When the big announcement came in January that the Covid vaccine would soon be available in my state of North Carolina, an army of citizens prepared by reading research, watching videos, downloading data, memorizing talking points.

These warriors would become crucial in the delivery of misinformation and memes about the Covid-19 vaccine at the grassroots level.

These people are my neighbors. Their battlefield is the Nextdoor social media platform. And they’re intent on keeping their zip code from getting vaccinated.

Welcome to Nextdoor, where people can find a neighborly place to spew misinformation and damn the soul of a non-believer to hell — and then ask for handyman and hairdresser recommendations.

I began an unintended path through the ugly guts of Nextdoor in January, when two neighbors and I were helping elderly residents navigate the excruciatingly complicated task of getting Covid vaccination appointments. Nextdoor is popular in our corner of suburbia, so we used the platform as our communications vehicle.

But what I learned is this: Nextdoor is overlooked as a player in misinformation, and to address “vaccine hesitancy” in America, you might want to start at the neighborhood level, where hesitancy has grown into militancy.

If you’re not familiar with Nextdoor, it’s a social media platform that the company says is a place for people to “receive trusted information, give and get help, and build real-world connections with those nearby — neighbors, local businesses, and public agencies.” Participants are told to use their real names when they sign up for the platform and are gate-checked by Nextdoor to ensure that they actually live in the neighborhood. (Users are asked to verify their address with a copy of their mobile phone bill, driver’s license, deed or rental agreement, utility bill, or a letter from a bank.)

According to Nextdoor — which Axios this week called “the next big social network” and one that “has generally managed to avoid harmful content like rampant misinformation” — its user base grew more than 60% in the early days of the pandemic. The company claims it’s now used by one of every three households in the U.S. and 276,000 communities in 11 countries. Nextdoor, which makes money through selling ads on what it calls “the only platform to create meaningful local customization at national scale,” is valued at $1.1 billion.

Nextdoor is an unusual social media platform in many ways, including the premise that what’s said in the neighborhood stays in the neighborhood. Because people outside a small geofenced area supposedly can’t access the platform, the conversation is supposed to be concentrated among a private, though sometimes quite large, group of neighbors.

Real-life experience on Nextdoor can be different for everyone, depending on the neighborhood, the day, and who’s dropped in to make a post or a comment. You’ll see lots of notices about lost dogs, Mexican restaurant recommendations, debates over car backfire vs. gunshot vs. fireworks, requests for insect identification.

Or you might see conspiracy theories straight out of Facebook, Reddit, Rumble, and Parler.

My county’s Covid infection rate has been relatively low compared to other counties in North Carolina. Early in the pandemic, Nextdoor reported a 58% increase in users in “dense suburbs” like mine. But my efforts to help people navigate the Covid vaccination process brought out the conspiracy believers, one by one, until the dialogue exploded into accusations of everything from child abuse to Satanism.

This was not what I bargained for when I set out to help people find the once-elusive Covid-19 vaccine appointments. I personally was determined to get on every waiting list in a five-county radius, but the process was complicated and time-consuming. To navigate it, I created a spreadsheet and an information document and then felt guilty about keeping this research to myself.

So we started our volunteer effort with a simple Google document, updated daily with tricks, tips, secret phone numbers — anything that might help people find their shots.

That turned out to be the first mistake. After posting a link to the document on Nextdoor, we had to shut off access to it — ruining our plans for a crowdsourcing effort — after someone began inserting comments and erasing text.

