For some completely unknowable reason, a lot of people are interested these days in why Americans sometimes get the most damn-fool ideas in their heads about politics. What leads people to believe fantastical claims of imaginary voter fraud, say, or that the Democratic Party is run by a league of Satanic cannibal pedophiles?

There’s plenty of blame to go around: political leaders happy to embrace politically convenient lies; partisan media optimized for inflammation; social platforms that reward the outlandish and false over the boring and true.

But one popular suspect going into 2020 was technological: deepfakes. Originally invented for porn, deepfakes are like Photoshop for videos, letting one person’s face be realistically applied to another’s body or making it appear that someone is saying words they’ve never uttered. The fear was that a deepfake could convincingly make candidates seem to say outrageous things that would poison voters’ opinion of them.(Imagine Joe Biden “saying” that half of white people’s salaries should be garnished to fund Black Lives Matter protests. Or Donald Trump saying…well, you don’t have to imagine.)

But deepfakes didn’t play the role some imagined/feared in the election. Truly convincing deepfakes are still relatively difficult to produce, and there are so many less labor-intensive ways to lie creatively — from the basic video edits sometimes labeled cheapfakes to a Facebook meme with a made-up quote Canva’d onto someone’s photo.

And a new study finds that — even if we had seen a swarm of deepfakes — they probably wouldn’t have been any more effective at making people believe false things than other, simpler tools in the fraudster’s toolbox.

The paper, now out in pre-print, is by Soubhik Barari, Christopher Lucas, and Kevin Munger (of Harvard, Washington U., and Penn State, respectively). Here’s the abstract, emphases mine:

We demonstrate that political misinformation in the form of videos synthesized by deep learning (“deepfakes”) can convince the American public of scandals that never occurred at alarming rates — nearly 50% of a representative sample — but no more so than equivalent misinformation conveyed through existing news formats like textual headlines or audio recordings.Similarly, we confirm that motivated reasoning about the deepfake target’s identity (e.g., partisanship or gender) plays a key role in facilitating persuasion, but, again, no more so than via existing news formats. In fact, when asked to discern real videos from deepfakes, partisan motivated reasoning explains a massive gap in viewers’ detection accuracy, but only for real videos, not deepfakes.

Our findings come from a nationally representative sample of 5,750 subjects’ participation in two news feed experiments with exposure to a novel collection of realistic deepfakes created in collaboration with industry partners. Finally, a series of randomized interventions reveal that brief but specific informational treatments about deepfakes only sometimes attenuate deepfakes’ effects and in relatively small scale.

Above all else, broad literacy in politics and digital technology most strongly increases discernment between deepfakes and authentic videos of political elites.

In other words, deepfakes are a threat to political knowledge — but not a particularly distinct one from all that came before.

Researchers presented two sets of media to a representative online sample of 5,750 people. The first featured something like a Twitter or Facebook feed, filled with real politics stories and one item about an alleged scandal; for some subjects, that scandal was presented via a deepfaked video. The second included eight news videos — some real, some fake — and asked people to figure out which were which. The first experiment attempted to replicate the sort of environment in which a deepfake would likely spread: a social media feed, where it’s one item surrounded by other “normal” content. The second pushed people to be more evaluative of each video, which should trigger some additional effort at discernment.

I can’t tell you how delighted I am to let you know that this paper includes the phrase “professional Elizabeth Warren impersonator,” which is apparently a real job and not just a common trope in Harvard-faculty-party fanfic. Yes, the scandals in the first experiment all focused on the Massachusetts senator saying some awful (or at least out-of-character) thing:

We produced a series of videos performances of the impersonator in a similar kitchen performing several different sketches that each represented a potential “scandal” for Warren. To script these scandals, we carefully studied past controversial hot mic scandals of Democratic politicians as well as exact statements made by Warren in these campaign videos. We then scripted statements in Warren’s natural tone and affliction that appeared plausible in the universe of political hot mic statements. As such, these statements are not meant to invoke extreme disbelief or incredulity, though testing the credulity threshold of deepfake scandals in a principled manner could the subject of future research.

Each of these scandals was presented to subjects either through a deepfaked video, faked audio (from the impersonator), an SNL-style skit (in which the impersonator is shown to be an impersonator — think Alec Baldwin playing Trump), a text headline. Some subjects got no fake scandal but were shown a real anti-Warren attack ad; the control group got none of the above.

