At the beginning of the pandemic (remember the beginning?) it seemed as if every news outlet in existence was launching its own coronavirus newsletter to share breaking news and analysis as it came out.

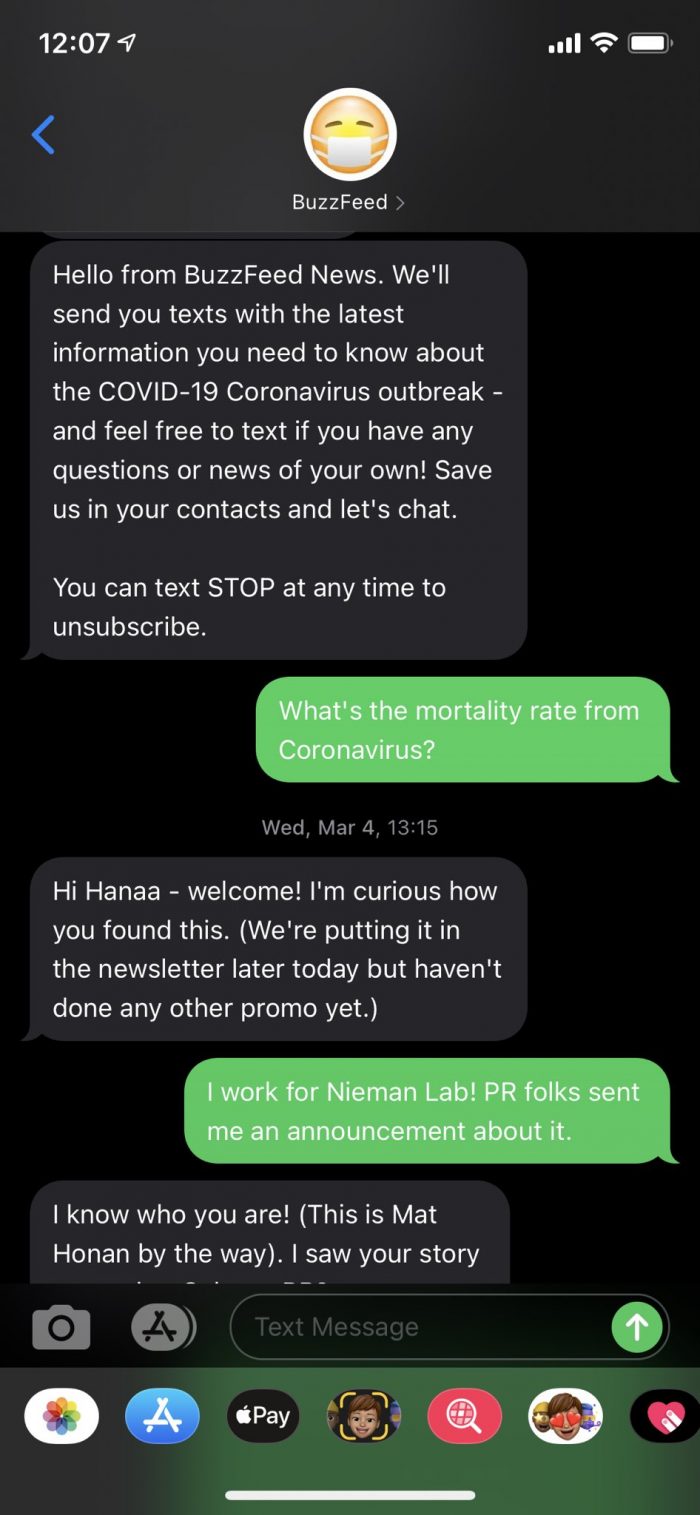

Some sites tried different platforms instead — like SMS text messaging. For instance, BuzzFeed News’ executive editor for technology and society, Mat Honan started using Subtext, a subscription messaging platform that allows organizations to text with their audiences, as a way to answers reader questions about the virus. I signed up to test it out.

Subtext launched in 2019 under Alpha Group, the in-house tech and media incubator owned by media company Advance. Mike Donoghue, the co-founder and CEO of Subtext, said it was developed to give people a way to build meaningful relationships with their audiences.

“Media companies were investing a huge amount of time, money, and effort in building out these huge audiences on social media…but at the end of the day, they’re renting those audiences from social media [companies], as opposed to owning those relationships,” Donoghue said.

Text messaging, meanwhile, was appealing because it’s not a heavy tech lift and it’s more conversational.

