In a paper summarizing 30 years of sports coverage on televised news and highlights shows, researchers began by quoting a short segment dedicated to a WNBA game between the L.A. Sparks and the Atlanta Dream.

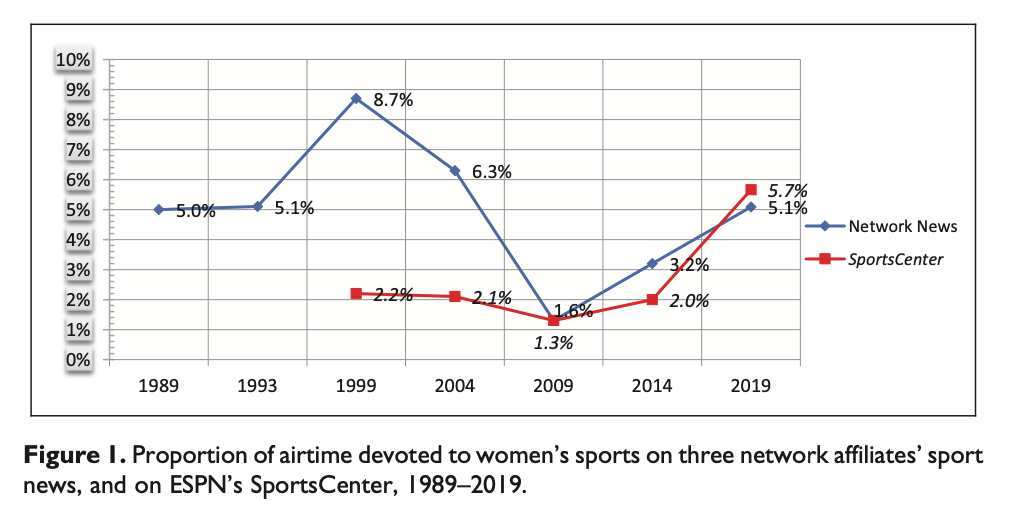

The broadcast was unusual, authors Cheryl Cooky, LaToya D. Council, Maria A. Mears, and Michael A. Messner pointed out, in that women’s sports were mentioned at all. They found that 80% of the televised sports news and highlights shows included zero stories on women’s sports. The overall portion of sports coverage featuring women had been low for decades and, in 2019, an overwhelming 95% of the sports coverage included in their study focused on men’s sports.

But, they wrote, the WNBA segment was typical in other ways. The 23-second-long clip was the only mention of women’s sports in the six-minute long sports segment — and it was also the shortest. Other coverage included Major League Baseball games and the men’s Wimbledon final, but also segments on a celebrity golf tournament and a competitive hot-dog eating contest.

“In short, the WNBA story — the shortest in duration of the six in the broadcast — was eclipsed by five longer reports on men’s sports, stories ranging from in-season sports (MLB, pro tennis), an out-of-season sport (NBA), to human interest and comedic entertainment only tangentially connected to what most people think of as sports news,” the report found.

The study analyzed sports coverage on local network television (the Los Angeles affiliates KCBS, KNBC, and KABC) as well as highlight shows like ESPN’s SportsCenter over the 30 years.

In 2019 — after sport media producers and others suggested televised news and highlights shows were not as relevant as they once were — the researchers started to include online and social media sources, like Twitter accounts for the networks.

The proportion of coverage dedicated to women’s sports in email newsletters and Twitter was higher than TV news and SportsCenter, but only if the researchers included espnW and its online newsletter. ESPN stopped producing espnW’s weekly newsletter, however, and, when researchers removed the data from their sample, the proportions dedicated to women’s sports mirrored that found on TV news and highlights shows.

The researches said they expected that “without the time and space constraints faced by mainstream media outlets like television news and highlights shows,” social media accounts would devote more content to women’s sports. Instead, they found that 91.1% of posts were dedicated to men’s sports.

Here’s what else stood out from the study.

For televised sports shows, it’s “never too early” to cover the “big three” of men’s sports — basketball, baseball, and football — and there’s “never too much” coverage.

While the portion of coverage dedicated to women’s sports on TV news and highlights shows has consistently remained “dismally low”, “viewers of these shows are fed a steady diet of men’s sports, especially the Big Three of football, basketball and baseball.”

This held true, even when the sports were out-of-season and the coverage dwelled on questions like “Who will be the starting pitcher for the L.A. Dodgers on opening day?” weeks before the MLB team was scheduled to take the field.

Researchers called the tendency to promote men’s “Big Three” sports during the off-seasons “not anecdotal” but “systematic.”

“As much as anything in our study, this tendency to promote men’s Big Three sports during their off-seasons while rarely if ever mentioning women’s sports during their off-seasons reveals how mainstream sports media works to actively build and maintain audience knowledge, interest, and excitement for these men’s sports,” they wrote.

The researchers described coverage of women’s sports in the 1990s that “routinely trivialized, insulted and sexualized women athletes.”

“This 1990s frame foregrounded conventionally sexy, model-beautiful (and mostly white and blonde) women athletes like [tennis player Anna] Kournikova, while rendering invisible other women athletes—even those of greater talent and accomplishment—who did not conform to that narrow image of culturally-valued white femininity,” researchers found. By 2014, however, that frame had been replaced with “an attempt at a more ‘respectful’ framing of women’s sports that was delivered in a ‘boring, inflection-free manner.'”