So, what did they find?

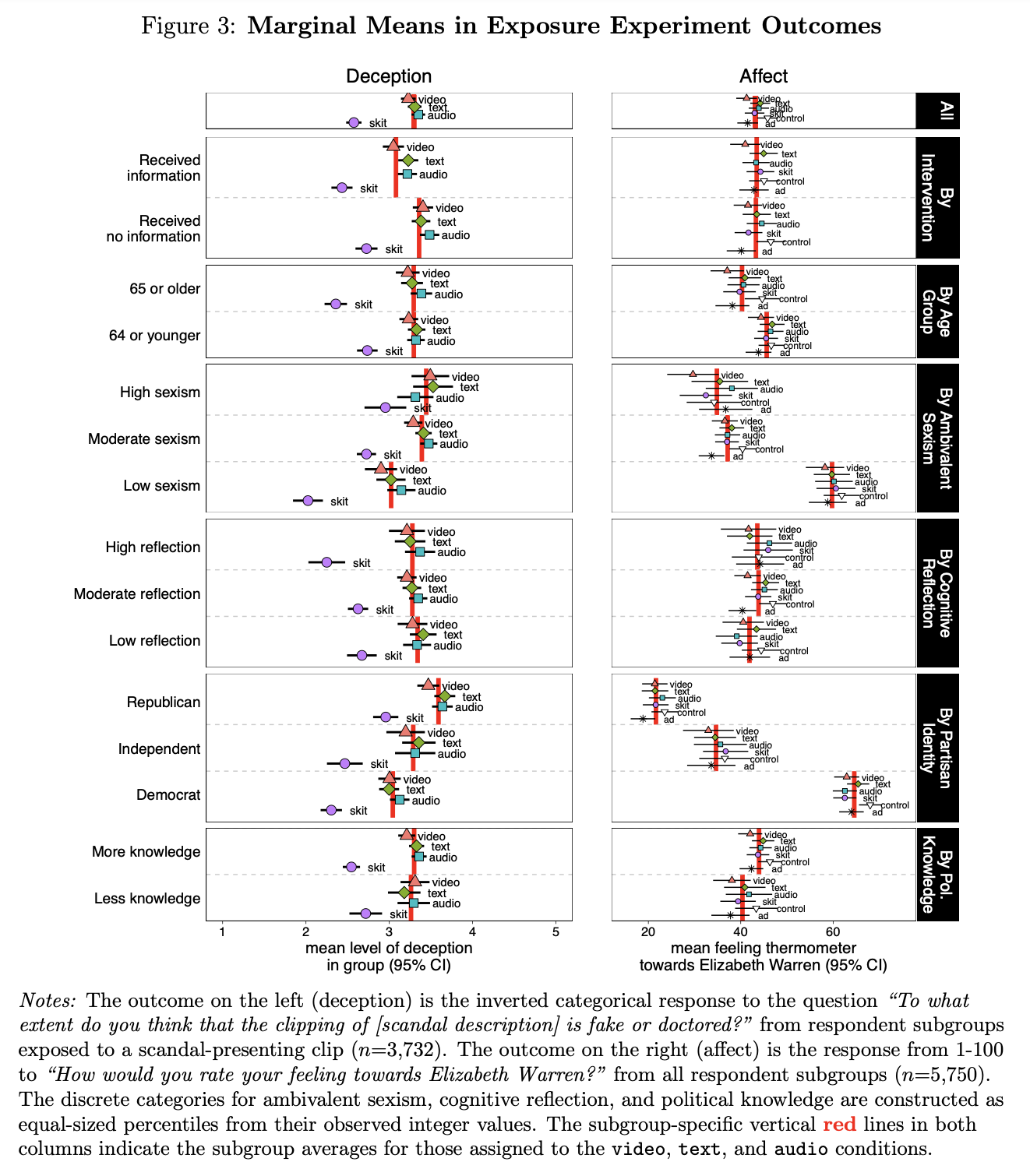

Our deepfake videos — with an average deception level of 3.22 out of 5 or 47% of respondents who are more confident the clip is real rather than not — were statistically no better at deceiving subjects than the same information presented in audio (3.34 or 48%) or text (3.30 or 43%)…The inclusion of the skit of our Warren impersonator doing her best performance without deepfaking provides a baseline to compare these numbers against (2.57 or 30%)…In absolute terms, just under half of subjects were deceived by the best-performing stimuli. Table F5 and Table F6 show that these differences are robust to a variety of model-based adjustments.Relative to no exposure, videos do increase negative affect towards Elizabeth Warren as measured by the 0-100 feeling thermometer (∆ = −4.53, t = −2.79, p < 0.01). However, there are demonstrably null effects of the deepfake video on affect relative to text (∆ = −2.94, t = −1.84, p = 0.06) and audio (∆ = −2.64, t = −2.64, p = 0.09)…

