Monday’s Worldwide Developer Conference felt unusually overstuffed. Without a marquee new laptop to announce or a big new chip strategy to discuss, it seems that Apple just packed a ton of updates into the operating systems that are always the stars of WWDC, iOS and macOS. They’re important to journalists because — especially in the U.S. and much of Europe — news organizations’ best customers disproportionately use iPhones, iPads, and Macs.

This year, Apple announced two big changes that could well make life more difficult for publishers, along with quite a few welcome features, reasonable tweaks, and interesting side experiments. All in all, while the news business was nowhere near center stage Monday, I think this will end up being one of the more impactful Apple events in a while for publishers.

These are the highlights; read straight through or skip ahead to whatever interests you.

Apple spent a lot of time pushing a new set of features around focus — about better separating the important stuff you want to focus on from the junk you don’t want to. The biggest, er, focus of that work is in push notifications.

If you’re anything like me, you get a gazillion push notifications on your phone a day. Not to get all Eisenhower Matrix on you, but some of those are important and urgent, some are important or urgent, and some are neither. But on your home screen, they’re all mixed together in reverse chronological order, and it’s easy for the dumb stuff to push the important stuff several screens down.

Apple’s tried to improve notification triage before; think of those “You don’t seem to be tapping on these DumbApp notifications; should I stop showing them to you?” notices you’ve probably seen. But it’s now going significantly further — and in a way that is risky for news outlets that rely on those push notifications for traffic.

These all sound appealing as a user — but they’re worrisome as a news publisher. How, exactly, will the “priority” level of an app be determined? There will be ways for users to manually adjust those settings, but the main work is done by Apple’s machine learning, based on how you interact with the apps on your device each day.

Will my iPhone’s algorithms decide that a breaking news story from Bloomberg is “urgent,” “important,” or “time-sensitive”? How about something more feature-y pushed by The Atlantic, or a game score notification from ESPN?

Maybe the algorithms will make only wise judgments — or maybe they’ll be like every other algorithm in the world and sometimes be a little off. As a commenter here noted, the example given on Apple’s site for the “top” message in a notification summary is…a very ad-like push from Yelp recommending a Thai restaurant.

Given that news apps send a healthy number of pushes per day — and that the value of those notifications often doesn’t require a tap to launch the app, which might make your phone think you’re not paying attention to them — I worry that these changes will make it harder for news to get noticed. At a minimum, it’ll be something for publisher tech teams to monitor, and likely to optimize for. Once you get away from straight reverse-chronological order, you’ve created SEO for push notifications.

It reminds me most of back in 2013, when Google introduced tabbed inboxes for Gmail — you know, the little sections that separate out your important emails from “Social,” “Promotions,” “Updates,” and “Forums” emails. As a user: helpful! But publishers know that having their newsletter or breaking news email buried in Promotions or Updates means it’s less likely to be opened. Gmail users can adjust the algorithm’s decisions — but most will always just stick with the default behavior. This change is worth watching.

Apple has spent the past few years leaning into its reputation for respecting user privacy, using its market position to influence how industries like ad tech operate. Just last month, it made every app that tracks your activities across other apps explicitly ask for your permission to do so. Turns out, people don’t want to be tracked, putting a big crimp in the ad models of Facebook and others.

The OS updates include a number of privacy and security features. Safari will now push you to the HTTPS version of a website if available. If someone steals your phone, you’ll now be able to track its location even after it’s been wiped clean. If some rogue app is using the microphone on your Mac to record you, a little notification will appear to let you know, as it does in iOS.

For paying iCloud customers, it’s offering something called Private Relay, which functions a bit like a VPN for web traffic, encrypting your data and splitting it into two intercept relays, allegedly making it impossible for your device to be connected to your web activity.1 And Hide My Email will make it easy to create (and later delete) burner emails that forward to your real one, building on last year’s Sign in with Apple. (Interesting that those last two are paid features; Apple’s previously opened its privacy features to all users to buff up its brand aura.)

But these updates also add a new battle to Apple’s war against the digital ad business. One of the few bright spots in the news business in recent years has been this little boomlet in newsletters — maybe you’ve heard about it? Newsletter advertising is hardly the data-hoarding beast a Facebook ad is, but it does rely heavily on one little tracker: the tiny tracking pixels embedded in many emails that tell the sender whether their email has been opened, and often by whom and how many times. (Those little images are fetched live from a server, and the URL the email uses to grab it can contain some limited information, like the email address it was sent to.)

These images are the only way newsletter senders know if their emails are actually being opened. And that open rate is an important part of how newsletter publishers sell ads — as well as how they judge the relative success or failure of the email.