One of the study’s authors described the resulting coverage as begrudging and perfunctory.

“Our analysis shows men’s sports are the appetizer, the main course and the dessert, and if there’s any mention of women’s sports it comes across as begrudging ‘eat your vegetables’ without the kind of bells and whistles and excitement with which they describe men’s sports and athletes,” Messner said.

The researchers call the style “gender-bland sexism”:

In contrast, viewers of stories about men’s sports were constantly immersed in a sea of colorful and dominant verbal descriptors, delivered in excited and widely-modulated voice intonations, such as, “emphatic dunk!,” “lethal,” “on fire!,” “in command!,” “exclamation point!,” “Boom!,” “a force,” “crushing!,” “Unstoppable!,” “throwin’ heat,” “monster jam!,” “took control!,” “ripped up!,” “ferocious dunk!,” “high octane!”.

Commentators were adept at amping up the enthusiasm in their men’s sports stories with statements such as the one SportsCenter’s John Buccigross deployed in describing then-college basketball phenom Zion Williamson: “He’s such an unpredictable bundle of energy that it reminds one of watching a swelling storm on Doppler radar.” Women athletes were rarely, if ever, described in this way.

The charitable contributions of male athletes found coverage on news and highlights shows, but similar contributions by female athletes, including their social justice activism and charity events, almost never made the news. “These omissions help paint women athletes with a more one-dimensional, gender-bland brush,” the report found.

The researchers found March Madness — the NCAA basketball tournament — useful for comparing news and highlights coverage between men and women. (You might have seen that players recently found that the difference in facilities provided to men’s and women’s teams instructive, too.)

“Unlike many sports, where there are major structural asymmetries that at least partly explain differences in reportage — for example, the existence of no women’s equivalent to men’s college football, the NFL, Major League Baseball (MLB), the National Hockey League (NHL), or the fact that the WNBA has a far shorter season than the NBA, and is scheduled during a different time of the year (summer) — the women’s and men’s NCAA tournaments are equivalent events, played during roughly the same several weeks,” they wrote. “As such, they provide a source ripe for comparison.”

The report found that “March Madness” is promoted as “mostly for men.” In 2019, local television shows devoted 1 hour and 14 min (56 stories) to the men’s tournament while spending just 3 min and 16 seconds (8 stories) on the women’s tournament. At ESPN’s SportsCenter, the show dedicated more than 2 hours and 13 minutes to the men’s tournament (27 stories) and only 3 min and 43 seconds (just two stories) to the women’s tournament.

The online newsletters mirrored the televised coverage with 48 articles on the men’s NCAA tournament and only six articles (four of them from espnW.com) on the women’s tournament.

The conventional, asymmetrical ways in which broadcasters talk about sports — coverage did not gender mark the NCAA tournament as the “Men’s NCAA tournament” or call participants “male athletes,” for example — positions men’s sports as the universal standard norm, the study noted.

A few stories in women’s sports broke through. There was a “celebratory and generally high-quality mini-spike of coverage of African American women tennis players” in the summer of 2019. (That year, 15-year-old Coco Gauff became the youngest qualifier in Wimbledon history and Serena Williams reached the final match.)

But no story broke through more than United States women’s soccer. The U.S. national team earned their record fourth title at the Women’s World Cup in July 2019 and they were responsible for an outsized amount of the women’s sports coverage in the report.

“Absent the [Women’s World Cup] stories, in other words, the overall 2019 women’s sports TV airtime drops from 5.4% to 3.5%,” the study found.

The soccer team was also responsible for all of the lead stories — which tend to be longer and of higher production quality than other stories — that featured women.

“Of the 251 broadcasts we analyzed in 2019, five (2% of the total) opened with a story on women’s sports: all five were in the month of July, and all focused on the U.S. Women’s National Team winning the World Cup,” the report noted. (In 2014, there were zero lead stories that focused on women’s sports.) After analyzing the coverage, the authors have a theory on why:

How might we explain why this single women’s sports story was elevated and spotlighted so dramatically, when nearly all other women’s sports stories struggle to be covered at all, much less with the same quality, duration, and excitement of men’s sports stories? A large part of the answer lies in understanding how nationalism infuses sport and sports media.

On a world stage, these events create a context in which nationalistic pride can be promoted and amplified, as the WWC coverage above illustrates, complete with American flags, clips of the national anthem being played, and commentary that celebrates “patriotism,” “red-white-and wow,” and “world domination night” by “our” team. For a moment, nationalistic pride trumps the sexist tendency in mainstream media to ignore women’s sports.

The researchers cautioned against using the U.S. Women’s National Team as a harbinger of more equitable sports coverage in the future.

A sobering benefit of having done this research for 30 years is that we know that there have been several such “watershed moments” in the past … The reality is, following bursts of nationalistic media coverage and flurries of public celebration following these high-profile U.S. women’s international championships, there has been little to no subsequent spillover into increased quantity or quality of mainstream media coverage of everyday women’s sports. Nationalism can sometimes trump sexism, or even gendered racism in media coverage of women’s sports, but it does so only for a moment, its impact transitory and short-lived.

The study was published in Communication & Sport. You can read more here.