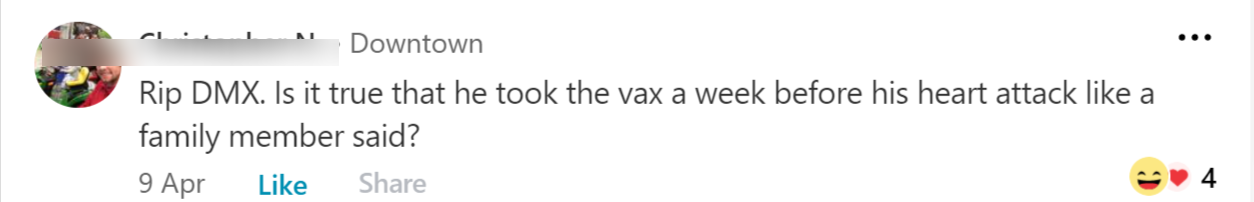

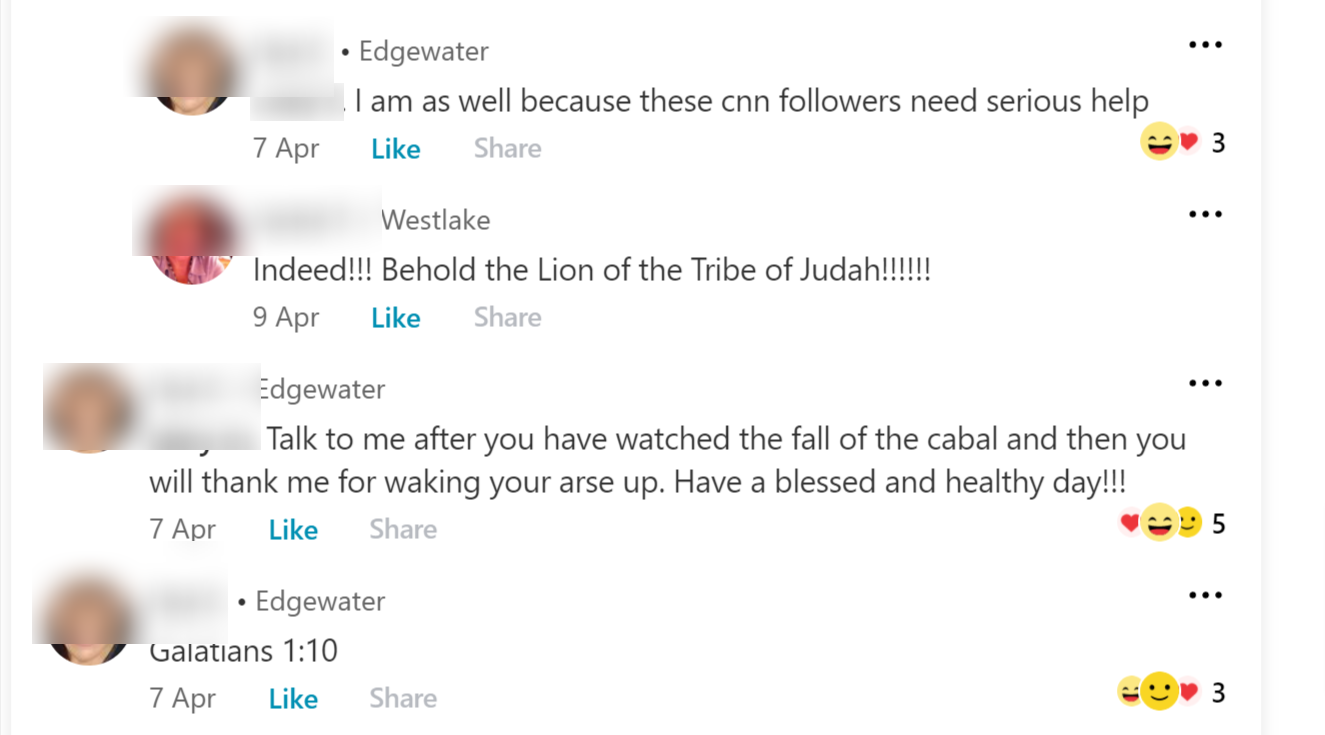

Then came the personal attacks, the QAnon memes, the persistent spammers. In the early days of our work, there was the occasional “No thanks!” or “Not for me!” comment when we posted information about a vaccine clinic. But the conspiracy conversation slowly emerged from wherever and however it was brewing. The anti-vaccine militants became bolder and more prolific, congratulating themselves and each other for speaking “the truth.”

Then came the personal attacks, the QAnon memes, the persistent spammers. In the early days of our work, there was the occasional “No thanks!” or “Not for me!” comment when we posted information about a vaccine clinic. But the conspiracy conversation slowly emerged from wherever and however it was brewing. The anti-vaccine militants became bolder and more prolific, congratulating themselves and each other for speaking “the truth.”

What really fanned the conspiracy flames were posts by our county health department — mundane public service announcements about new vaccine clinics and eligibility. More often than not, those posts led to an alarming conspiracy free-for-all.

In April, a county press release about vaccine eligibility for teens was followed by a 10-day dump of at least 1,336 comments — mostly lies, name-calling, accusations, and links to debunked vaccine “research.” Misinformation took over the conversation, with little objection but lots of heart emojis from conspiracy supporters.

Commenters admonished neighbors to “Do your research!” and posted dozens of links to viral misinformation sites, sometimes spamming the thread with nearly identical posts. Neighbors attacked other neighbors by name, posted memes pulled from conspiracy sites, called vaccinated people “sheeple” and warned of the End Times and the “mark of the beast”.

Commenters admonished neighbors to “Do your research!” and posted dozens of links to viral misinformation sites, sometimes spamming the thread with nearly identical posts. Neighbors attacked other neighbors by name, posted memes pulled from conspiracy sites, called vaccinated people “sheeple” and warned of the End Times and the “mark of the beast”.

A commenter who said he was 14 years old showed up to defend his parents’ choice to have him vaccinated. Other commenters berated him, or berated others for berating a child, or accused him of being an imposter. Threads like these typically devolved within minutes, sprinkled with homophobic and sexist comments and off-topic ramblings about Argentinian governance and carpetbagging.