Along comes something called Mail Privacy Protection, a new feature that “helps users prevent senders from knowing when they open an email, and masks their IP address so it can’t be linked to other online activity or used to determine their location.”

There are very legitimate concerns about some distant server being notified whenever you open their email. But on the other hand, it’s kind of the bedrock of the newsletter industry.

There have long been ways to block tracking pixels, but they were mostly only used by nerds like me; this is Apple Mail, the dominant platform for email in the U.S. and elsewhere. According to the most recent market-share numbers from Litmus, for May 2021, 93.5% of all email opens on mobile come in Apple Mail on iPhones or iPads. On desktop, Apple Mail on Mac is responsible for 58.4% of all email opens.

Those numbers are crazy high — much higher than Apple’s device market share because Apple users spend a lot more time receiving and reading email than users on Android, Windows, or Linux. Overall, 61.7% of all emails are opened in Apple Mail, on one device or another.2 So even a small change in how it handles email has a huge impact on the newsletter industry writ large.

Maybe Apple will bury Mail Privacy Protection in some settings menu two levels down or something, and people won’t find it! Nope — this is apparently the first thing you see when you open Mail on iOS 15.

iOS 15: First launch of Mail app. pic.twitter.com/W4ewu9XFCk

— Ryan Jones (@rjonesy) June 7, 2021

As with the cross-app tracking permissions Apple started requiring last month, this is a very in-your-face feature. I’m certain the overwhelming majority of people will tap “Protect Mail activity,” because of course they will. And if you somehow don’t see that screen, it’s turned on by default.

Privacy protection in Mail is a setting that’s pre-selected. Don’t really see anyone turning that off. pic.twitter.com/noOrzwIdJk

— (@alexcwilliams) June 7, 2021

This 85-second video from one of Apple’s WWDC developer sessions makes it clear: Open rates will now officially be useless. Mail Privacy Protection will fetch those tracking pixels not just anonymously, but also automatically — meaning that every email you send to an Apple Mail user will appear as if it’s been opened, whether or not it actually has been.

here’s a video from Apple explaining in-detail how their upcoming “Mail Privacy Protection” feature works

tl;dr – email open rates & tracking data will continue their descent into irrelevancy pic.twitter.com/bBjg6dvILw

— Dame.eth (@jacksondame) June 8, 2021

(There’s also some good detail on the importance of tracking pixels to newsletter publishers in this thread from ConvertKit’s Nathan Berry.)

Creators will have to choose between taking extreme list cleaning measures where healthy, engaged subscribers get removed because they aren’t clicking emails.

Or they won’t do any list cleaning which will likely lead to spam filtering for both engaged and unengaged subscribers. pic.twitter.com/iSKPaMgLAK

— Nathan Barry (@nathanbarry) June 8, 2021

Matt Taylor, a product manager at the Financial Times, calls Apple’s new policy “lazy” and says it hurts small publishers most:

…much like generally-sensible-in-theory provision like the GDPR, moves like this from Apple are going to most hurt the solo publishers with their Substack newsletters.

A major publisher will be hurt, sure. They’ll lose a lot of data on which they sold their newsletter sponsorships. They’ll be less able to confidently purge subscribers who haven’t opened their newsletter in months (what if they’re iPhone users?)…

A smaller publisher, a local newspaper, a solo freelancer, a small blog; all these will lose data on a significant part of their audience. A likely valuable part of their audience. And it may stifle or slow their growth or opportunities.

Where previously you could unsubscribe readers who hadn’t opened your newsletter to save money, now you don’t know if they’re loyal or not. You’ll have to find other ways to entice them to let you know they are reading. A larger publisher can afford to keep 20,000 recipients on a list that never open an email. A smaller outfit cannot…

Apple’s fight for privacy is really a fight against the web. In signing up for a newsletter, a publisher or marketer already has a more valuable piece of PII: your email address. By focusing on IP addresses, and blocking trackers rather than proxying them on a fuzzy delay (which would provide the same useful publisher data without any PII leak of location or time), Apple are not really fighting for their users so much as they are fighting against email.

I’m sure newsletter publishers will adjust, somehow. If open rates are gone, they’re gone — you’ll have to find some other way to convince advertisers you have an attentive audience, and some other way to see how your email performed and keep your list clean. (Clickthrough rates live on, at least for now. Should we expect stripping URL parameters to be a feature in iOS 17?) But this is another sign that Apple’s war against targeted advertising isn’t just about screwing Facebook — they’re also coming for your Substack.

I don’t expect either of these to be earth-shatteringly important, but Apple showed two interesting new tools for sharing news.

