquirer. That’s surprised many observers, given Gannett’s greater circulation, cash flow, revenue, and market cap. But New Media — led by the industry’s grand acquisitor, CEO Mike Reed, and having the deal energy and resources to bring the financing together — is squarely in the driver’s seat.

Gannett’s shareholders (with 114 million shares outstanding) will receive $6 or more per share in cash, plus shares in the new company, adding up to a price in the $12 range. That’s a little more than a dollar over Gannett’s Friday closing price of $10.75, but it’s four dollars a share more than the $7.90 Gannett was at before investors learned the deal was likely and speculated the price up.

(My efforts to reach both companies for official comment this weekend were unsuccessful.)

But there is one new big player in this story: Apollo Global Management, the private equity firm which will lead the financing of the merger, sources tell me. Apollo’s name had been heard around the industry for a while, most prominently four years ago when it came close to buying what was then branded as Digital First Media from Alden. That deal fell apart at the last minute over price. (If you’ve seen Apollo in the news lately, it was likely in the context of its founder distancing himself from the sexual predator Jeffrey Epstein after a financial relationship spanning more than a decade.)

In this deal, Apollo is supplying much of the money to get the deal done, with financing that sources tell me could approach $2 billion and a major debt service to match in 2020 and beyond — limiting how much any cost savings can be invested into newspapers’ future. Financing in the merger must both pay off Gannett shareholders partly in cash and essentially refinance both companies’ debt. That debt, after cash on hand is subtracted, amounts to about another $1 billion. In its would-be DFM deal in 2015, Apollo saw itself as a strategic consolidator with a game plan throw the switch from print to digital more rapidly. (It’s worth re-reading my story Thursday on newspaper companies’ increasing plans to stop printing their products seven days a week.) Mike Reed will be at the reins of the new company as New Media acquires Gannett. (“Acquisition” and “merger” are roughly synonymous terms in this transaction.) This deal represents his ascension to the top of the trade, reinforcing what he told Nieman Lab readers last year in lengthy interview: The rollup of the newspaper industry is inevitable. Reed built the GateHouse behemoth out of bankruptcy with strong financial backing, including lower-cost access to capital from the Fortress Investment Group. For its efforts, Fortress has already been rewarded well, taking in $21.8 million in management fees and incentive payments alone in 2018. Dealmakers in this merger face the financial reckoning of buying out Fortress’ contract; that’s been one of the last sticking points in final valuation talks, say sources.So what will this new company, a supersized Gannett, look like? Don’t expect an unveiling of the daily operating head of the company (presumably someone reporting to Reed) when the deal is announced. Instead, sources tell me they’ll point to further announcements down the road as it moves through the regulatory approval process.

The agreement does indeed require federal approval, with a HSR (Hart–Scott–Rodino) review for antitrust purposes ahead. Department of Justice antitrust review is unlikely to prevent the completion of the deal, but it could take it through some unanticipated turns. Tronc/Tribune found itself stymied by DOJ’s antitrust division in two deals — one for the Orange County Register, the other for the Chicago Sun-Times — a couple of years ago. Those two cases focused on claimed monopolistic limitation in regard to advertisers and/or subscribers in a single market. (In these cases, from uniting the L.A. Times with the Register or the Chicago Tribune with the Sun-Times.)

But GateHouse and Gannett’s holdings, as numerous as they are, may not be considered as competing head-to-head in any single market. The big question is how DOJ will look at the substantial regional clustering of properties this deal would bring. In south Florida and in Ohio, for instance, the regional clustering of Gannett/GateHouse papers would be profound. But it’s that sort of clustering there in many places across the country that drives the cost-saving synergies that form the entire financial purpose of the deal.

(In Florida, a combined company would own dailies in Jacksonville, West Palm Beach, Sarasota, St. Augustine, Naples, Brevard County, Fort Myers, Pensacola, Tallahassee, Gainesville, Lakeland, Daytona Beach, Ocala, Winter Haven, Panama City, the Treasure Coast, the Space Coast, and more. In Ohio, it would own Columbus, Cincinnati, Akron, Canton, and more — three of the state’s four largest papers by weekday circulation.)

