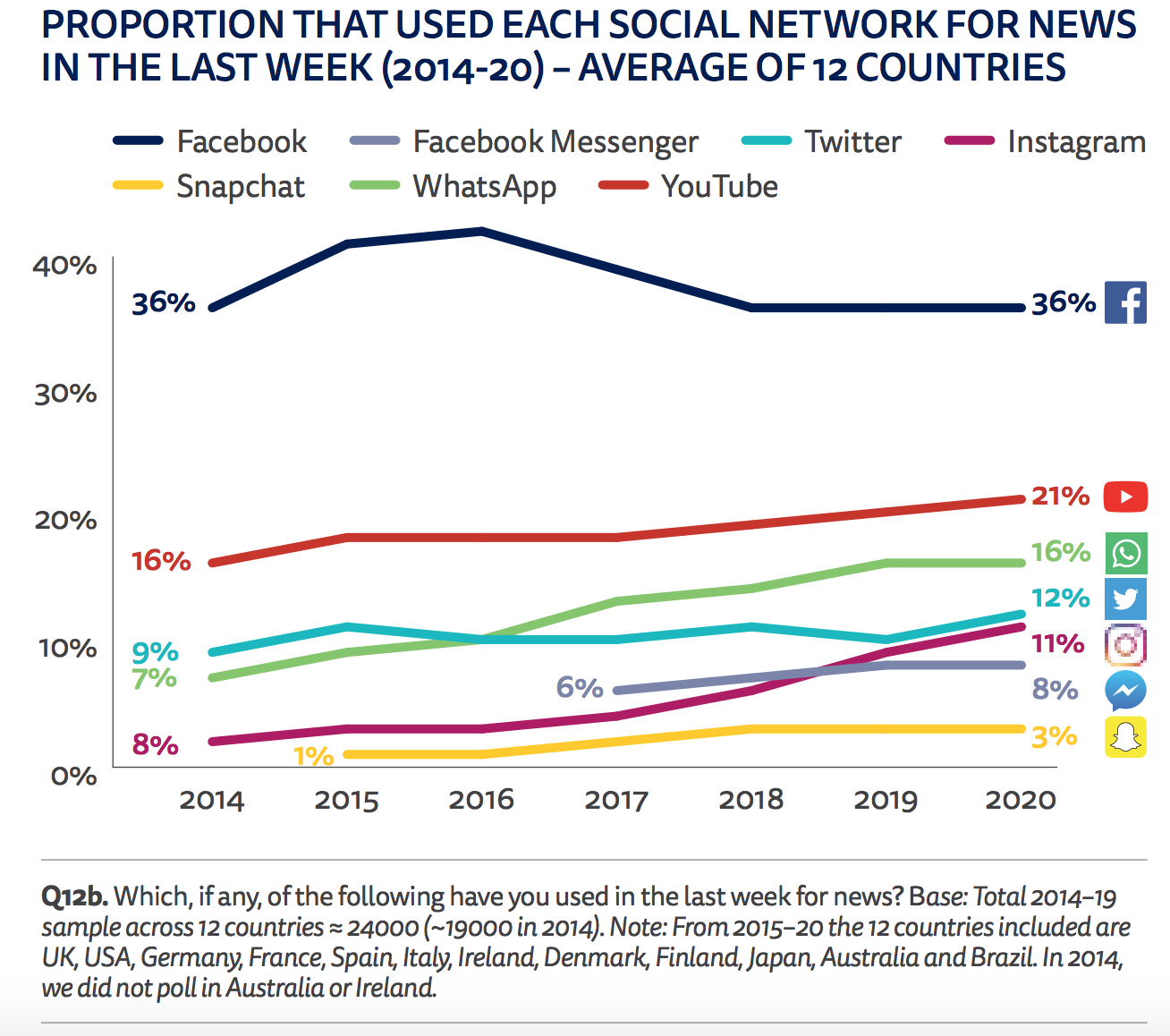

The percentage of people paying for news online continues to increase — and people may even pay for more than one subscription. People worldwide blame domestic politicians most for spreading false and misleading information online. And more people than ever are getting news from Instagram, with 18- to 24-year-olds more than twice as likely as other age groups to prefer getting their news from social media.