In Apple News, macOS and iOS will now have a tab called Shared With You. (There’ll be similar tabs in Music and Photos.) If someone texts you a link to a Washington Post story, the Messages app should notice that and ship it off to that Shared With You tab — so it’ll be there for you to see the next time you’re checking out the News app.

How much people will use this is unclear to me; Apple News has a ton of users, but most of them fall on the relatively casual end of the news consumption spectrum, and I don’t know how many will find these time-shifted stories useful. One other question I don’t know the answer to: Will Shared With You will bring in any news article someone texts you, or only articles that already live inside Apple News? I’d assume the former, but that would mean, for example, articles from The New York Times (which isn’t in Apple News) would just not show up where users expect them to.

The second sharing feature isn’t even designed for news: SharePlay will make it easier for multiple people to consume the same content — like watch the same video or listen to the same songs — simultaneously during a FaceTime call. The most obvious use case here is for watching a movie or a baseball game with a friend who lives a few states away — while being able to chat as if you’re sitting next to each other on the couch. But I did notice that a number of streaming platforms that include news video to varying degrees — Hulu (which simulcasts ABC News), Paramount+ (CBS News), ESPN+, Pluto TV — are on board for SharePlay.

I wouldn’t expect many people to actually use SharePlay for news, but this is an interesting concept for watching it together. On Election Night, you and your politics-junkie friends could all get on a call and watch the returns coming in together. Or Oscars night, or the NFL Draft, or a presidential debate. Or, more depressingly, a hurricane hitting your hometown, or a terror attack, or a mass shooting. News recommendations get shared on social a bazillion times a minute, but news consumption is a pretty solitary experience on digital — more solitary, even, than the old network newscasts the whole family might sit in the living room for. Nice to see some efforts to bridge that gap.

A lot of journalists spend most of their days staring at an Apple-made screen, whether a Mac, iPad, or iPhone, and there are a few updates here that will be welcome for getting your work done.

iOS Safari can now install desktop Safari extensions — and those extensions can now include a ton of Chrome and Firefox extensions that Safari has lacked. And Safari’s new Tab Groups seem like a surprisingly decent solution to tab triage and organizing. (It looks better to me than Chrome’s clunky tab groups or Edge’s Collections, but of course no one’s actually used it yet.)

If you juggle devices all day, Universal Control — which lets you use the same keyboard and mouse/trackpad across up to three Macs and iPads at the same time — is a little mind-blowing, letting you treat multiple devices as three different screens for the same device.

Macs can now use Shortcuts, the iOS platform for scripting a series of actions across multiple apps; it could let you reduce some multi-step workflows to one click. (It’s more user-friendly in my experience than the old Automator app.)

Quick Note makes it easier to jot down a quick note on your iPad or Mac. Most interesting to me is that if you take a Quick Note while, say, you’re looking at a webpage in Safari, apparently the next time you visit that site again, the note should pop up and be accessible. Notes also has some tagging features that might make it full-featured enough for some to use it as their main scrap-text app.

If you use an iPad for work, multitasking looks a little better, but still nowhere near as intuitive as tapping command-tab to switch apps. There are still a lot of hurdles in the way of bringing the iPad to laptop quality for the sort of writing/editing/researching tasks reporters do all day.

Finally — and perhaps most importantly, at least at certain moments! — Macs will now have a Low Power Mode that’ll let you extend your battery. So if you’re tight on deadline and watching your battery tick down to 0%, Low Power Mode might just save the day.

