That 2014 Innovation Report was written by 10 white people and does not mention the words “diverse,” “diversity,” “racial,” or “race” once. In 2014, as the paper recognized that growing its audience and was crucial to its survival, it did not, in this report, recognize that readers and staff members of color were a key part of that mission. The 97-page report mentions race exactly once, in an aside about how reporters use social media (“Jon Eligon wrote a gripping first-person account on Facebook about his experience as a black reporter approaching a white supremacist in North Dakota”). The report does not include a single photo of a Black employee.

Another report, “Journalism That Stands Apart: The 2020 Group,” was released, publicly, in January 2017. This time, the report acknowledges that “increasing the diversity of our newsroom — more people of color, more women, more people from outside major metropolitan areas, more younger journalists and more non-Americans — is critical,” and it includes a couple relevant quotes from newsroom employees: “The Times should invest more in career planning, and should do more to not only hire people of color or people who aren’t from the usual talent pipelines but also help them with mentorship and career advancement,” and “We need more diversity at the top, in the traditional sense and in the sense of diversity of skills.”Four years later — and following the high-profile resignations of reporter Donald McNeil Jr. (for using a racial slur) and opinion page editor James Bennet (for running an op-ed by Senator Tom Cotton that called on the military to quash Black Lives Matter protests), The New York Times on Wednesday released a report, “A Call to Action: Building a Culture that Works for All of Us,” that brings race in the newsroom front and center. “Without following through on our commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion internally, we will inevitably speak to and reach only certain readers through our journalism,” the report’s authors Amber Guild, president of T Brand; Carolyn Ryan, deputy managing editor; and Anand Venkatesan, SVP of strategy and head of operations, write. “We want a subscriber and readership base that more fully reflects the breadth of the society we serve.”

As Nieman Lab did with both the 2014 and 2017 reports, we’ve pulled out some key passages from the new report.

The report’s stated focus is on “what isn’t working, and what we will do about it.”

There’s been some progress. The percentage of people of color at the company has increased slightly since the end of 2019 when the Times last made figures available (from 32% to 34%).After several months of interviews and analysis, we have arrived at a stark conclusion: The Times is a difficult environment for many of our colleagues, from a wide range of backgrounds. Our current culture and systems are not enabling our workforce to thrive and do its best work.

This is true across many types of difference: race, gender identity, sexual orientation, ability, socioeconomic background, ideological viewpoints and more. But it is particularly true for people of color, many of whom described unsettling and sometimes painful day-to-day workplace experiences.

We heard from many Asian-American women, for example, about feeling invisible and unseen — to the point of being regularly called by the name of a different colleague of the same race, something other people of color described as well.

We found that our Black and Latino colleagues face the largest and most pervasive challenges. Black and Latino people are notably underrepresented in leadership — compared with the company over all, and to the country. Black colleagues who are not in leadership positions leave the company at a higher rate than white colleagues. Black employees, and Black women in particular, rated the company lower across nearly all categories of our 2020 employee survey, with the lowest scores around fairness and inclusion.