In other words, sure, the deepfakes led 47 percent of subjects to think the imaginary scandal was probably real. But audio alone did slightly better (48 percent) and both did only a hair better than a simple fake headline (43 percent). And those who saw the deepfake didn’t think any worse of Warren than those who just read a headline.

The researchers sliced and diced the results across a variety of factors — subjects who had more or less political knowledge, who were more or less sexist, who had lower or higher levels of cognitive reflection — and the results were pretty meh across the board.

Some of the subgroup factors affected how likely it was that the scandal was believed; for instance, Republicans and high-sexism subjects were more likely to believe the fake Warren scandal than Democrats and low-sexism subjects. But within these groups, the differential impacts of deepfake vs. text vs. audio were tiny.

(Interestingly, those with “high” and “low” levels of political knowledge were about equally likely to believe the fakery.)

Altogether, the exposure experiment furnishes little evidence that deepfake videos have a unique ability to fool voters or to shift their perceptions of politicians. In fact, the audio condition had the largest average deceptive effect, though the difference is statistically insignificant relative to video in all but two subgroups; some models that estimate adjusted marginal coefficients of deception for each group find this difference to be significant.

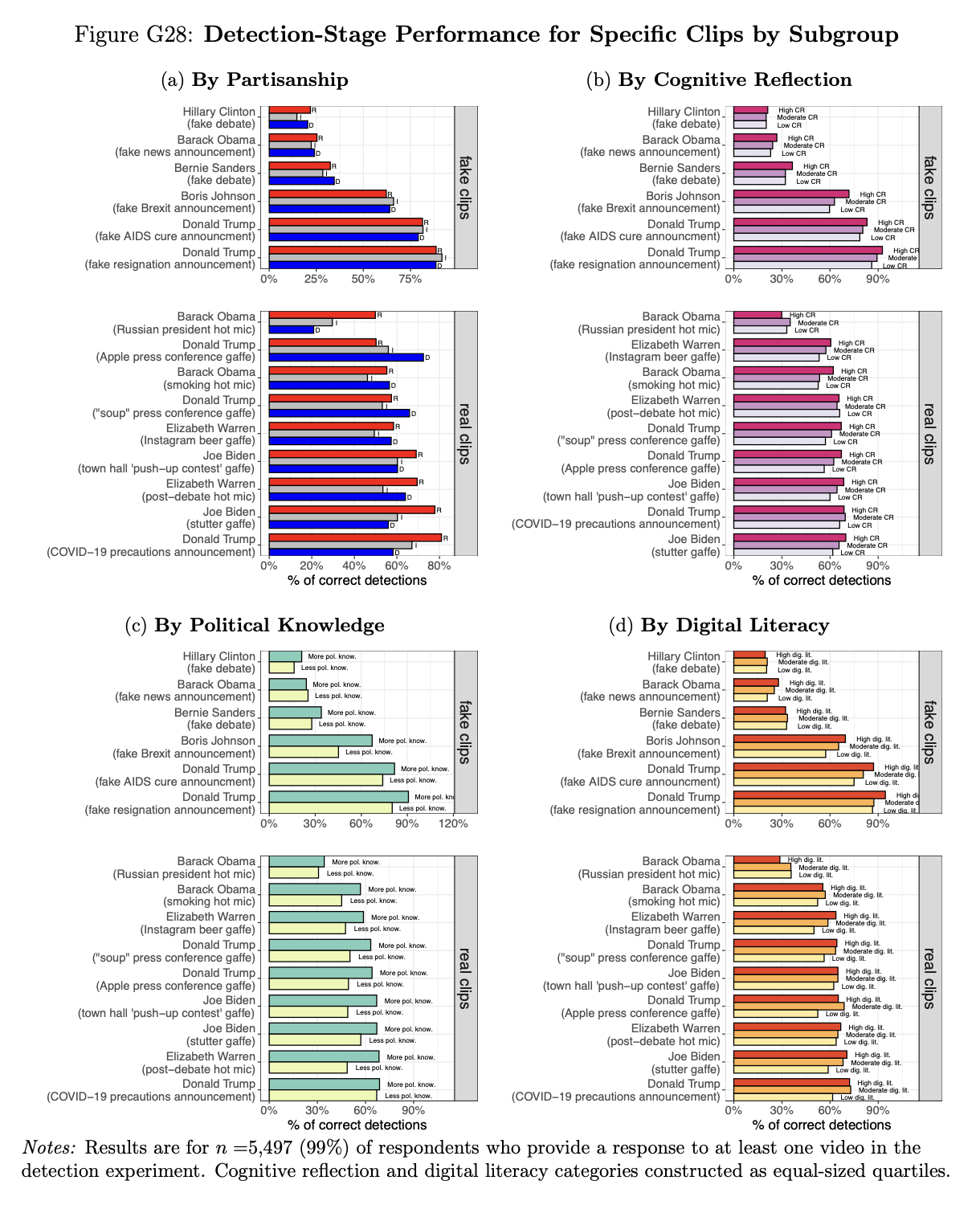

What about the other experiment, the one where subjects were asked to figure out which videos were fake and which were real? Overall, people picked correctly on 55 percent of videos — which isn’t great! Here, those with higher levels of political knowledge and higher levels of digital literacy fared substantially better in separating the gems from the fugazis.

But it’s another result from that experiment that, I think, shows the real problem with deepfake fear-mongering. Both Republicans and Democrats were much more likely to declare a real video “fake” if it makes their political side look bad.

Digital literacy, political knowledge, and cognitive reflection bolster correct detections roughly evenly for all clips. However…partisans fare much worse in correctly identifying real, but not deepfaked, video clips portraying their own party’s elites in a scandal.58% of Republicans believed that real leaked footage of Obama caught insinuating a post-election deal with the Russian president was authentic compared to 22% of Democrats, a highly significant differential…The numbers are flipped for the clip of Donald Trump’s public misnaming of Apple CEO Tim Cook which was correctly identified by 87% of Democrats, but only 51% of Republicans…

