Ed. note: Here at Nieman Lab, we’re long-time fans of the work being done at First Draft, which is working to protect communities around the world from harmful information (sign up for its daily and weekly briefings). First Draft recently launched a publication, Footnotes, and we’re happy to share some Footnotes and First Draft stories with Lab readers. As First Draft executive director Claire Wardle writes, “If the agents of disinformation borrow tactics and techniques from each other, which they do, then so must we.”

Data voids on social networks are spreading misinformation and causing real world harm.

Everyone needs access to credible information during a pandemic. Without it, people die.

We are especially vulnerable when we want to know something — such as how to treat Covid-19 — but no credible information exists. At the beginning of the pandemic, confusion about symptoms, causes, and treatments reigned. Viral posts claimed a runny nose was not a sign of the disease, or that garlic, alcohol, or sunlight were good preventative measures. A range of medicines have been tried and tested, including chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, favipiravir, remdesivir, azithromycin, and dexamethasone. Some were found to be effective, others less so.

If more speculation or misinformation exists around these terms than credible facts, then search engines often present that to people who, in the midst of a pandemic, may be in a desperate moment. This can lead to confusion, conspiracy theories, self-medication, stockpiling, and overdoses.

These invisible moments of vulnerability are known as data voids: when there are high levels of demand for information on a topic, but low levels of credible supply. Data voids were first defined by Michael Golebiewski and danah boyd in 2019, and describe vulnerabilities that emerge from search engines like Google.When it comes to data voids, a distinction is usually drawn between search engines and social media platforms. Whereas the primary interface of search engines is the search bar, the primary interface of social media platforms is the feed: algorithmic encounters with posts based on general interest, not a specific question you’re searching to answer.

It’s therefore easy to miss the fact that data voids exist here, too: Even though search isn’t the primary interface, it’s still a major feature. And with billions of users, they may be creating major social vulnerabilities.

Suggested searches for “vaccine” on Facebook. Screenshot by author.

If we are to respond to information needs as they emerge, and understand whether they are causing harm, we need a way to monitor them.

Important work has been undertaken in this direction. The International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) has visualized its members’ fact-checks related to coronavirus to help us understand where one form of credible information is being supplied. Amazon’s web-ranking company Alexa has created a dashboard to monitor English-language articles relating to coronavirus that have been shared on Twitter and Reddit. Other examples, such as gathers.co, have created a feed of relevant articles. Each of these efforts speaks to a societal need that has yet to be achieved: tracking the flow of credible information in real time.

But while there have been efforts to track the supply of credible information, usually in the form of fact checks or news articles, what we haven’t seen are attempts to bring supply together with demand: what people want to know right now, and what information they’re getting.

First Draft spent recent months building a dashboard to monitor data voids in partnership with the University of Sheffield, looking to find a way to identify where the demand for credible information far outstrips the supply. The results of that research will be published soon, but more urgent is fully understanding the threat these data voids pose to our recovery from the pandemic.

YouTube has famously described itself as “the world’s second most popular search engine.” Despite being a clever marketing tool, the statement is an honest one: People search for information on social media as well as search engines.

With billions of users among them, social media platforms are a primary source of information for many people. But just how much, we don’t know.

Suggested searches for “vaccine” on Instagram (left) and TikTok (right). Screenshot by author.