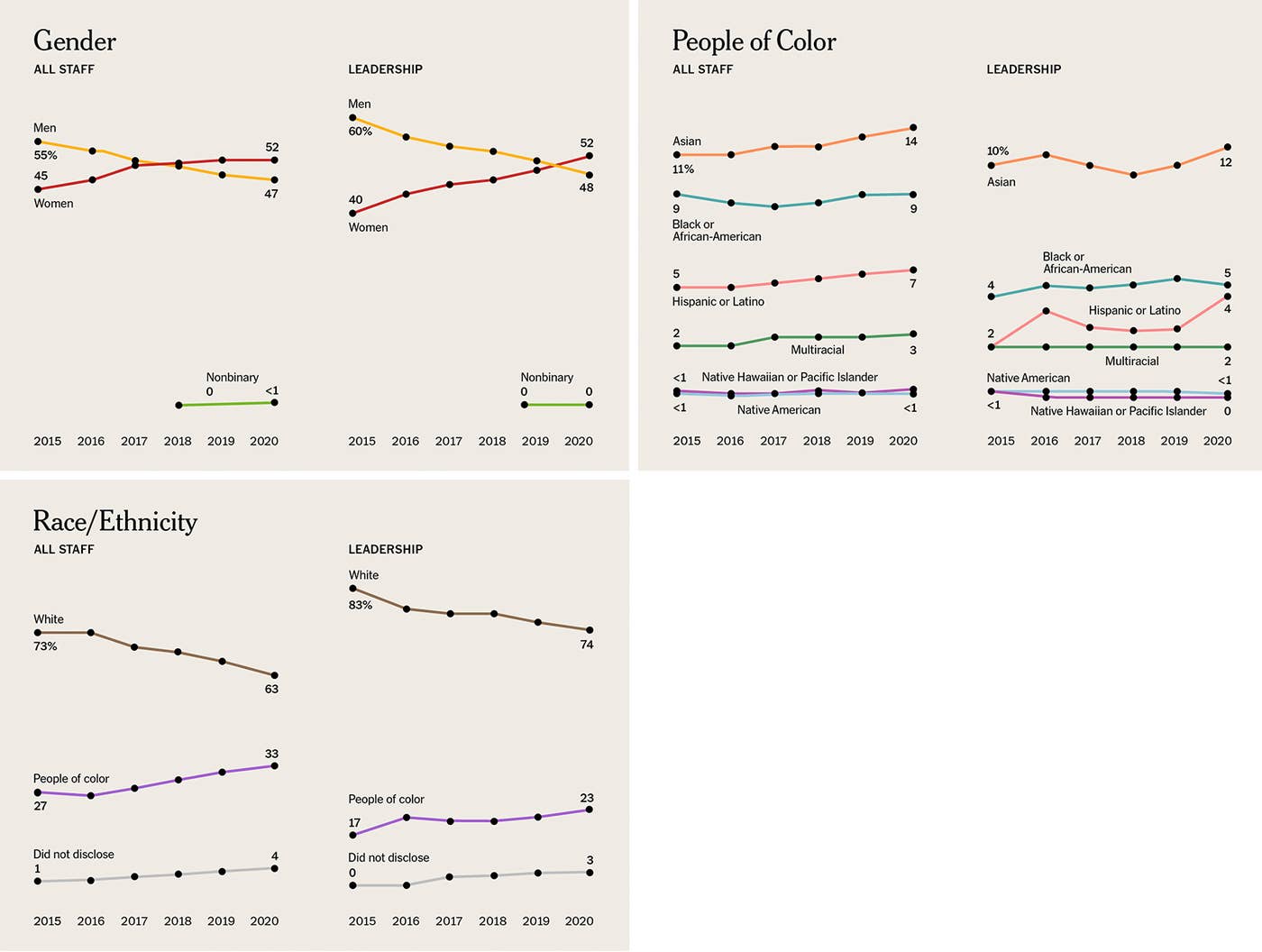

Last year, 48 percent of new hires were people of color. Since 2015, we have increased the overall percentage of people of color at the company from 27 percent to 34 percent; and we have increased the percentage of people of color in leadership from 17 percent to 23 percent. We have also increased the percentage of women at the company from 45 percent to 52 percent; and we have increased the percentage of women in company leadership from 40 percent to 52 percent.

The authors stress that hiring isn’t the end of the story and that good intentions aren’t enough. “Because we’re making a difference in society and have a mission, we feel like we’re already equitable and inclusive,” one staffer told them. “Because we care, we don’t have to work as hard. But that’s wrong.”

Elevate how we lead and manage people. We will define clear expectations for leaders who manage people and for how they will be assessed. We will significantly increase the feedback, training and support we provide managers. We will set a goal of increasing the representation of Black and Latino colleagues in leadership by 50 percent by 2025.

Leadership here is defined as director and above on the business side and deputy and above in the newsroom, which equates to roughly the most senior 10 percent of the company.

Here’s that element that was entirely missing from the 2014 Innovation report:

We will make our newsroom more diverse, our editorial practices more inclusive, and our news report one that provides a truer, richer and more textured portrayal of the world. By doing so, we will ultimately attract a reader and subscriber base that more fully reflects the breadth of the society we serve.

The authors outline a number of “cultural inhibitors” that “stand in the way of us becoming a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive company”:

— Success and belonging at The Times are guided by a set of complex, unwritten rules.

— A narrow view of excellence limits our ability to benefit from difference. “That’s not Timesean” can be used to exclude.

— We have discomfort with vulnerability, which is a barrier to taking risks, innovating, acknowledging mistakes and working on self-improvement.

— We often focus on how smart one person is, versus how smart that individual makes the team.

— Some people make the flawed assumption that there is a tradeoff between diversity and excellence.

Ideas that may have felt “implicit” to some people must be made explicit:

— Explicitly tie diversity, equity and inclusion to our stated values. We will ensure that principles on diversity, equity and inclusion are reflected in our stated values.

