What sorts of media diets actually make you more knowledgeable about politics?

Is it one packed full of newspaper fiber? High-sugar clickbait? A day full of smartphone snacking, or three square meals? Can cable news really be part of a complete breakfast? Er…any idea what keto news consumption would be in this over-extended metaphor? (Vice, maybe?)

A new study in The International Journal of Press/Politics, looking at news usage in 17 European countries, finds that good ol’ traditional media is probably best for your political IQ — including high-quality public media, if you can find it. A vigorous online news regimen can also be good for knowledge, mostly. But ironically, gorging on all the news you can find might leave you less informed than someone who’s more selective.

The list of researchers is a veritable Schengen area of academics — 18 in all, led here by Laia Castro of the University of Zurich.1 (They make up NEPOCS, the Network of European Political Communication Scholars.)2 Here’s the abstract, emphases mine.

The transition from low- to high-choice media environments has had far-reaching implications for citizens’ media use and its relationship with political knowledge. However, there is still a lack of comparative research on how citizens combine the usage of different media and how that is related to political knowledge.To fill this void, we use a unique cross-national survey about the online and offline media use habits of more than 28,000 individuals in 17 European countries. Our aim is to (i) profile different types of news consumers and (ii) understand how each user profile is linked to political knowledge acquisition.

Our results show that five user profiles — news minimalists, social media news users, traditionalists, online news seekers, and hyper news consumers — can be identified, although the prevalence of these profiles varies across countries. Findings further show that both traditional and online-based news diets are correlated with higher political knowledge. However, online-based news use is more widespread in Southern Europe, where it is associated with lower levels of political knowledge than in Northern Europe.

By focusing on news audiences, this study provides a comprehensive and fine-grained analysis of how contemporary European political information environments perform and contribute to an informed citizenry.

