We know that many news consumers have trouble trusting their news sources and that newsrooms still have a long way to go in (re)building that trust.

For some news organizations, that’s meant testing out ways to let readers see more context around the story — whether that’s showing how the story was produced, how it fits into a larger narrative, or the editorial values that back the journalism. Research by the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas has found that only 6.7 percent of people surveyed said news sources do enough to explain how and why they decide what stories to cover.

Today, that same center released its findings from an attempt to be more transparent, done in coordination with three McClatchy newspapers. If you add contextual information to a story explaining how and why it was reported, will it lead readers to trust it more?

(Spoiler alert: not so much. People have to notice something before it can change their minds.)

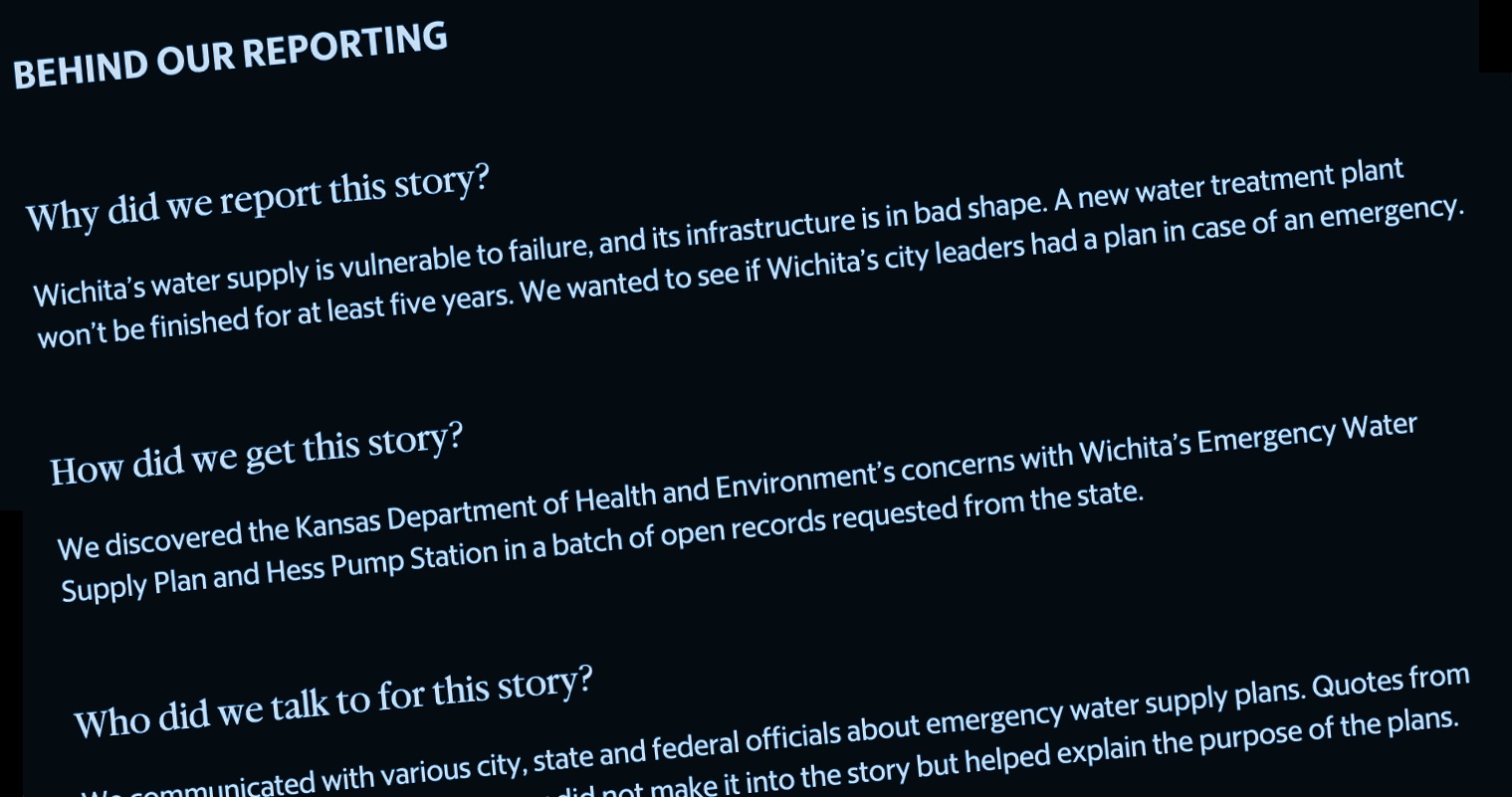

At three newspapers — The Wichita Eagle, El Nuevo Herald, and The Sacramento Bee — reporters added a box featuring those explanations to one of their stories. You can see a live example of one here; it’s a light grey card that asks and answers “Why did we report this story?” Readers can then expand it to see more explanation.

But after surveying 321 readers of those stories, it turns out that most readers didn’t notice the box at all — and it didn’t impact their trust of the story in any significant way. Banner blindness isn’t just for ads, it seems.

Researchers tested the placement of the box: in the middle of the story, at the bottom, or not present at all. Of those surveyed, only 33.7 percent said they remembered the “Behind Our Reporting” box when it was embedded in the story text, while 21.2 percent remembered it when it was at the bottom of the page. (The difference isn’t statistically significant, though.)

“This study and other user research we’ve conducted at McClatchy shows that readers skim over elements outside the story body, especially non-text-based elements that can be confused with advertising,” Abby Reimer, senior manager of UX and strategic projects for McClatchy, said. “We are in the process of streamlining our story pages, including moving to a rail-free design, so readers can identify and pursue the highest-value action on our story pages.”

And when it comes to trust?

When participants were asked to rate the trustworthiness of the article, the news organization or the reporter, whether people saw an article with a BtS [“Behind the Story”] card or not didn’t significantly change their ratings. It also did not matter whether the BtS card was placed inline or at the bottom of the page. The lack of differences is possibly due to the fact that few people reported noticing the card, even in articles where it was present.

When readers were shown a Behind the Story card on its own — not in the context of a story — “most readers said that the card would increase their trust in a news organization.” But put one in an actual story and not enough people notice it to make a difference.

That’s worth remembering, given that news stories online are often skimmed more than read: Visual cues meant to influence readers’ perceptions have to be, you know, seen to have an effect.

Caroline Murray, one of the researchers on the study, said the appeal of an addition like this one is its accessibility to any newsroom.

“Maybe if you’re a small organization you can’t do something like The New York Times with blockchain, but you definitely can with a Behind the Story card,” Murray said. “Journalists already have all that access to the information. It’s really about adding it to the story page in a way that’s compelling.”

Now McClatchy and other news organizations can experiment with page design to figure out what placement best works for their readers, Murray added.

The Center for Media Engagement conducted a similar experiment with Gannett newspapers USA Today and The Tennessean last year using “Explain Your Process” boxes and also tested a “demonstrating balance” theory, which was inconclusive.

You can read the full study here.