Set clear expectations for norms and behaviors for all employees. A team of news and business leaders, with input from a range of employees, will define the behaviors that lead to success at The Times — and those that don’t.

There are no names named in this public report, but the authors suggest that the Times has focused too much on individual stars (“people who make outsize individual contributions”) and while not rewarding the practices of “successfully leading people or contributing to teams. This fact can be detrimental to everyone in the organization, but we know it takes a disproportionate toll on people of color.”

Managers need to be effective leaders; the definition of “effective” includes the ability to “successfully lead diverse teams.”

To ensure that managers develop as people leaders and both benefit from and are evaluated based on the experience of those who report to them, we will build a feedback process that gives employees the opportunity to provide upward feedback for their managers. We will also provide new learning and development opportunities to support the growth and development of leaders as we set new expectations. And we will ensure that promotion rationales and compensation decisions for managers consider leadership abilities, making explicit in policy and practice that poor leadership of our employees will hold them back from advancing through the organization.

All employees will be able to give upward feedback for their managers, who will be assessed directly on their performance as managers in their evaluations. Starting in 2022, we will ensure that clearly defined diversity, equity and inclusion expectations are woven into all leaders’ assessment and compensation.

In addition, the report says the Times must work to ensure that “stars” aren’t treated differently from other staffers. (The “recent events” mentioned likely refer to the resignations of Donald McNeil Jr. and Andy Mills; I am guessing that Michael Barbaro and Rukmini Callimachi‘s names also arose in conversation with staffers.)

Amid recent events, employees have pointed to a “star” culture. They have questioned The Times’s commitment to fairly enforcing its policies and rules — and whether they are clear and rigorous enough in the first place.

The Times’s leaders have committed to a review, now underway, of our procedures for investigating employee behavioral issues, and for determining the appropriate discipline. The goal of this work is to clarify for all employees what our procedures are, to assess whether they are rigorous enough and to determine how to make them more transparent. The result must leave colleagues with confidence that standards are applied consistently, that processes are rigorous and fair, and that action is taken when violations are found to have occurred.

Times employees, especially employees of color, are often unsure of how to advance at the organization and unfamiliar with how promotion decisions are made, the authors write. “All employees deserve to know where they should aim, to have opportunities to put their hands up, and to have a fair shot at advancement and opportunities to grow in their existing roles.” The newsroom will need to take a cue from the Product Development teams:

There, career paths are well defined and promotions for those who are ready to rise in the organization are granted in specific windows each year. Managers and employees know when and how to propose promotions, and at the end of the process, employees receive clear decisions and feedback. While these processes are by no means perfect, they have the power to bring considerable rigor and fairness to personnel decisions.

The newsroom has begun to develop its own set of clear, fair career development processes. We need to ensure that people of color share in the opportunity for stretch assignments that can lead to more senior roles or growth in employees’ existing positions. And senior leaders should be judged by how well they create pathways for a diverse group of deputies to succeed them.

When the Times doesn’t create dedicated positions focused on diversity, equity, and inclusion, the work needed in those areas goes unpaid and falls to employees of color, the authors note.

Our lack of clear ownership and uneven systems has meant that people of color have shouldered a disproportionate share of this responsibility, often on their own time and without additional compensation. They lead employee resource groups (E.R.G.s), like Black@NYT, the Latino Network, the Asian Network, the Arab Collective and others. They serve on diversity committees (including this one) and participate in focus groups and listening tours. And they often read and edit articles concerning race to ensure accuracy and fairness in between their other duties. All of this work has been essential and has illustrated the commitment of so many people of color at The Times to the institution and to improving our workplace culture.

The Times has already taken some steps to bolster our companywide approach to diversity, equity and inclusion. We recently announced, for example, that E.R.G. leaders and committee members will receive annual stipends to recognize the work they do.

More broadly, we will build out an office within Human Resources to add expertise and oversee our efforts at making the company more diverse, equitable and inclusive.

“Sensitivity reads” should be made obsolete, the report’s authors write; they’re a symptom of “coverage that remains rooted in white perspective, from characterizations and discussions of race to notions of what’s newsworthy.” Employees of color should not be brought in at the last minute to ensure that “story framing and language hold up to our news standards and do not play into tired stereotypes.”

And while the term “objectivity” doesn’t appear in this report, this passage is noteworthy.

As we continue to diversify our newsroom, we will see more coverage that captures the lives of people and communities of color with deeper understanding and nuance. After all, while our journalists rely primarily on reporting and expertise in the subjects they cover, personal experience can also deepen and enhance their work.