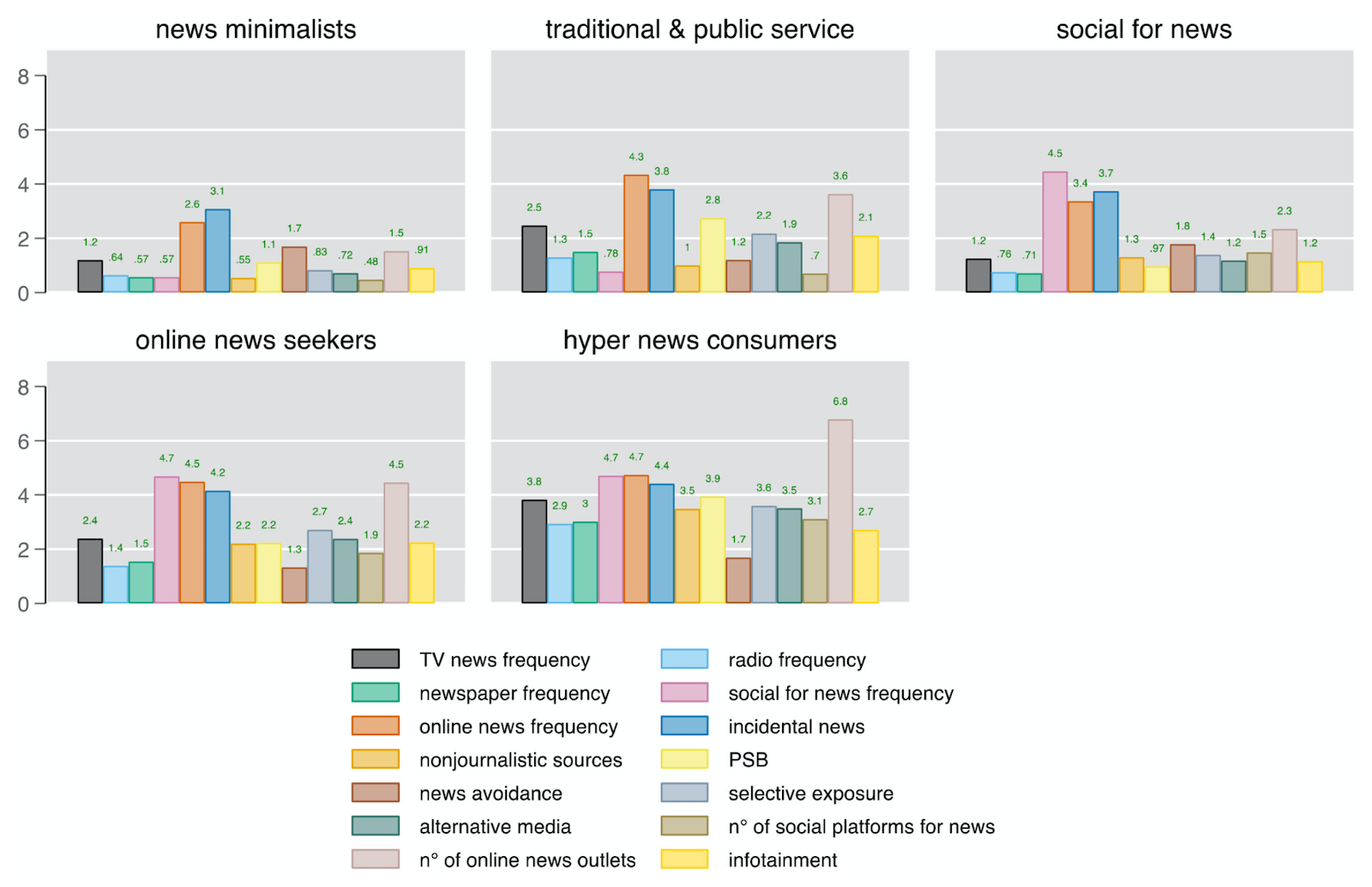

The research is based on an online survey of 28,317 Europeans, with per-country samples of around 1,700 each. (The samples are “fairly representative” of the broader populations, though a little more female, a little more educated, and a little younger.) Subjects were asked about how frequently they used different kinds of news media — TV, radio, newspaper, public service broadcasters, social media, online news sites, alternative media, and “infotainment” (political talk shows, comedy news shows, etc.). Researchers also asked about how often they actively try to avoid the news, how often their friends share news stories on social platforms, and how often they bump into political news without specifically seeking it.

They used the responses to all of those questions to categorize people into five “news user profiles”: news minimalists, social media news users, traditionalists, online news seekers, and hyper news consumers.

Here’s a visual of those findings in pastel chart form:

