Threatening to leave Facebook, or talking about how you should spend less time on it, is common. Actually leaving is less common (though it is happening). If you do leave, it might be good for you…and you also might miss it: A study of 1,769 U.S. undergrads found that those who got off Facebook for a week consumed less news, experienced greater wellbeing…and, uh, valued Facebook 20 percent more highly, in monetary terms, than they had before they took their break.

The paper is “The economic effects of Facebook,” published this week online in the journal Experimental Economics by Roberto Mosquera of Ecuador’s Universidad de las Americas and Mofioluwasademi Odunowo, Trent McNamara, Xiongfei Guo, and Ragan Petrie of Texas A&M University. In spring 2017, they surveyed A&M undergrads on how what they think a week of Facebook use is worth. They then randomly assigned them into two groups — one that went off Facebook for a week and one whose Facebook use wasn’t restricted. After that, they asked them to place a monetary value on Facebook again.

Their results:

Overall, the effects our study finds on news awareness, news consumption, feelings of depression, and daily activities show that Facebook has significant effects on important aspects of life not directly related to building and supporting social networks.

Participants came into the study spending a mean of 1.9 hours per day on Facebook. (Yes, this is a lot. Emarketer estimates that U.S. adults will spend an average of 38 minutes a day on Facebook this year. It’s also probably music to Facebook’s ears, given that young people stepping away from the app has been a major point of concern in recent years.) About 15 to 30 minutes of that time was spent consuming news.