Perhaps most striking is that for an authentic clip from a presidential address of Trump urging Americans to take cautions around the COVID-19 pandemic, the finding holds in the opposite direction: it is a positive portrayal, at least for Democrats who by and large hold similarly cautionary attitudes towards COVID-19, yet only 60% of Democratic viewers flagged it as authentic whereas fully 82% of Republicans believed it to be real.

Partisan motivated reasoning about the video target’s capacity for scandal does explain video misdetection, but this operates through discrediting real videos than rather believing deepfake videos. This particularly striking given that, at the time, these real events and their clips made headlines with left- and right-leaning news outlets and, in some cases, became viral on social media, which we would expect to universally boost their recognizability.

This is both why our information ecosystem is a disaster and why deepfakes aren’t as bad as people feared.

How partisans view a particular piece of media isn’t driven by some cold, clinical evaluation of the evidence. If you like Obama and you see a video clip that seems to make him look bad, you’re more likely to think it’s not real. And if you like Trump, same thing. And the same is true for the memes your uncle shares on Facebook, the rants Tucker Carlson gives on Fox, and whatever your favorite #resistance tweeter is tweeting. The specific details of the piece of media get contextualized into our existing beliefs.

And, the researchers found, the impact of that phenomenon is greater on how we think about real videos than how we think about fake ones. Republicans and Democrats faired almost identically well in evaluating fake videos — but both underestimated the authenticity of real ones that seem to go against their side.

I’d argue that this justification-via-contextualization isn’t always unfair. Not to get all postmodern on you, but “authenticity” is one axis on which to measure the truth of a piece of media — but it’s not the only one.

While the subjects here were being asked about whether a particular video was “real” or “fake,” I’d wager that the more committed partisans on both sides were also asking themselves a more nuanced question: Is this video a fair and accurate reflection of reality in its totality?

Here’s what I mean. A Democrat who sees a video in which Trump promotes COVID caution might think that — while it’s a real clip of a real speech — one moment is hardly representative of the many months and many ways in which he minimized the threat, declared COVID would “go away soon” on its own, and so on. It’s an authentic piece of media, but if you’re trying to understand Trump’s performance during the pandemic, it brings you farther from the truth, not closer.

