No single, authoritative source exists to track evictions in the United States. It can be confusing, even during the best of times, to know how many evictions are happening at any given moment.

It is not the best of times. The pandemic and a patchwork of emergency orders have made the numbers and laws around eviction even harder to keep straight. That’s where Eviction Lab, part of Princeton University, hopes to help.

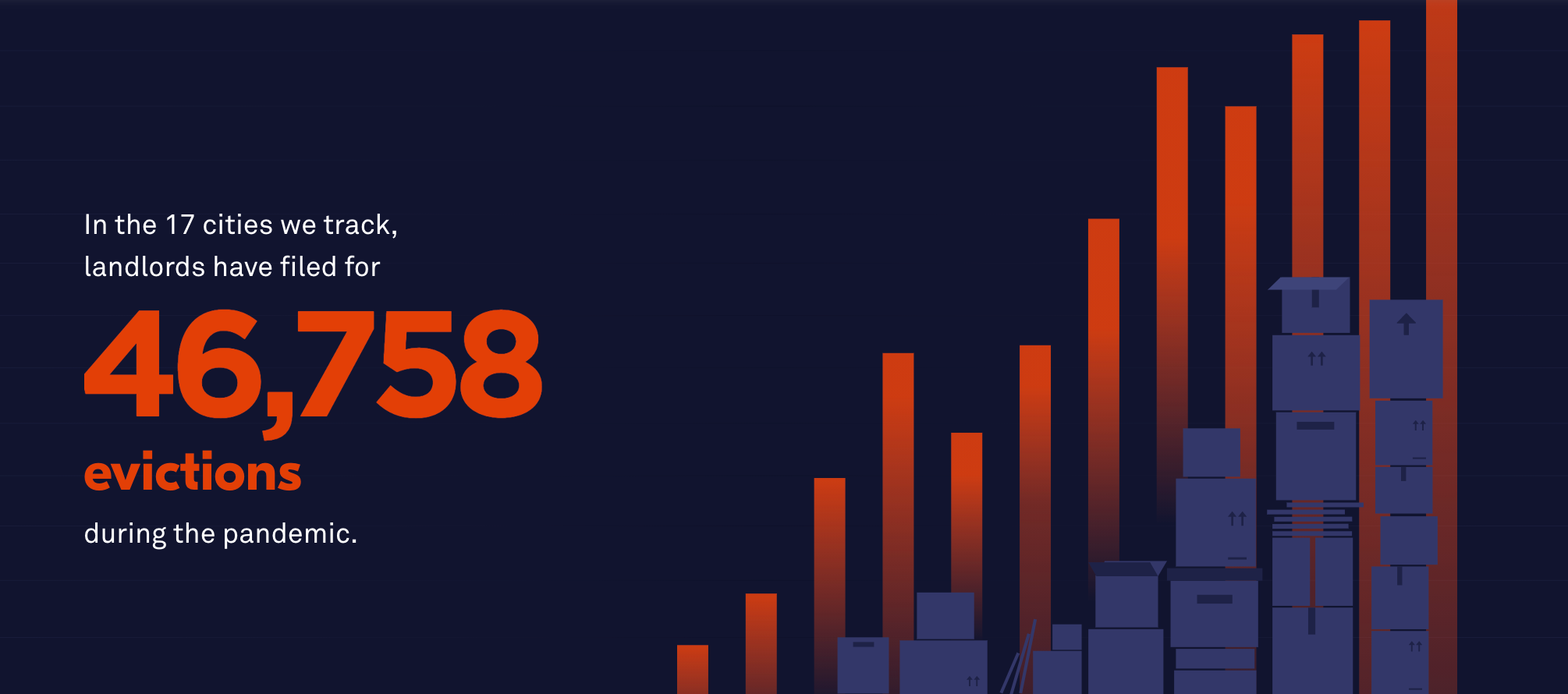

The Eviction Lab maintains a national eviction database and makes the 83 million eviction records they’ve collected available for analysis or merging with other data sources. Their maps and reports are free for publications to customize and embed. As Covid-19 has worsened the housing crisis, researchers have also started live tracking evictions in 17 cities and explaining what various moratoriums, guidelines, and orders actually mean for the nation’s renters.

The imperative to find ways to communicate with the public and share resources with journalists comes from the very top.