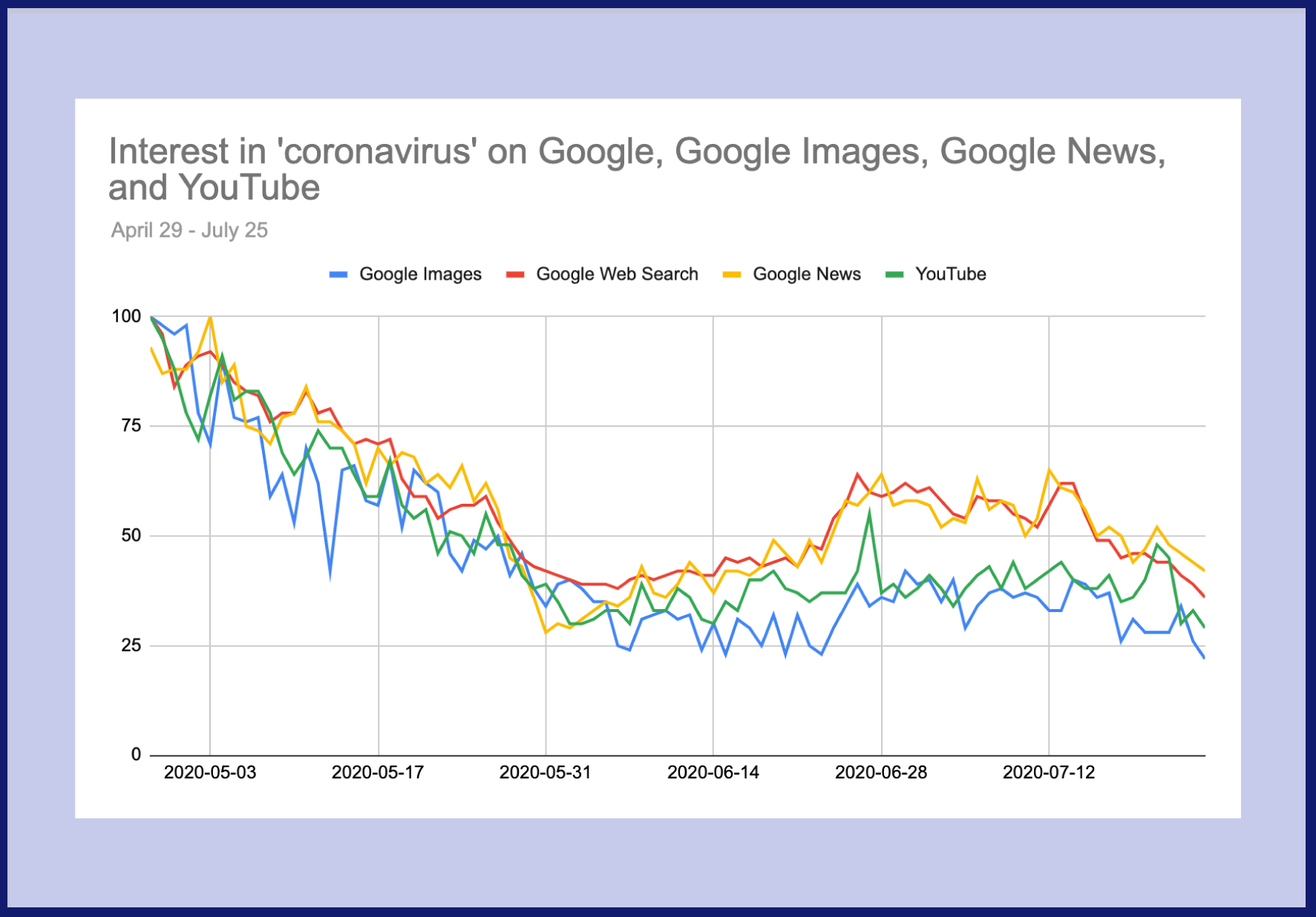

YouTube allows the public to investigate search interest on its platform through a feature tucked away within Google Trends. Given that interest on YouTube fluctuates independently to interest on Google, it’s important for us to monitor both.

Interest in “coronavirus” on Google Images, Google web search, Google News, and YouTube, April 29-July 25. Source: Google Trends. Screenshot by author.

But we have no such picture on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, Reddit and so on. Despite search not being the primary interface of these platforms, it’s clear that, with billions of users, a large part of our picture of data voids is missing.

We have no idea what people are searching for on social media platforms, or what results those platforms are putting in front of people. Clearly, the platforms think search-based misinformation vulnerabilities exist on their platforms, because they intervene in certain search results to promote official information.

However, they don’t provide the transparency to know what people are searching for, how this changes by location, how trends or spikes are emerging in real time, and what information they’re putting in front of people in the search results.

