The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

How much does exposure to fake coronavirus information change people’s behavior? What about when it comes from the president? In a working paper (not yet peer-reviewed) by Ciara M. Greene and Gillian Murphy of Ireland’s University College Dublin and University College Cork find that, in some cases, exposure to false information about the pandemic can change people’s actions — but the size of the effect is small, at least in Ireland. From the paper:

In this study, we exposed participants to fake news stories suggesting, for example, that certain foods might help protect against Covid-19, or that a forthcoming vaccine might not be safe. We observed only very small effects on intentions to engage in the behaviors targeted by the stories, suggesting that the behavioral effects of one-off fake news exposure might be weaker than previously believed. We also examined whether providing a warning about fake news might reduce susceptibility, but found no effects. This suggests that, if fake news does affect real-world health behavior, generic warnings such as those used by governments and social media companies are unlikely to be ineffective.

Greene and Murphy recruited the 3,746 participants for their study via a call-out in TheJournal.ie. They note that “the majority of participants were well-educated, with 2,395 participants (64%) having earned at least an undergraduate degree.”

Participants were shown public health and misinformation warning posters “designed to mimic the format and style of government-issued public health messages relating to Covid-19 in the Republic of Ireland”; they were also shown four fake stories and four real stories. During the study, they weren’t told that some of the stories were fake. (They were debriefed afterward.)

These were the fake stories:

1. “New research from Harvard University shows that the chemical in chili peppers that causes the ‘hot’ sensation in your mouth reduces the replication rate of coronaviruses. The researchers are currently investigating whether adding more spicy foods to your diet could help combat Covid-19”2. “A whistleblower report from a leading pharmaceutical company was leaked to the Guardian newspaper in April. The report stated that the coronavirus vaccine being developed by the company causes a high rate of complications, but that these concerns were being disregarded in favor of releasing the vaccine quickly.”

3. “A study conducted in University College London found that those who drank more than three cups of coffee per day were less likely to suffer from severe Coronavirus symptoms. Researchers said they were conducting follow-up studies to better understand the links between caffeine and the immune system.”

4. “The programming team who designed the HSE1 app to support coronavirus contact-tracing were found to have previously worked with Cambridge Analytica, raising concerns about citizen’s data privacy. The app is designed to monitor people’s movements in order to support the government’s contact-tracing initiative.”

These were the real stories:

1. “A new study from Trinity College Dublin revealed that vitamin D is likely to reduce serious coronavirus complications. The researchers urged the government to advise Irish citizens to take daily vitamin D supplements.”2. “Mixed-martial arts fighter Conor McGregor posted an online video urging the Irish government to enforce a complete lockdown, with the help of the army. ‘I urge our government to utilize our defense forces,’ he stated.”

3. “Sinn Féin President Mary Lou McDonald called off two Sinn Féin rallies in March, after a case of coronavirus was reported at her children’s school.”

4. “As most of Europe is in lockdown, Sweden is pursuing a different strategy against COVID-19. Pubs, restaurants, gyms and most schools remain open in the Scandinavian state, with the government relying on personal responsibility for compliance rather than strict enforcement. Official guidance states that citizens may socialize, as long as they stay at ‘arm’s length’ from each other.”

The study also had a false memory component: Participants were asked if they remembered seeing six news stories — all four true stories and two randomly selected fake ones.

The researchers found that “exposure to misinformation was associated with small but significant changes to two of the four critical health behaviors assessed”:

Participants who viewed a story about privacy concerns relating to a contact-tracing app reported being less willing to download the app, while participants who remembered having seen this story before also reported small decreases in intention. Participants who reported a false memory for the coffee story reported stronger intentions to drink more coffee in future, though notably the opposite effect was observed among participants who were merely exposed to the story. No significant effects of seeing or remembering stories about the benefits of eating spicy food or problems with a Covid-19 vaccine were observed; effects were generally in the expected direction, but did not reach statistical significance. Truthfulness ratings were correlated with behavioral intentions; participants who believed stories promoting a particular behavior (e.g. drinking coffee or eating spicy food) tended to report stronger intentions to engage in that behavior. Similarly, participants who believed stories encouraging caution about particular behaviors (e.g. downloading a contact-tracing app or getting a vaccine) were less likely to engage in that behavior in future.