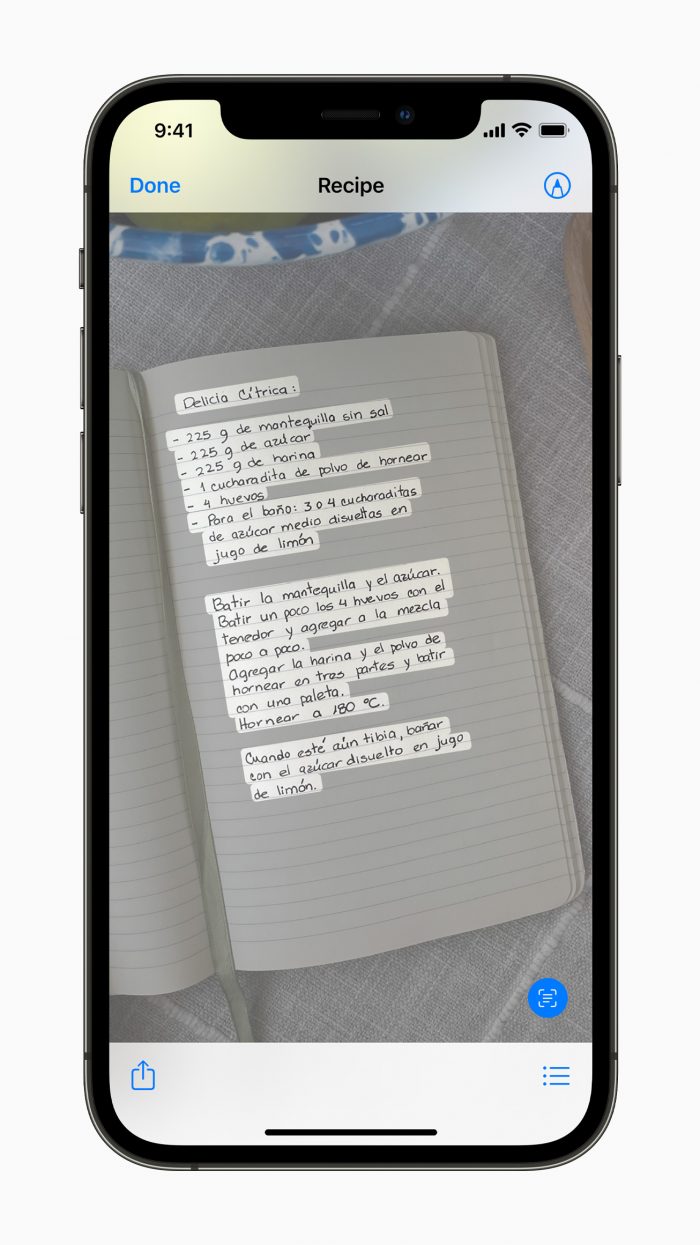

Four years ago, Apple introduced Vision, a framework for developers that lets apps perform a number of camera-driven tasks, like detecting a face in a photo or scanning a barcode. Two years ago, it added VisionKit, which made it easy to scan an image for text. That led to a small little explosion for instant-OCR (optical character recognition) apps for both Mac and iOS. Basically, OCR used to be a resource-intensive and complicated process to add to an app. It isn’t anymore.

I have to say: Easy instant OCR has been one of the most transformative recent features on the Mac for me. I use a little $7 app called TextSniper that lets me, with one keystroke, copy all of the text on a particular part of my screen to the clipboard — even if it’s just a picture of text, not text itself. (There are other apps that do the same thing, but TextSniper’s been the more accurate and reliable one for me.)

This is amazing for things like an old scanned PDF or print newspaper article: If it’s on your screen, you can copy it into a text document — which makes it searchable in all the usual ways. If you take nothing else away from this article, go try out TextSniper or a similar app and be amazed how many times a day you were retyping some chunk of text you couldn’t just copy.

Anyway, in the new macOS and iOS, Apple’s put that OCR ability and essentially made it automatic and systemwide. Have you ever taken a screenshot of some text? Your device will now automatically scan every screenshot you take (and every photo you take — every image on the device, basically) for text and make it searchable. (On Macs, this is apparently limited to devices with Apple Silicon.)

Maybe you need to be a digital hoarder like me to find this extremely exciting. But for some historical research I’ve been doing, I now have thousands of image files that contain text that isn’t recognized as text. Scans of 150-year-old newspaper articles. Paragraphs from a Google Books preview. Handwritten notes on an old letter. Screenshot of video stills. As soon as all that text is searchable, finding needles in that haystack gets a lot easier. I’ll be very anxious to see how well it works.

One thing the pandemic taught is the value of a good webcam, and the Mac’s (despite 18 years of practice) have been mediocre for years. (Weird, given that Apple makes some pretty amazing cameras for its iPhones.) The new M1 iMac it released in April showed the first real webcam quality improvements in a long time, and now macOS Monterey promises software improvements.

Probably most important for people recording video on their MacBooks is Voice Isolation, which promises to remove background noise from the room you’re recording in. (Sorry, Krisp.) The flipside is Wide Spectrum sound, which might improve your b-roll. Newer Macs can also use Portrait Mode in videos, which might look nice in a straight-to-camera news video. All three features will also be in iOS 15 for iPhones and iPads.

Apple announced all these as improvements specific to FaceTime, its video chat platform, but it appears they’ll also be available to other apps — so your Zoom calls or Instagram videos should also be able to benefit too, without any updates from the developer.

You’ll also now be able to join FaceTime calls from non-Apple devices like Windows PCs and Android phones. But they can still only be started on an Apple device, so your newsroom will probably stick to Zoom.