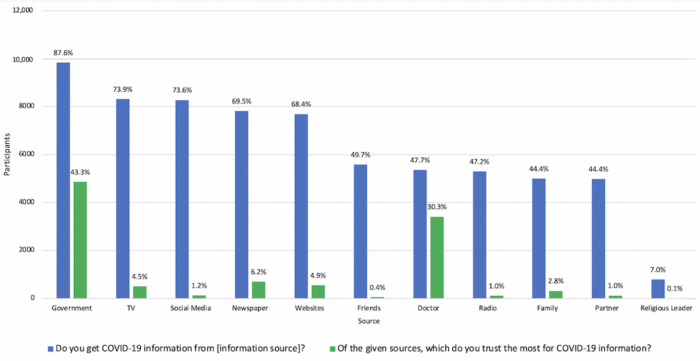

Where did you hear that? A new study found that though people often turn to traditional media sources — 91% reported getting information about Covid-19 from newspapers, TV, or radio — they’re also paying attention to multiple other sources, including government websites, friends and family members, and social media.

The study, by researchers at NYU’s School of Global Public Health, found that people use six different sources, on average, to gather information about Covid-19 and that the numbers were higher earlier in the pandemic, when the novel coronavirus was, well, more novel.Those with children and with college degrees used more sources, while those who were male, aged 40 and older, not working or retired, or Republican tended to rely on fewer sources, the study found.

The results prompted the researchers to advocate for “targeted health communication campaigns” to reach men, older U.S. adults, and those with a high school diploma or less in education.

Men were significantly less likely than women to use all identified sources, with the exception of religious leaders and interpersonal connections like family and friends. The authors suggest this could be one reason why men are less likely to comply with social distancing and other practices encouraged by public health experts:

Findings that men were less likely to use almost all of the identified information sources, used fewer sources in general, and were also less likely to trust government websites for Covid-19 information suggest significant sex disparities in Covid-19 information source utilization. This evidence corresponds with other preliminary research observing that men are less likely to abide by advocated COVID-19 health behaviors, and that young men are more likely to agree with Covid-19 myths and underscores the need for a sex-based targeted COVID-19 health information communication strategy.

Overall, the respondents — about 11,000 adult Facebook users in the United States — were less likely to use any source in April compared to just a month earlier. In particular, researchers saw dramatic drops in those turning to government websites and those choosing government websites as their most trusted source; the latter dropped from 53% in March to 37% percent in April. (You might remember there was a strong push by tech platforms like Facebook, Google, and Twitter to direct users to official government websites in the early days of the pandemic.)

The use of government websites and mainstream media were associated with an ability to correctly answer questions about Covid-19. But which mainstream source of information mattered:

Although social media often gets cast as the misinformation bogeyman, the study found the use of social media was associated with increased awareness of one of seven Covid-19 knowledge questions and had no effect on the other questions. (Those who trusted social media information the most, compared to those who said government websites were the most trustworthy, however, displayed reduced knowledge for two questions.) “These insights suggest that certain sources of information may not inherently result in compromised awareness of information pertaining to a health crisis, but other factors, such as the actual content, how the source is used by an individual, and the specific knowledge being assessed, may all play a relevant role in determining disparities in knowledge,” the study’s authors concluded.When adjusted for sociodemographic variables, total number of sources, and the most trusted source of information, those relying on CNN were more likely than those relying on other local/national media sources to correctly answer 2 of the 7 questions, while those relying on Fox News were more likely to incorrectly answer 3 of the 7 questions …

Compared to those relying on other national/local media, those relying on CNN or MSNBC were more likely to agree that the coronavirus is deadlier than the seasonal flu, the amount of media attention devoted to the coronavirus has been adequate, and the coronavirus is a bigger problem than the government suggests. In addition, they were more likely to disagree that warmer weather will reduce the spread of the coronavirus and that the coronavirus is not as big of a problem as the media suggests. Conversely, those relying on Fox News were more likely to agree that the coronavirus was released as an act of bioterrorism, warmer weather will reduce the spread of the coronavirus, and the coronavirus is not as big of a problem as the media suggests. In addition, they were more likely to disagree that the coronavirus is deadlier than the seasonal flu, the amount of media attention devoted to the coronavirus has been adequate, and the coronavirus is a bigger problem than the government suggests.

The lead author, Shahmir Ali, a doctoral student at NYU School of Public Health, told me the field’s standard information source categories (“social media” vs. “mainstream media,” for example) were “formulated from past research done at a time of less complexity in how we receive information.” CNN, he noted, can be watched on TV but also has a website and active social media presence — all of which participants can use to gather information. You can read the full study, published in JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, here.

Excited to share new #COVID19 research published with @tozan_yesim and my great @nyupublichealth team. In this paper we provide some of the first insights into COVID19 information sources – who is using what, who is TRUSTING what. Some findings below: https://t.co/VrxlWLLnR9

— Shahmir H. Ali 🇦🇺🇵🇰🇺🇸(🇨🇳) (@shahmirhali) October 8, 2020