These are some of the findings from a big new report out Tuesday evening from Oxford’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. The Reuters Institute’s Digital News Report for 2020 surveyed more than 80,000 people in 40 countries about their digital news consumption. (Included in the report for the first time this year: Kenya and the Philippines.)

The research is based on YouGov surveys conducted earlier this year, as well as additional surveys about paying for news in the U.S., UK, and Norway and about the impact of COVID-19 on media consumption in six countries (the UK, USA, Germany, Spain, Argentina, and South Korea).

Here are some of the most interesting findings from the report:

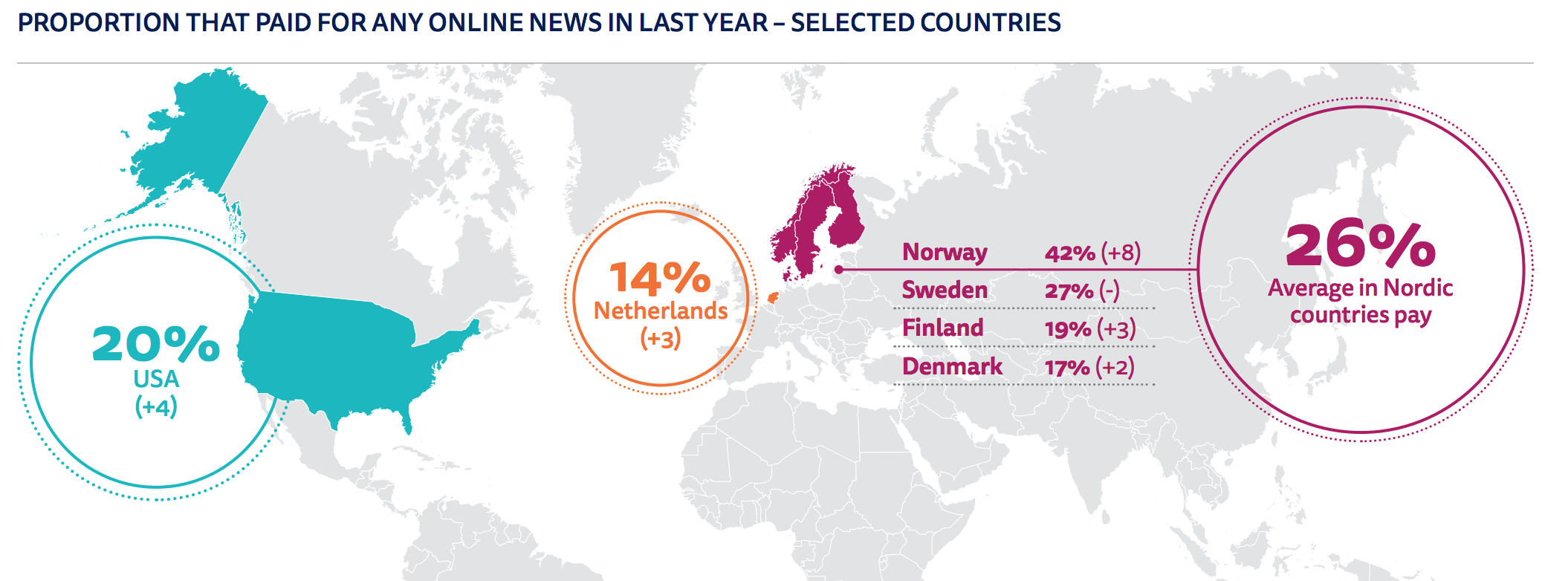

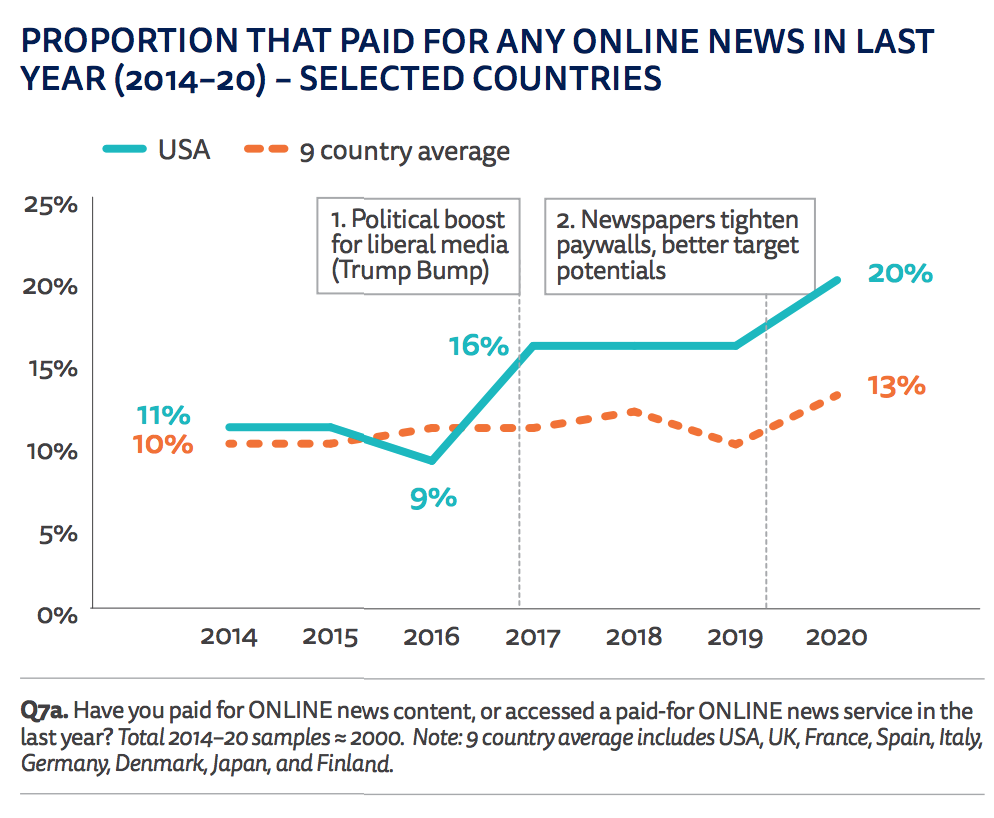

In last year’s report, Reuters noted that more publishers worldwide were adding paywalls. And this year, it’s clear that in many countries, more people are paying. The percentage of people in the U.S. who pay for news is 20 percent (up from 16 percent last year); in Norway it’s 42 percent (up from 34 percent last year). “We’ve also seen increases in Portugal, the Netherlands, and Argentina, with the average payment level also up in nine countries that we have been tracking since 2013,” the authors note.

The biggest winners tend to be large national news brands, though Norway is different:

Around half of those that subscribe to any online or combined package in the United States use The New York Times or The Washington Post and a similar proportion subscribe to either The Times or the Telegraph in the UK, though in much smaller numbers. In Norway the quality newspaper Aftenposten leads the field (24% of those that pay), along with