All of this violates Nextdoor’s stated rules devised specifically for the pandemic: No false or misleading claims or conspiracy theories about the causes, cures, prevention, testing, safety and treatment of Covid-19; or anything “that could prevent or discourage people from receiving vaccines.” Some posts were removed after repeated complaints from users, but some remain as I write this.

Daniel Acosta-Ramos, an investigative researcher with First Draft, has studied misinformation on Nextdoor throughout the 2020 election and into the pandemic. The platform is just as full of “information disorders” as other social media platforms, he says, but Nextdoor manages to fly under the radar for two reasons: First, it’s hyperlocal and thus smaller in scale than Facebook and many other platforms. Second, it’s difficult for researchers and others to study Nextdoor, because users have access only to their own neighborhood posts.

Still, Nextdoor’s misinformation problem has been reported in communities around the country. Early in the pandemic, BuzzFeed News warned of Nextdoor users spreading misinformation about the coronavirus, including a post that said the virus was spread by Bradford pear trees. A year later, CNN reported that fake vaccination sites were posted on Nextdoor. Several Nextdoor users told Vox that their neighborhood group had been overrun by “a loud minority” spreading conspiracies.

Acosta-Ramos says it’s crucial to scrutinize misinformation on Nextdoor. “It can actually generate harm” because of the outsized influence neighbors can have on one another. Nextdoor users are required to use their own names, so someone who’s promoting conspiracies could sway the thinking of a neighbor who may be on the fence about, say, whether the Covid vaccine can make women infertile. (Nope.)

“They’ll say, ‘I know she goes to church every Sunday, shouldn’t I believe her?’” Acosta-Ramos says.

As a longtime journalist with an extensive background in the study of misinformation, I know that false information that’s repeated over and over can eventually be seen as truth by some people — particularly when no one responds to the misinformation with facts. The illusory truth effect plays out every day on the growing Nextdoor platform.

“It is problematic that users experience exposure to misinformation repeatedly,” says Acosta-Ramos. “That’s why you see some social media companies label problematic content, trying to counter that illusory truth effect.” Nextdoor, unlike Facebook and Twitter, does not flag content. Acosta-Ramos says Nextdoor also is known for being slow to respond to complaints.

If you’re wondering where Nextdoor moderation and oversight comes into play, I’m still wondering the same thing. Nextdoor has volunteer “leads” and “reviewers” who are supposed to “review and vote to remove reported content from neighbors, or close discussions that were started by neighbors,” says Dan Parham, head of public agency partnerships at Nextdoor. (Nextdoor leads have been criticized for making racist content decisions, and I’ve received private messages from leads who accused other leads of supporting conspiracy theories.)

The next level of moderation is Nextdoor’s “neighborhood operations team,” employees who handle users’ complaints about misinformation on the site, says Parham. “Given that this content can be particularly sensitive, we rely on our internal agents who have special training to ensure consistent and objective outcomes,” he said.

Nextdoor also has instituted a “Kindness Reminder,” which the company explains like this: “If a member replies to a neighbor’s post with a potentially offensive or hurtful comment, a Kindness Reminder will be prompted before the comment goes live.”

There’s a similar pop-up reminder for Covid-related posts. Of course, commenters can easily ignore the message and post away.

Some of my neighbors reported the Covid misinformation violations through the Nextdoor complaint process; this requires the user to click on three tiny, unlabeled dots on a post and answer a series of questions. I encountered many people who have no idea this function even exists.

Nextdoor says it addresses rule violations in several ways, from removing the content to permanently banning the neighbor from the site. But as Acosta-Ramos notes, banned conspiracists can resurrect themselves by using another email address.

Nextdoor CEO Sarah Friar told Axios the platform has “made a long-term decision that we’d rather not have the spikes on engagement from toxic-type content.” When no one responded to my neighbors’ complaints last month about the hundreds of problematic comments on a vaccine-related post, I finally reached Nextdoor through a DM on Twitter. While I quickly received a response that promised immediate action, the definitely unkind “engagement” continued for several more days. “Nextdoor is investigating the delay in addressing the comment reports, ” a Nextdoor spokeswoman told me for this article.

Meanwhile, some people in my Nextdoor Covid conversation haven’t taken a break from vitriol and conspiracies. But at least a few have been clearly disturbed by the conversation on a platform that purports to be a place for people “to receive trusted information, give and get help” and “encourage positivity.”

“Lordy mercy, people,” wrote one neighbor, “this breaks my heart.”

Jane Elizabeth, a media consultant, has been a manager and editor in several U.S. newsrooms including The (Raleigh) News & Observer, The Washington Post and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. She is the American Press Institute’s former director of accountability journalism and was a Knight Nieman Visiting fellow.