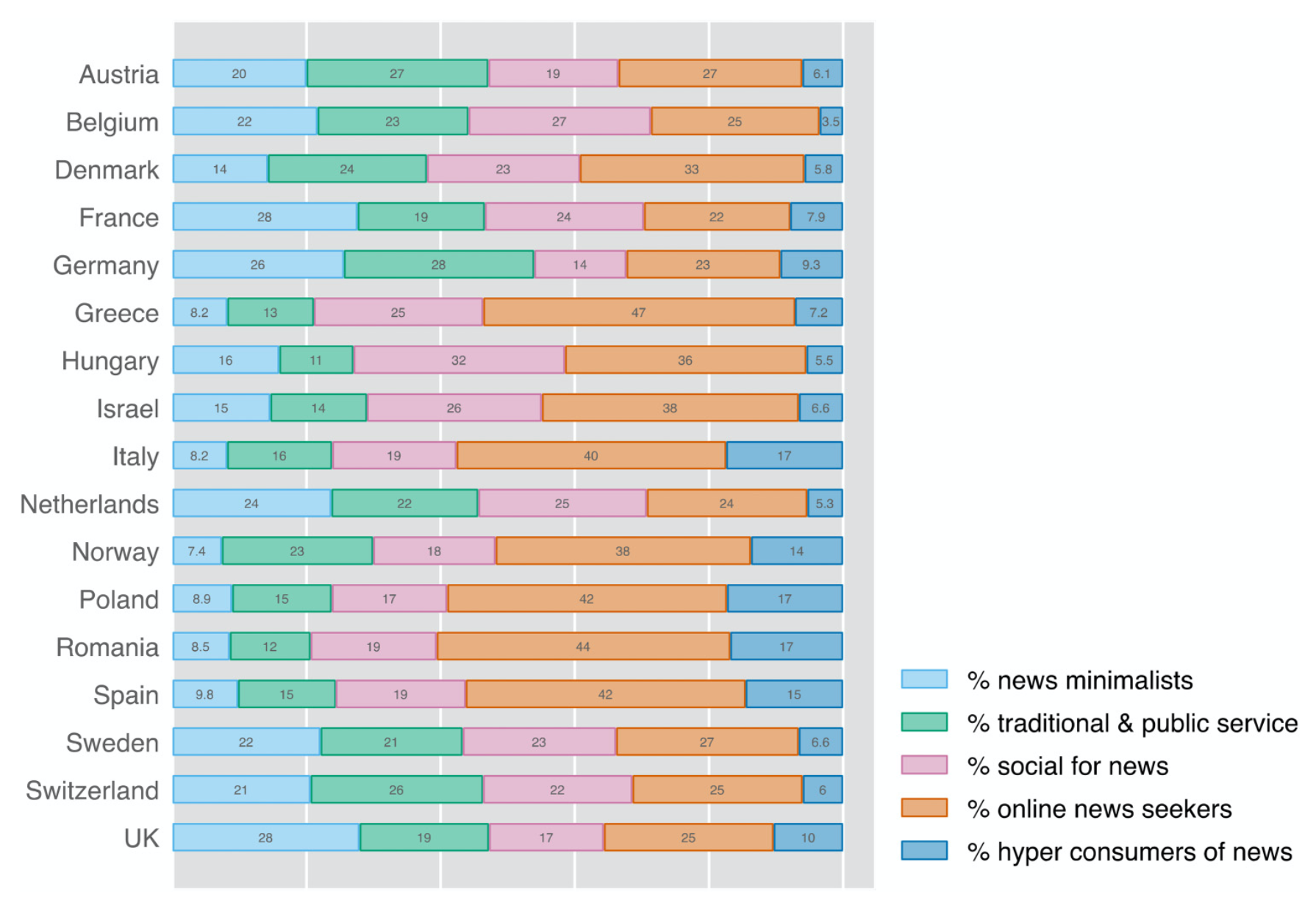

The researchers also looked for variations between countries. Northern Europe’s biggest economies — Germany, France, the U.K., the Netherlands — tend to have high shares of “news minimalists.” (The researchers connect this to those countries’ higher levels of international integration: “News minimalists are most prevalent in globalized, heterogeneous societies that exhibit a high movement of people through labor mobility, migration, and cosmopolitanism.”) But in much of southern Europe (Spain, Italy, Greece), minimalists are, well, minimal.

Meanwhile, people in those southern countries are substantially more likely to be online news seekers or hyper news consumers than their richer neighbors to the north. (Why? Online media is cheaper, and their established media outlets are less trusted.) The richest countries also tend to have a higher reliance on public broadcasters, which are typically funded at a higher level than elsewhere.

That’s all interesting — but what sort of news diet actually leads people to know more about the political situation they’re living in?

Along with all those questions about consumption patterns, survey subjects were also asked a bank of multiple-choice political knowledge questions to see how well informed they are. (Some questions were the same for everyone, and others were country-specific.) Items included: Who is Greta Thunberg? Who is the new leader of the European Commission? Who is your country’s current minister of foreign affairs? What percentage of people living in your country were born outside of it?

The results?

…a key finding is that only two user profiles (traditionalists and online news seekers) are positively and consistently correlated with political knowledge compared to the rest of the user profiles…More specifically, the results show that those having a more selective and richer online news diet (online news seekers) are more likely to hold higher levels of surveillance knowledge compared to all groups of news users with the exception of those using traditional and public media, who are comparatively better informed than all the rest.

Strikingly enough, the hyper consumer of news profile shows either nonsignificant associations with political knowledge or (when compared with traditional and online news seekers) even negative correlations. We anticipate the most plausible explanation thereof stems from information overloads, as we more extensively discuss in the final section of the paper.

So: People who rely heavily on traditional and public media correctly answer more factual questions about politics than everyone else. People who seek out a lot of news online also fare above average. Those are the third and fourth groups listed above, one leaning female, the other leaning male.

(Interestingly, for online news seekers, the associated increase in political knowledge was found in the Scandinavian countries — but not in southern ones, and not even in the big northern economies like Germany, France, and the U.K. The positive knowledge effect for traditional/public media users was found more consistently across countries — but still not in Italy, Greece, or Poland.)

It shouldn’t be surprising that people who only consume a minimal amount of political news don’t know a lot about political news. And neither do all the Facebook scrollers who think the news will find them.

(From the study: “This is in line with findings…that people do not learn much from following the news on social media. This suggests that the potential positive effects of incidental exposure to news information through social networks might be offset by, for example, exposure to a sizable proportion of user-generated content and unreliable information conveyed through personalized streams and like-minded others.”)

But the hyper news consumer — let’s call him or her Dr. Twitter List von RSS Reader, Esq. — doesn’t see a return on all that time invested in terms of higher levels of knowledge.3

That was kind of shocking to me, to be honest. What good are all these 283 morning newsletters in my inbox if they don’t make me smarter?

Indeed, our findings suggest that it is more about quality than quantity, since traditionalists consume information from a lower number of sources than most news profiles identified in this study. Accordingly, consuming news from a broader range of news outlets, channels, programs, and platforms does not necessarily make for a more informed citizenry, and it may even lead to the opposite.As our analyses show, respondents embedded in the hyper news consumers profile are less politically knowledgeable than the average news user. In line with previous research, this may be due to information overloads and a tendency for news snacking over actual news reading.

The avalanche of information and constant stream of news stories people are currently exposed to (not least on social media) makes it plausible that individuals using a multitude of sources find it ever harder to retrieve and process information from their available media. Indeed, compared to the other news profiles, hyper consumers of news use a greater number of online news outlets and social platforms for news.

The idea that information overload makes you dumber makes a certain sense, I suppose, but until I read this paper, I would have guessed that was a relatively rare outcome. But this is a systemic, statistically significant finding across more than 28,000 survey subjects and 17 countries. If you’re an information hypervore, that should give you a little pause.

Okay, pause over, back to Twitter.