For journalists in 2020, some of the biggest hurdles in getting factual, corroborated information to news consumers are getting to them before the misinformation does or correcting the false information they’ve previously consumed.

Every time something like QAnon or the Plandemic video makes its way to national headlines, I know I’m not alone in wondering how these things got into people’s news feeds in the first place. Who puts these things together and why? Who wins and loses in all of this?

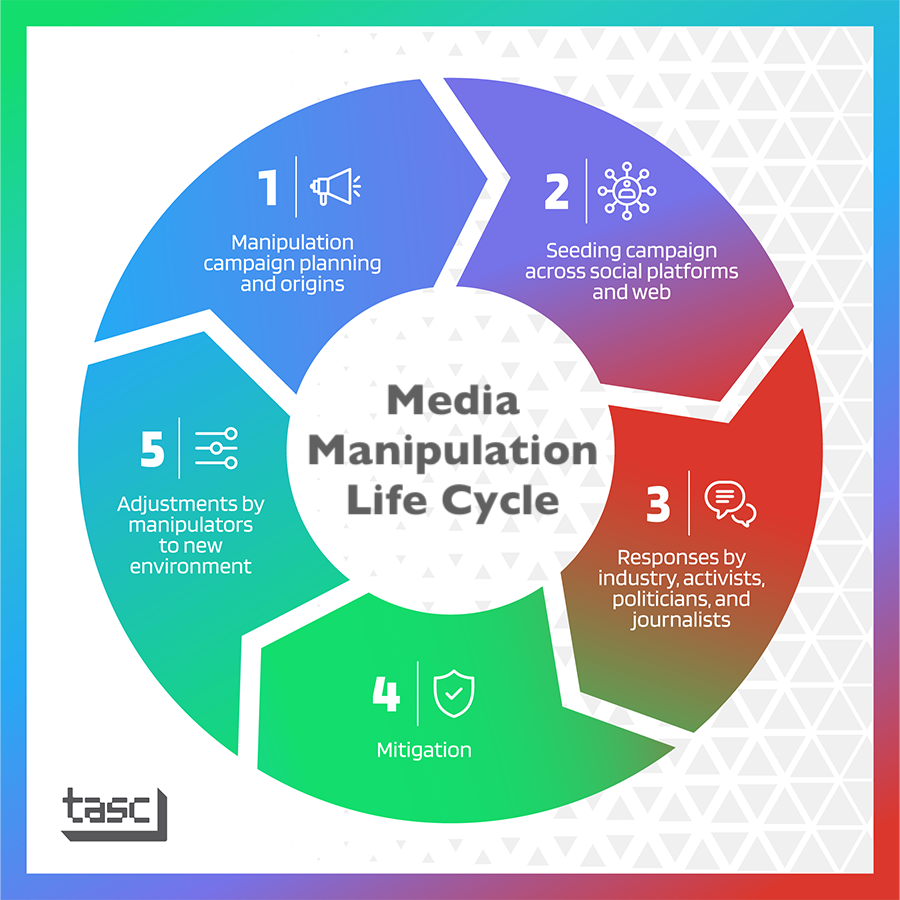

A new project from the Technology and Social Change (TaSC) team at Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Policy wants to help journalists, policymakers, and researchers answer those questions as they move forward in their work. The Media Manipulation Casebook, published Tuesday, is a collection of case studies that break down the evolutions of previous and current misinformation campaigns into five stages. Each case study identifies the order, scale, and cope of the information, who was involved, which platforms were used, what vulnerabilities were exploited, and impacts of the campaign.

The Media Manipulation Casebook team is led by Joan Donovan, the research director of the Shorenstein Center and the director of the Technology and Social Change project.

“We intend this research platform to be both a resource to scholars and a tool to help researchers, technologists, policymakers, civil society organizations, and journalists know how and when to respond to the very real threat of media manipulation,” the researchers wrote in Nieman Reports. “Here, we break down how each stage of the life cycle works, and the ways different groups of people trying to fight back can be most useful. Media manipulation affects not just journalists and social media companies but presents a collective challenge to all of us who believe that knowledge is power.”

One case study that’s ongoing is the amplification of the Plandemic documentary. The trailer for a documentary full of conspiracy theories regarding coronavirus went viral in May 2020. Though media outlets likely covered the story to warn people that the video’s contents were false, they also likely drove people to watch it:

On May 7, BuzzFeed reported on Plandemic and its falsehoods, signifying the conspiratorial video had made it to mainstream media. Moreover, BuzzFeed’s article was shared to Occupy Democrats and 62 other Facebook pages — introducing Plandemic to groups who may not have seen it yet.

The Atlantic, NPR, Wall Street Journal, Science, and BBC News are among the publications that published Plandemic articles within the first week of its release. Advocacy groups — including global health, pro-vaccine, and pro-science groups — also covered Plandemic.

As word (and links) continued to spread, NBC News reported that Plandemic “has been shared by celebrities, including the comedian Larry the Cable Guy, NFL players and Instagram influencers with millions of followers.” In the same article, George Washington University’s David Broniatowski discussed Plandemic’s resonance — and hazard — across normally unaligned groups: “The danger with movies like this is that they can weave all of the disparate streams into a common narrative, building a coalition for political and collective action, even when the reasons for this coalition aren’t universally shared.”

Another case study looks at the “Endless Mayfly Network” from 2016 to 2018, when websites with false and inflammatory information about the Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Israel were created to look like real, credible news outlets. The stories were picked up and falsely reported on by mainstream news outlets and ultimately, the conclusion was that the initiative was operated by an “Iran-aligned” group.

Read more about the project in Nieman Reports here.

Friends, we made you something. It’s called The Media Manipulation Casebook.

The Casebook is a database to make sense of the chaos of this era, to help you understand how to detect, document, and debunk media manipulation. https://t.co/Yibcm8OvyO

— Emily Dreyfuss (@EmilyDreyfuss) October 20, 2020

The new Media Manipulation Casebook from our friends at the @ShorensteinCtr‘s Technology and Social Change project includes theory + methods for those studying & reporting on online political communication + misinformation.

Check it out:https://t.co/ocVKgRd35R

— Journalist’s Resource (@JournoResource) October 20, 2020

The @ShorensteinCtr came out with their “Media Manipulation Handbook” that discusses how disinformation populates throughout the media (and is very much in line with my advocating for not interacting with disinformation posts as it boost the disinfo) read: https://t.co/TmDPZwPb2o pic.twitter.com/xq8IdUlOIv

— Maya Contreras (@mayatcontreras) October 20, 2020