Information about trends and posts on Facebook and Instagram is accessible via CrowdTangle, the Facebook-owned analytics tool that shows which URLs and posts are resonating. Interest can, to some extent, be inferred from this information.

But there are a couple of issues. First, CrowdTangle only covers public posts, which only amounts to a small portion of what’s happening on Facebook. Second, it doesn’t tell us anything about searches on the platform and the connected results.

With billions of users, and likely many more billions of searches, we’re missing a big part of the picture that could be provided without compromising user privacy.

Twitter already has a trends feature, but there is no dashboard to explore multiple locations. You can only see trends in your location as an individual user, or access the data via its API as a developer.

However, Twitter’s API does not provide information on search interest. Trends refer only to popular hashtags and keywords within tweets, giving a picture of what people feel inclined — and able — to express publicly. Seeking information via search is a very different kind of data point, and we need to monitor those searches, as well as what tweets are featuring prominently in the results.

While there are unofficial API wrappers and analytics tools for TikTok, to our knowledge there is no ability to track search trends or results.

Reddit’s API allows users to query trending subreddits, but lacks information on trending searches.

Bing represents 13 per cent of the US desktop search market, which amounts to many millions of users and many more searches. Google has set the standard for search engine analytics, but Bing, Yahoo and Duck Duck Go lack the same transparency.

Google is doing important work on addressing data voids. Not only has it set the standard for search engine analytics with Google Trends, but it also is working on directly addressing data voids with Question Hub, a tool designed to identify “content gaps” and work with fact checkers to fill them. This is important work.

However, a few small changes would greatly improve its effectiveness.

Google Trends should allow Boolean queries. It’s a small change, but a big impact.

First, we’ll be able to more accurately search for a population’s interest in a topic by aggregating interest in terms in multiple languages. In our research into data voids in Greece, we wanted to search for “coronavirus OR κορωνοϊός.” We weren’t able to do this, so we had to use the English term in every country.

Second, we’ll be able to track topics rather than words. Instead of just searching for the word “vaccines,” we could search for:

(vaccines OR vaccine OR vaccination OR vaccinations) AND (unsafe OR injury OR rushed OR OR dangerous OR…)

This would mean we could monitor hesitancy around specific narratives, such as vaccine safety.

Google Search, Google Scholar, Google Alerts and other Google tools already accept Boolean queries. Trends needs to as well.

We need more alerts. We can’t spend all day staring at Google Trends, no matter how fascinating the insights. So we need email alerts when there are spikes and breakouts. Currently, you can only get these on a weekly basis, and often this is too late. We need alerts as and when they occur.

Let’s say lots of people are searching for information about vaccine safety. The next question is: What results are they getting? Which news stories are featuring prominently? Which are being clicked on?

We need richer information about results if we want to be able to determine data voids. A table showing top and rising results for search terms would greatly increase our ability to monitor where people are being sent, and hold platforms to account for the information they expose to their users.

We need different kinds of information as a pandemic progresses. At first we encounter lots of questions about origin. Then we see more claims about remedies and treatments, many of which can cause harm. Eventually, the world turns its eyes to a vaccine.

This is precisely where we’re turning our attention now. It will be critical to monitor the emergent information needs around vaccines and respond to harmful information about vaccines’ safety, morality, freedom, necessity, effectiveness and so on.

We need to track vaccine-related data voids in order to save lives. With changes to Google Trends, we will be able to better track interest in narratives, and direct our responses toward them.

We also need to see social media platforms take action. Early indicators, such as suggested searches for “vaccine” on Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, and Reddit, show what’s possible when we’re unable to analyze search interest, results and voids.

We hope some of these actions can be taken in the coming months as we confront the next chapter in this infodemic: harmful information about vaccination.

Tommy Shane is First Draft’s head of policy and impact. A version of this story originally ran on Footnotes. With special thanks to Pedro Noel, Carlotta Dotto and Rory Smith, who contributed to projects and discussions that led to these recommendations.