Will DOJ take a stand on such regional clustering? Will it find that print advertisers could be priced unfairly? Will it make an argument that the continuing spikes in the price of a print subscription is unfair to those print readers who remain? One fundamental determination: Do weakened newspapers, even if merged, really still have the ability to dominate a market to an extent that would be unfair?

Also: Since this is the first deal to create a truly national newspaper company footprint, might DOJ consider national market domination along the same lines?

Neither GateHouse nor Gannett expect such review to be a major stumbling block. Failing that kind of unexpected outcome, expect the new company to be ready to set up shop by January.

If DOJ expresses concern within its first 30-day review period, the new Gannett could agree to sell off a few titles in contested locations. It’s also quite possible that Reed has already anticipated such sales, both to satisfy DOJ and/or to reduce the debt necessary to get this deal done. Other newspaper chains would likely be interested in buying individual properties that could help them cluster.

Will this announcement push others back to the merger table?

Close observers of the industry now expect the Tribune board to feel more pressure to make a deal. Tribune, along with its past pursuer McClatchy, is one of several companies set to report earnings this week. With the GateHouse/Gannett deal, Tribune loses a potential dance partner. Tribune/Tronc had a long and often bitter battle to tie up with Gannett (a deal semi-negotiated last summer). That presumably leaves it turning its eyes back to Sacramento, where McClatchy will likely be prepared to pitch another iteration of a deal.

McClatchy may well be able to shave a dollar or two off of its rejected December offer and get a deal done. The continuing stumbling block, sources say: Michael Ferro, whose group still controls a quarter of Tribune and who nixed the December deal. Both companies’ need consolidation for the same reasons Gannett and GateHouse do: cost savings to buy time.(Observers noted McClatchy’s recent filing of a “waiver” request with the IRS to put off payments into its underfunded pension fund and wondered whether it is a sign of financial weakness. That filing indeed indicates tight liquidity, though that barely counts as news for McClatchy, which has been managing down/deferring its still-substantial debt pile of $816 million. While these tight finances do point to the short-term value of merger, they don’t likely indicate an imminent issue. History will note that McClatchy, unlike GateHouse and Tribune, never declared bankruptcy in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Neither did Gannett.)

Then there’s Alden. As I wrote earlier in the year, it probably stands to make some money off its supposed hostile takeover attempt of Gannett in January, depending on how much Gannett stock it retains. Alden president Heath Freeman, vilified as he is in the press, appears to have worked a successful strategy. Did he ever really intend to buy Gannett, as clumsy as his effort ended up being? Or did he just want to put it in play — as he clearly succeeded in doing — to make some money on the Gannett share holdings he had?

So what does Alden do now with its MNG papers — especially in California, where it owns more than 20 papers, including in San Jose, Oakland, Orange County, Long Beach, and Riverside? Will it find a new partner, or some other way to exit the struggling business? And then there’s Lee Enterprises, itself dealing with debt-refinancing issues and maybe another company to add to the would-be consolidation mix.

For the journalists inside what will become the new Gannett, and for their readers, the immediate future is hard to chart. Financial realities drive this deal — and that means cutting. We’ll hear the two companies talk about synergies in that $200 to 300 million range. How do those numbers work?

At the low end, “figure $200 million minus $100 million the first year,” explains one savvy financial insider. “It will cost them about $100 million in severance-plus to get the savings they want. Then there’s a savings of $200 million net a year.”

But wait: That might sound good if newspaper revenues were stable. They’re not, expected to drop another 5-plus percent in 2020 and likely continued decline after that. That could add up to another $100 million vanished from top-line revenues in 2020.

Where will the synergistic efficiencies come from? In order, consider these the sources:

Let’s remember: These synergies are the point of the deal. But the financing required to put the deal together means paying off a lot of debt — up to that $2 billion number. That could cost the new company something in the neighborhood of $150 million or more in annual debt service, given the high rate of interest Apollo has likely extracted in its term sheet. That annual payment will significantly constrain the new company’s ability to invest in its future — remember, that “digital transition” they keep talking about.

As this deal get finalized and then dissected — by the market and by those who care about local journalism — we’re left with this point from one in-the-fray source to ponder: “If executed well, this company will be much more likely to lead to the further rollup of the industry.” The further rollup.

The merger of GateHouse and Gannett is not the checkered flag at the end of the race. It’s more of a starting gun.