two tabloid newspapers that operate premium paywall models, VG (24%) and Dagbladet (14%). One surprise in these data is the extent to which people subscribe to local and regional newspapers online in Norway (64%). Most local publishers in Norway charge for online news, with a total of 129 different local titles mentioned by our respondents. In the United States 30% subscribe to one or more local titles, with 131 different titles mentioned. By contrast in the UK only a handful of local publishers have put up a paywall.

Paying for more than one subscription has also become increasingly common in the U.S. and Norway, but is still rare in the U.K.:

In all three countries the majority of those who pay only subscribe to one title, but in Norway more than a third (38%) have signed up for two or more — often a national title and a local newspaper. It is a similar story in the United States with 37% taking out two or more subscriptions, with additional payment often for a magazine or specialist publication such as The New Yorker, The Atlantic or The Athletic (sport). By contrast, in the UK a second or third subscription is rare, with three-quarters (74%) paying for just one title.

Donations for news are also increasing; The Guardian continues to be incredibly successful in this arena:

In the United States 4% now say they donate money to a news organization, 3% in Norway, and 1% in the UK. The Guardian has one of the most successful donation models of any major brand, with over a million people having contributed in the last year. According to our data, almost half of all the relatively small number of donations in the UK (42%) go to the Guardian, but most are one-off, with an average payment of less than £15.