“We report some evidence that exposure to fake news may ‘nudge’ behavior, however the observed effects were very small,” the researchers note. However, they raise the question of what happens when people are exposed to a fake story multiple times, over time:

It is important to note that effects in the present study are based on a single exposure to a novel fake news story. Real-world behavioral effects may arise following multiple exposures to a story; multiple sources might increase consumers’ faith in a story and thus influence their subsequent behavior. Indeed, just two exposures to a fake news story can increase its perceived truthfulness (Pennycook et al., 2018).

The study took place in Ireland, so its applicability to the United States is less clear. “Coronavirus issues are relatively politically neutral in Ireland, where the data were collected, in comparison with the U.S. where the virus has become something of a political football,” Greene told me in an email, adding:

In some of our other fake news research, using similar methods, we’ve found that acceptance of misinformation tends to be higher when the fabricated stories align with the participant’s existing views. For example, we have a paper under review at the moment examining fake news related to Brexit, in which Leave voters are more susceptible to fake news that reflects badly on Remain voters, and vice versa. The effect is also somewhat magnified if participants are first exposed to a threat to their social identity — in this case, as a Leaver or Remainer. In the case of the US, there is a highly polarized political climate which is further heightened at present as it is an election year; that could theoretically enhance the effects of fake news.

She concluded:

We certainly don’t want to state categorically that fake news is not dangerous, but we suspect that real-world behavioral effects will mostly emerge in contexts where individuals seek out many stories all advocating the same position, and which are congenial to the individual’s existing views; anti-vax or climate change denial networks would be a good example of this. What our research strongly suggests is that casual exposure to a novel fake news story is likely to have negligible effects on future behavior.

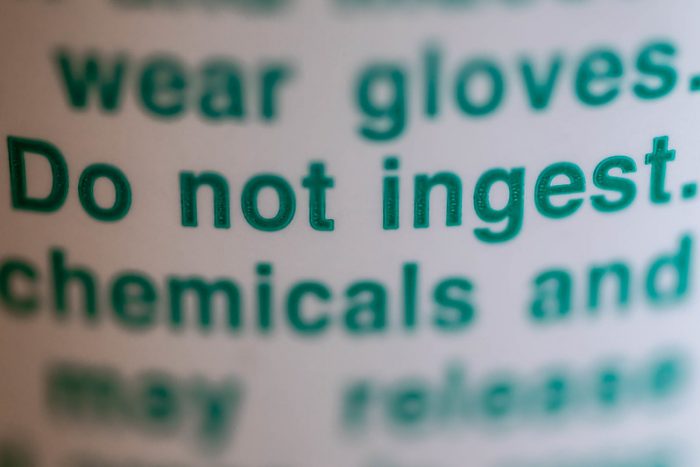

How would this apply to a well-known figure promoting a fake cure? Take, for example, Trump promoting hydroxychloroquine as a coronavirus treatment despite multiple studies showing that it doesn’t work. Or Trump musing that ingesting disinfectant might cure the virus.

“I think it’s really important to recognize the difference between ‘fake news’…as in fabricated stories shared on social media, and inaccurate scientific comments or suggestions from a political leader,” Greene said. “The news that people are hearing in the latter case is not fake. Trump really did suggest that bleach might be curative. It’s just that he was wrong to make the suggestion.”

Even in these cases, though, it’s not clear how many people actually take the president’s advice.

Researchers from Brigham and Women’s found that prescriptions for hydroxychloroquine surged in the U.S. between February 16 and April 25 after Trump praised it as a treatment for Covid-19, causing shortages for patients who actually needed it. It’s unclear, however, how many people who filled prescriptions actually took the medication.

As for reports of increased accidental bleach poisonings this spring, Greene is wary. “Bleach-related accidents in the U.S. had already spiked enormously in the weeks prior to Trump’s comments, simply because people were using much more of than usual to disinfect their homes and workplaces,” she said. By May, the accidental poisonings had fallen sharply, either because people were being more careful with the disinfectants or because they’d simply lost interest in cleaning their homes obsessively. (It turns out deep cleaning probably isn’t all that effective in the fight against Covid-19 anyway.)

“I think it’s a mistake to jump to the conclusion that the change in accident rates is necessarily down to Trump, if for no other reason than the fact that — frankly — most people aren’t that stupid,” Greene said. “People might vote for a leader or espouse support for him for a range of personal or political reasons, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that they treat every word from his mouth as gospel, particularly when it comes to their own health.”