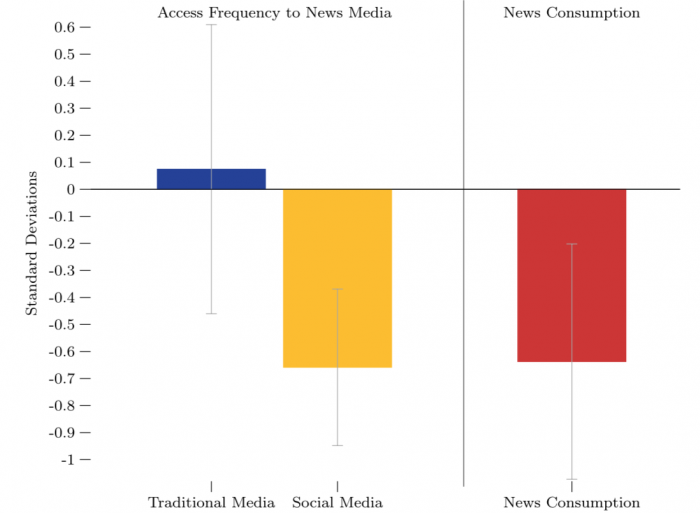

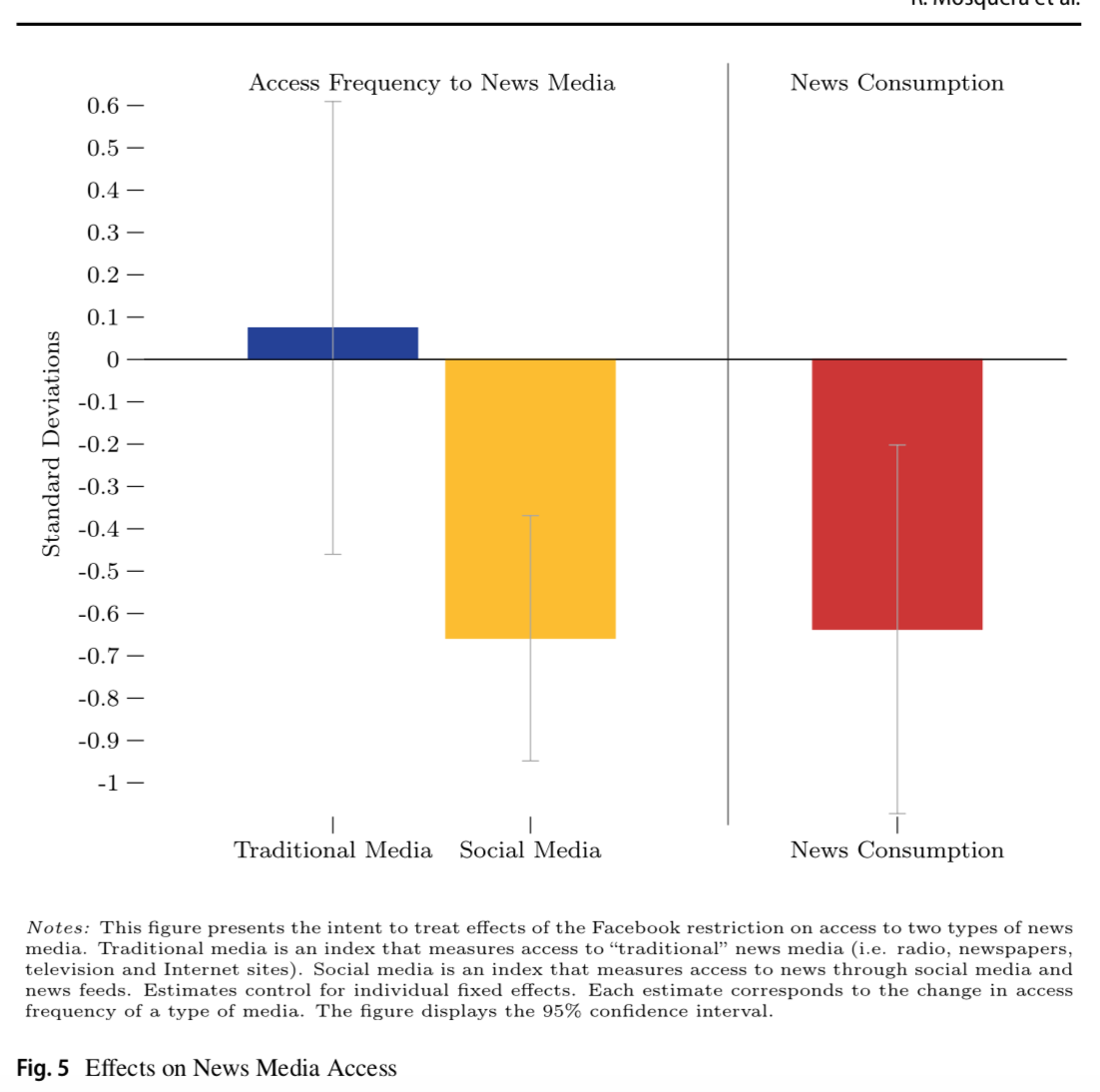

When half the participants took a Facebook break, the researchers found that they didn’t substitute traditional media for the news they’d been getting on Facebook: “On average, participants in the Facebook restriction group significantly decrease their consumption of news by 0.64 standard deviations with respect to the baseline (p value < 0.05), and this effect is consistent across all news types" — weather, sports, politics, and so on. This is some evidence that when people stop getting news from Facebook, they don’t necessarily start getting it somewhere else; traditional news consumption didn’t fill the void created by limiting Facebook news consumption.

And…they wanted back on. After the week off, the researchers found, participants assigned Facebook a higher monetary value. The researchers have some theories about why:

The reduction in access to news may simply not be compensated by a better mood and healthier activities. [Ed. note: LOL!] Individuals would then need a higher payment to be willing to be off of Facebook for another week. Second, the increase in value is consistent with withdrawal effects of an addictive good. If being on Facebook creates addiction, then the week-long restriction should increase the desire to be back on Facebook. This would also explain the rise in value of Facebook. Third, Facebook further affects other dimensions of daily life that were not captured in our study. For instance, we do not measure the effects of losing access to Facebook’s messenger service.

The findings of this study are consistent with NYU research that came out earlier this year. That study also found that users who get off Facebook report improvements in well-being and consume less news.

(This is Josh subbing in for Laura for a minute.)

There is one other interesting finding in the paper that raises a few questions. Researchers also measured participants’ news awareness in the following way:

In the week prior to the survey, we collected headlines from the front page of the eleven most popular newspapers as ranked by the Pew Research Center, including The New York Times, Washington Post, USA Today, Wall Street Journal, LA Times, New York Daily News, New York Post, Boston Globe, San Francisco Chronicle, The Chicago Tribune and The British Daily Mail. We used Breitbart as the source of skewed news. There were no extraordinary news events during this period, like a mass shooting or major natural disaster, that might bias news knowledge. The participant is shown six headlines randomly chosen from the pool of mainstream sources and one randomly chosen from the skewed source and asked to identify if the event occurred or not. From the six mainstream sources, two headlines are changed slightly so as to make the headline false. All other headlines did appear on the front page of a newspaper or on Breitbart.

As for why they chose Breitbart, “its internet traffic as of March 2017 surpassed other major skewed news sources and was similar in magnitude to that of mainstream news sources such as The Washington Post according to alexa.com.”

A few quibbles up front: For the record, it’s a bit of a stretch to put Breitbart and The Washington Post in the same weight class in terms of traffic. According to Comscore data, Breitbart’s best traffic month ever, January 2017, hit 17.3 million uniques; The Washington Post in March 2017 had 86.5 million. Researchers also included The Daily Mail as a mainstream news source, which is at least debatable. One final note: It’s not quite accurate to call what was shown to the students “headlines”; some were headlines, but others were lengthier story ledes.