“We looked at the newsletter ecosystem, like Substack or Revue or Tinyletter. [But] we wanted to make sure that the dialogue here was bilateral,” Donoghue said. “We didn’t want to create another platform where a media company or a journalist is just kind of talking at their audience. We wanted to make it participatory and we wanted to make it simple to use. We decided that SMS was actually a really, really good medium.”

Subtext certainly isn’t the first initiative to see the appeal in news organizations texting readers. A couple years back, news organizations experimented with using Facebook Messenger to let readers text bots. (It didn’t catch on.) Other early experiments included the texting platform Purple, which was acquired by The Skimm in 2019. Outlier Media pioneered a local-journalism-via-texting service that connected low-income residents with helpful information about issues like housing and utilities.Subtext differs in that it’s a platform offering texting as a tool for news organizations.

The privacy of texting means users don’t experience the same toxicity or endless doomscrolling that you would on social media, making it a friendlier and healthier interaction. Donoghue said that overall, only one person has ever been removed by a host as a subscriber for misusing the platform.

It also allows users to get to know and form a bond with the journalist or personality on the other end of the line. The bond can be strong enough that some people feel bad unsubscribing.

“I can’t tell you how many emails we get, that are like, ‘Hey, I have to unsubscribe but please don’t tell the host,'” Donoghue said with a laugh. “I think it’s a testament to the personal connection that people are making here. I’ve never felt really guilty about unsubscribing to an email newsletter. And I certainly wouldn’t feel guilty about unsubscribing to a digital media subscription.” Subtext’s overall subscriber churn is low — just 2%, Donoghue said. (This may be because texting with a news organization is still fairly novel. If it’s widely adopted by news organizations, the texts could become as easy to tune out as push notifications and email newsletters.)

More than 500,000 people are subscribed to at least one of 600 hosts using Subtext. Hosts can use it in a variety of ways: as an engagement campaign that’s free to subscribers, to get them more interested in the publication or personality; as a retention campaign that’s offered for free to paying subscribers; or as a paid individual subscription to receive messages from one person or about a subject matter someone is particularly interested in.

Pricing varies depending on who the host is and whether they’re charging users for the texts. Organizations (which might or might not be news outlets) that use Subtext to run “retention or engagement campaigns — those made free to the public or free to subscribers of another digital subscription product” pay a fee starting at a “couple hundred dollars a month,” Donoghue said.

Publications that provide the texting service for free purchase a license from Subtext, with the price varying based on the number of subscribers or messages sent. And publications that charge subscribers a monthly fee for texts agree to a revenue share with Subtext, where the outlets retain 80 percent of the revenue.

Data privacy is one of Subtext’s core tenets. Any subscriber data that’s collected (like phone numbers and emails) is owned by the host and can be exported if they leave the service.

Subtext is also unable to see who individually opens a text message because that information doesn’t get communicated back from the cell carrier, though it can show an average open rate. Donoghue said that 92 percent of messages get opened, and 85 percent get opened within the first hour that they’re sent. Reply rates are one of Subtext’s key metrics because they show that a subscriber was invested enough in the message they received to open up a conversation.

News outlets are using Subtext in several different ways. BuzzFeed News used it as a pop-up feature, but other news outlets, like NPR, use it to inform their podcasts. Podcast fans can text the hosts with their feedback and let them know what they’d like to hear in the next episode.

At The Arizona Republic, director of audience innovation P. Kim Bui used Subtext to answer coronavirus-related questions. When Gannett announced staff furloughs, Bui texted users to let them know why they might not be hearing from her as frequently, and asked them to subscribe to the paper.

I got this note today from one of our @Subtext folks. This is better than the pick-me-up I get from coffee: “I wanted to say thank you for everything you guys have been doing to keep the public informed. You guys are as much heroes as the medical personnel on the front lines”

— P. Kim Bui (@kimbui) April 5, 2020

The Globe and Mail uses Subtext to send out recipes. The Dallas Morning News offers a mix of paid and free texting subscriptions — users can get roundups of the day’s headlines for free, or pay $3.99 per month to text with the paper’s Dallas Cowboys reporters.

“If you’re going to create a community, you’ve got to optimize for the relationship, as opposed to optimizing for email conversions,” Donoghue said. “We look at [the newsletter] space and we’re like, we’re gonna get to the point of like total newsletter saturation. Where do we go from there? We think a deeper, more meaningful interaction and communication tool is really beneficial.”