Or she might see the clip of Obama talking with the Russian president and think that, even though it’s a real video, it was also blown way out of proportion for partisan purposes — and was hardly equivalent, as some conservatives would later argue, to the Trump campaign’s repeated dealings with Russia.

Or, after watching a clip the researchers describe as “Joe Biden (stutter gaffe): A video compilation of Joe Biden stuttering in various campaign appearances,” a Democrat might think that, even if all the clips in the video are real, the purpose of editing them together is to suggest that Biden is a doddering old senile man, which is neither fair nor reflective of reality.

To be clear, this can go in both political directions. A Trump supporter seeing a video of him calling Apple CEO Tim Cook “Tim Apple” might generate the same reaction a Biden fan had to the stuttering video: It’s a real piece of media, yes, but it’s also a simple slip of the tongue that was blown up by his opponents into something more profound. Or they might see a video of Trump claiming some of last summer’s protesters were throwing full cans of soup at police and think: Look, some were throwing full cans of garbanzo beans, close enough, quit hassling Trump over it.

In each of these cases, the partisan’s evaluation of a news video includes an evaluation of how it will be weaponized by others. After all, each of the real videos shown to subjects here was also the jumping-off point for thousands of tweets, dozens of takes and cable-news segments. Otherwise, it’s a bit like being asked to evaluate a gun without considering who’s firing it at whom.

Think of it as the difference between calling a particular piece of media fake and calling it bullshit. And “things that are accurate but also bullshit” is a big share of what gets lumped into the all-encompassing category of “fake news.”

Some parts of journalism have come around to the idea that true/false isn’t a binary — that there are also true statements presented in misleading contexts, inaccurate statistics used to support accurate claims, and every variation thereof. Fact-checkers acknowledge that, somewhere in the land between True and False lie Mostly True, Half True, and Mostly False. A statistic that sounds horrifying on its own might be comforting when put into the right context. And the past four years have certainly taught a lot of reporters that accurately quoting what the president says is often in conflict with bringing truth to your readers or viewers.

In all of these cases, it’s hard to separate the evidence from the larger argument it’s being used to advance — and that entanglement can be used for good or ill, to enlighten or to confuse, and to promote any politics from left to right. But when it comes to deepfakes, it’s easy to get stuck in that binary.

This is why deepfakes aren’t as big a deal as some people worried. This new technology is pretty good at creating a digital artifact that is false but seems, at some level, true. But so is a Twitter account and a keyboard — and so is a cable news network with 24 hours to fill. QAnon has driven millions of people into some truly insane beliefs with no technology more complicated than an imageboard and a few thousand paranoid villanelles.

We were surrounded by bullshit before deepfakes, and we’ll be surrounded by bullshit after making a good one only takes two taps on your phone. The good news is that deepfakes don’t seem to present more of a danger than other varieties of disinformation. The bad news is…that’s plenty bad enough.

That’s the end of my article — but dear reader, will you allow me a brief methodological sidebar? Specifically: I really wish researchers creating fake news products for use in experiments were better at making them look like real news products.

I’ve complained before about studies that present subjects with made-up “news” sites in order to measure reader response — but which make the sites look so unlike actual news sites that, imho, it hurts the reliability of the results.

I swear I've seen a half-dozen studies over the years where they created a "news site" to use for experimental purposes and man, they are all aggressively ugly to a degree I honestly think might impact the results.

Like, I would trust a news site that's this unpleasant less! pic.twitter.com/rnAUI08p5g

— Joshua Benton (@jbenton) July 18, 2018

In this study, as in others that use altered cable-news video, the “realness” or “fairness” of a segment is affected by little things like chyron typography that can make an image feel somehow off. Like this fake CNN chyron, which features way too much padding on left and right (the “B” in Breaking and “T” in Trump should be flush), a random extra space before the colon, and smart quotes where CNN uses dumb ones:

Or this one, which uses a typeface that doesn’t look much like Fox News’, is too thin a weight for TV, and has a space missing after the colon:

Maybe I’m being a little design-picky, but I think any regular viewer of these news networks would be sufficiently aware of its design language to know that something’s wrong here. And given that the whole idea here is for subjects to judge whether a piece of media is real, nailing the details is important.