88% of people in the U.S. who pay for news think they’re still likely to be paying a year from now, and across the U.S., U.K., and Norway, “around half of those who currently have free access say that they might start paying if their free access runs out,” the authors note. “This is encouraging, and perhaps more encouraging still is that these figures imply retention rates that are comparable to those for subscriptions to video and audio streaming services like Netflix and Spotify.”

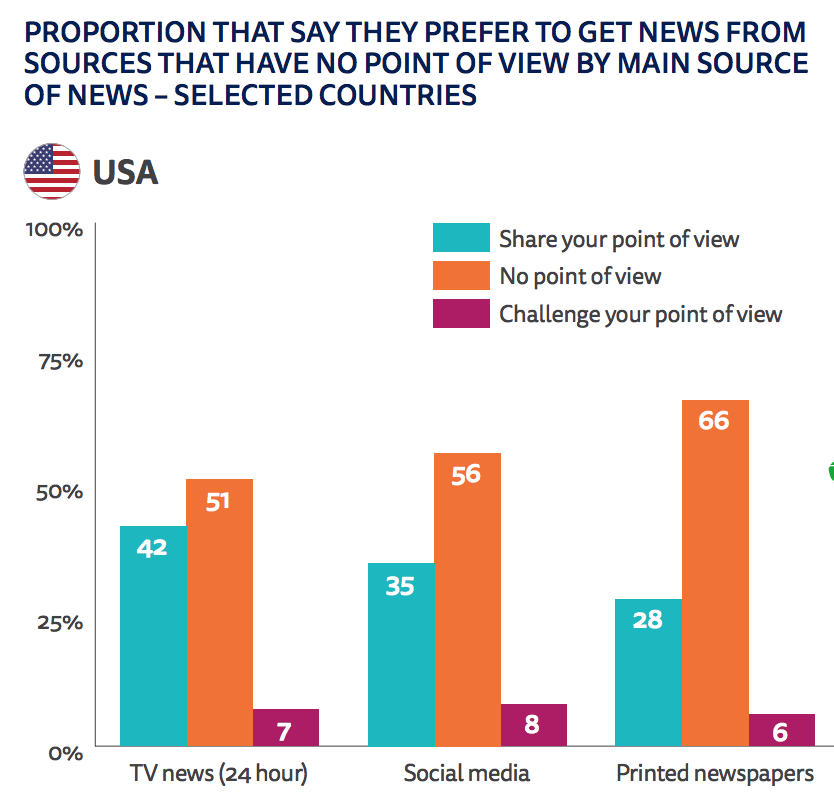

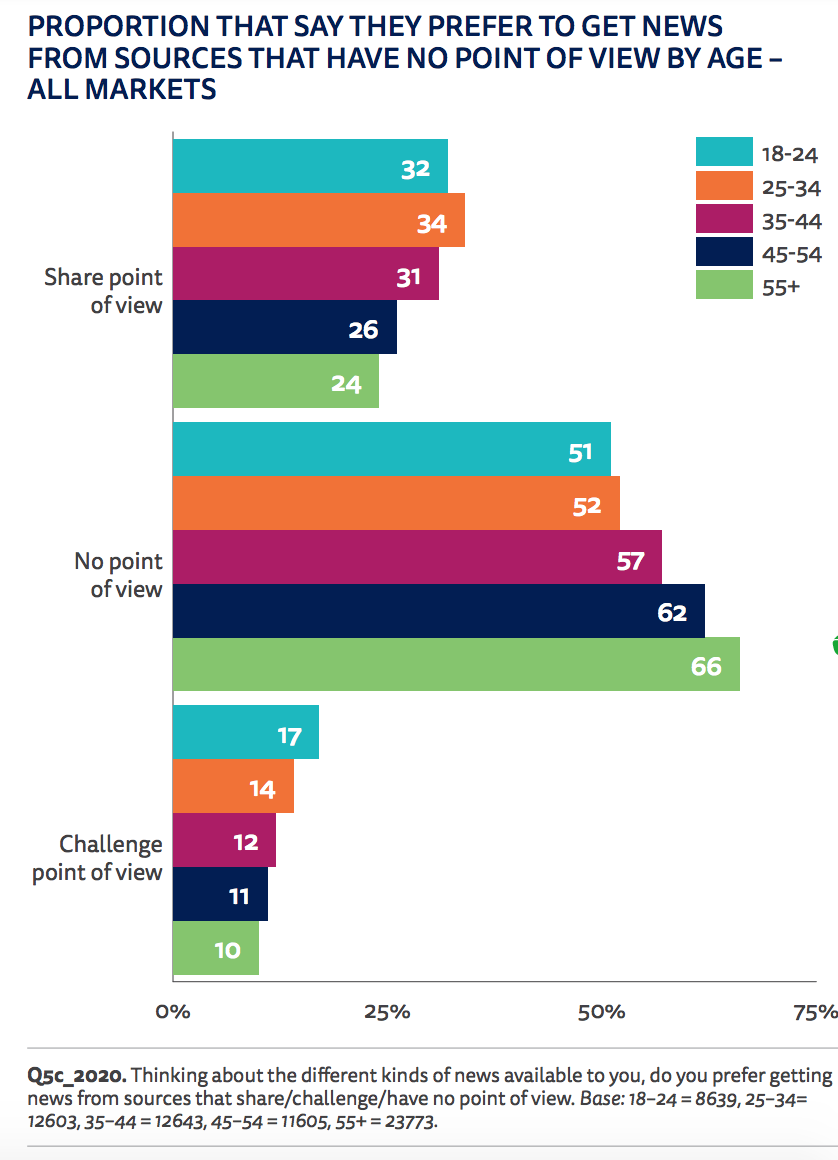

People in many countries say that they prefer to get their news from sources that “have no point of view.” In the U.S., people who get most of their news from cable TV are also most likely to prefer news sources that “share their point of view.”

Of course, the premise that it’s actually possible or desirable for any news source to have “no point of view” is increasingly under debate — and Reuters finds that “across countries, young people are less likely to favor” this type of news. “They still turn to trusted mainstream brands at times of crisis but they also want authentic and powerful stories, and are less likely to be convinced by ‘he said, she said’ debates that involve false equivalence,” the authors note.