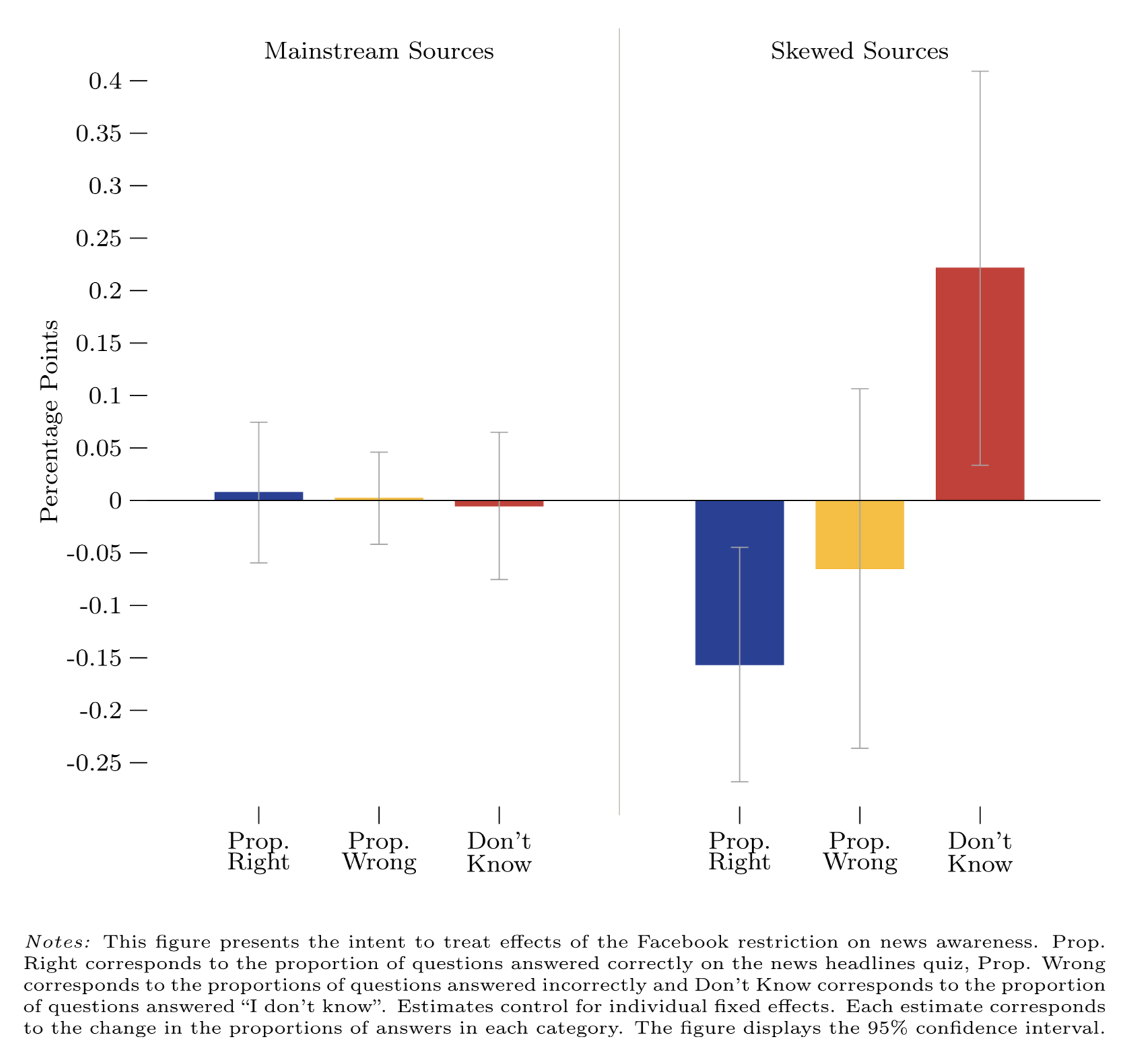

The group that was restricted from Facebook was asked, after their week off, to take the news quiz again. They found “no significant effect of the restriction on news awareness for headlines from mainstream sources”; that is, when the participants who’d been off Facebook were asked to judge whether mainstream news headlines had actually occurred, the Facebook break didn’t make them more or less likely to be right. In the case of the Breitbart stories, however, “those who experienced a week off of Facebook [were] 22.1 percentage points more likely to be uncertain about whether or not a politically-skewed news headline [was real].”

In other words, those who’d been off Facebook for a week were just as good at identifying real or fake mainstream media stories as they’d been before. But the time away had left them significantly less sure what to make of the Breitbart story — fewer people thought its headline was both real and unreal, and more people said they didn’t know.

That said — take caution before taking this particular result too seriously. The pre/post effect on a “politically-skewed news headline” is derived entirely from two randomly selected Breitbart headlines, one before the week and one after. You can see the questions here (p. 6). That puts a lot of weight on the particular headlines the researchers picked — and it’s worth questioning their choices.

In the pre-test news quiz, the Breitbart headline selected was “MSNBC analyst calls for ISIS to bomb Trump property.” Subjects were asked to answer, about that and six other stories: “Did these events happen in the previous week?”

We’re already running into problems here, because that is a real Breitbart headline. But it’s also a B.S. headline; the MSNBC analyst did not “call for ISIS to bomb Trump property,” as Snopes and, really, any non-politically motivated observer could determine. (The analyst in question, Malcolm Nance, is a retired Navy intelligence officer who worked in counter-terrorism for 35 years and who had written the book Defeating ISIS the year before. Nance said on TV that he had received 31 death threats as a result of the Breitbart story.)

So “did this event happen in the previous week”? Yes, in that the story was published; no, in that it’s insane.

How about the post-test Breitbart headline? It’s the significantly less inflammatory “Donald Trump wants to send astronauts to Mars during his presidency.” Which is…just a news story, reporting something Trump said at a NASA photo-op and which was reported plenty of other places.

Using just those two headlines — only poorly comparable in a host of different ways — to support such a finding is questionable, at best.