Eviction Lab’s founder and director, Matt Desmond, is a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine and his book Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City appeared on bestseller lists before winning the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction — unusual for a fieldwork-based book written by an academic. Desmond, a sociologist by training, captured mainstream attention with vivid writing and a richly detailed chronicle of how evictions often function as a cause, not just a result, of poverty.

As Desmond told NPR this July, the housing crisis is not new:

Every year in America, 3.7 million evictions are filed. That’s about seven evictions filed every minute. That number far exceeds the number of foreclosure starts at the height of the foreclosure crisis. So before the pandemic, the majority of renters below the poverty line were already spending half of their income on housing costs or more. And 1 in 4 of those families were spending over 70% of their income just on rent and utilities.

When you’re spending 70, 80% of your income on rent and the lights, you don’t need to have a big emergency wash over your life to get evicted. Something very small can do it.

Or something very large — like a pandemic.

Since Covid-19 took hold in the U.S., millions of Americans have lost their jobs and many millions more find themselves grappling with insufficient child care and unexpected health care costs. Although Eviction Lab won’t make predictions about the exact number of Americans facing eviction during the spiraling crisis, Desmond has written it’s in the millions. (Emily Benfer, a law professor and Eviction Lab collaborator, estimated 28 million in July and a more recent CNN report put the number around 40 million.)

One of the most important pieces of journalism all year — @KyungLahCNN with the stories of those being evicted and losing their livelihood every day due to the economic stresses of Covid-19.

America is in crisis. Don’t look away. pic.twitter.com/IuBsW5sMm1

— Josh Campbell (@joshscampbell) September 3, 2020

Faculty assistant Anne Kat Alexander said Eviction Lab, in partnership with Benfer, built the Covid Housing Police Scorecard to help reporters parse eviction moratoriums and compare the state-level protections in place for renters.

“The scorecard was filling a pretty media-centric need that we’d seen as various eviction moratoriums were coming out across the country. We sit and look at eviction policy all day — and have for years — so we have an extra level of expertise in interpreting them,” Alexander said.

The scorecard unpacks the policies in each state and ranks them. (If you’re wondering, Massachusetts tops the list with 4.15 stars. Eight states, including Texas and Tennessee, share the bottom spot with exactly zero stars between them.)

Alieza Durana, a policy journalist working at the lab as a “narrative change liaison” through a Chan Zuckerberg Initiative grant, said she splits her time between walking reporters and researchers through resources, making connections to sources or community organizations, and commissioning journalistic work.

“Given that housing insecurity — and particularly the perspective of someone experiencing housing insecurity — has been so underreported in media, part of our grant money from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative goes toward commissioning those works,” Durana said. The works, so far, include “docu-poetry” and reported pieces, and there’s a documentary on the history of eviction on the way.

Eviction Lab acknowledges its database of evictions, though the most comprehensible available, remains incomplete. The federal government and most state governments don’t track evictions, leaving records to be gathered county court by county court. A number of states, because of inconsistent digitization practices and varying privacy and public records laws, almost certainly underreport evictions. And Eviction Lab is only attempting to count the legal evictions. When a landlord changes the locks, turns off utilities, harasses a tenant, or uses other illegal methods to force tenants out, the eviction goes unrecorded.

The Eviction lab media guide says there are “countless untold stories in these data.” Where could you start?

The live tracker is useful for reporters covering one of the 17 cities that it tracks. There’s also data on evictions initiated during the pandemic for relatively small amounts of money — leaving families homeless over a few hundred dollars. Journalists can get the big picture using the database, which includes eviction records from 2000 to 2016, or start collecting their own records for a more updated look.

Durana recommended looking for recurring names on recently filed evictions. “We know there’s often one landlord or a handful of landlords driving a lot of the eviction filings in a place,” she said. “Whether you’re in Milwaukee or Houston or Richmond, starting with PACER or court records is a good way to zero in on what that story looks like.”

Durana noted that some populations are disproportionately affected by evictions due to discrimination in the housing market and policies. Eviction Lab’s maps can be used to investigate where evictions have clustered.

“We know that Black communities, communities of color, families with children, and folks experiencing domestic violence all face high rates of eviction,” Durana said. “It’s something to keep in mind as you report these kinds of stories out.”

For additional information, Eviction Lab recommends connecting with legal aid societies (as New Hampshire Public Radio did for this piece) and organizations (some are listed on Eviction Lab’s sister site, Just Shelter) in your community.