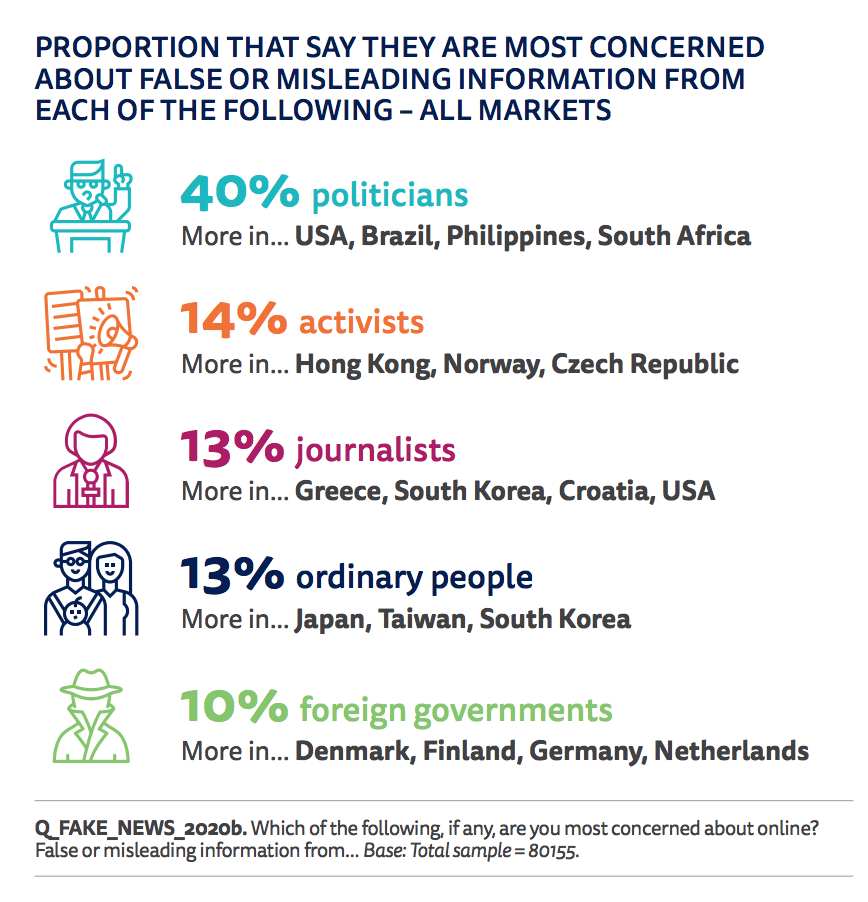

Across 40 countries, 56 percent of respondents said they’re “concerned about what is real and fake on the internet when it comes to news.” (67% of those in the U.S. say so, behind only Brazil, Portugal, Kenya, and South Africa.) Across countries, people see domestic politicians as most responsible.

But:

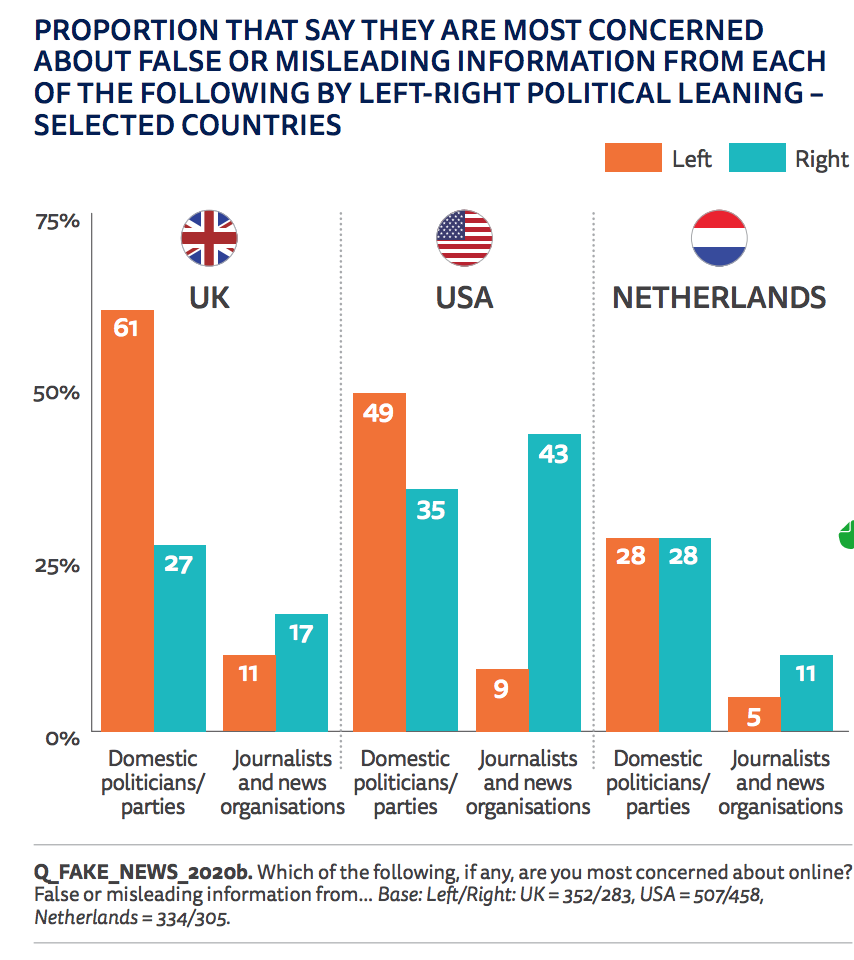

Political starting positions can make a big difference when it comes to assigning responsibility for misinformation. In the most polarized countries, this effectively means picking your side. Left-leaning opponents of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson are far more likely to blame these politicians for spreading lies and half-truths online, while their right-leaning supporters are more likely to blame journalists. In the United States more than four in ten (43%) of those on the right blame journalists for misinformation — echoing the president’s antimedia rhetoric — compared with just 35% of this group saying they are most concerned about the behavior of politicians. For people on the left the situation is reversed, with half (49%) blaming politicians and just 9% blaming journalists.

You can read the full report here.