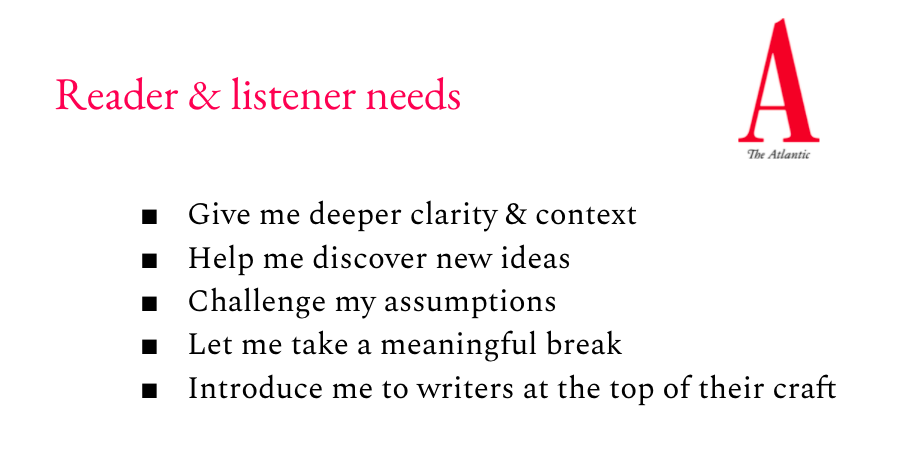

We’re committed to knowing what readers and listeners seek from The Atlantic, as well as learning where they are well-served by other media. We’ve gathered five research-backed, time-proven reasons that individual readers and listeners look to our journalism:

Here’s how we collected these needs: Our team at The Atlantic conducts survey- and interview-based research with current, prospective, and former subscribers, as well as with people in the U.S. and in other countries who listen to Atlantic podcasts and narrated articles. Among other topics, we ask research participants what makes our coverage unique, whether that means worth sharing, paying for, or vehemently disagreeing with.

The people we speak to and survey aren’t all fans of our work, nor do they all spend time with our journalism regularly. But the experiences of people who interact with us infrequently also expand our understanding of answers to the questions: Why do people seek out The Atlantic? What do they get out of the time they spend with us? We complement this intel, gathered over thousands of self-reports, with information that our data science, audience, and customer care teams gather.

Pursuing an understanding of what sets us apart is a highly useful, now routineized process for The Atlantic. We’ve been developing this list of reader needs since autumn 2019 and are continually validating and refining it. Just as the needs of our audience members change, this set of needs for our journalism will also adapt in the years to come.

What’s remarkable to me as a qualitative researcher who works within news organizations is how consistent these findings have been across reader and listener location, as well as over time: While it’s impossible to control for a global pandemic, answers to “why do you spend time with stories from The Atlantic?” have remained remarkably unchanged over the course of 27 months and two different U.S. presidential administrations.

I share these expressions because at The Atlantic we’ve found them useful for product design and development, as well as for some programming decisions by our audience team.

Associate editor Isabel Fattal said having the five needs on hand is generative for her work with Atlantic newsletters and our apps: “The reader needs help me stay intentional in how we’re using our readers’ time. On a practical level, the needs prompt variety in story selection — I use them, along with other editorial priorities and programming methods, to make sure we’re giving our audiences a balanced reading list.”

If you read our flagship newsletter The Daily, you’ll see that these needs have informed the composition of stories you see from us in your inbox each weekday. Senior associate editor Caroline Mimbs Nyce keeps the list below on her computer desktop and uses them as reference material for her Daily writing. She includes regular respite in the form of “A break from the news” in each dispatch.

These needs are not user stories or jobs to be done. Those are well worth developing, and I encourage your teams to pursue them, but unlike with personas, our intention isn’t to reduce people to core elements. We recognize that our readers and listeners have many interests, sometimes interests that compete for priority. Instead, we use needs statements to develop clear ideas and answers to the question: What UX motivations are we prioritizing with this experience?

We hear these five themes when we look to find out what needs our journalism meets, regardless of platform:

Give me deeper clarity and context. Across studies, we hear from readers and listeners that they come away from our articles, series, and shows feeling not just informed, but knowledgeable. They feel satisfied in being able to understand how systems work — and sometimes frustrated by learning how they break down.

Fattal said that in programming the Today feed in The Atlantic’s mobile app, this need statement has been especially useful to her. “After, or in the midst of, a monumental or shocking event, I’d try to think: What are my questions as an observer, and what questions is The Atlantic best poised to answer for our readers? I tried to make the most of The Atlantic’s ability to help readers contextualize what just happened, and to understand how we got to that point.”

Help me discover new ideas. We’ve become collectors of stories about how The Atlantic has turned people onto unexpected areas of interest, including natural world phenomena, the history of public education in the United States, and the inner workings of the British royal family. Print magazines offer the chance for immersiveness (the feeling of getting “sucked into” a story on a subject you knew little about) and adjacency (stumbling upon an unfamiliar topic).

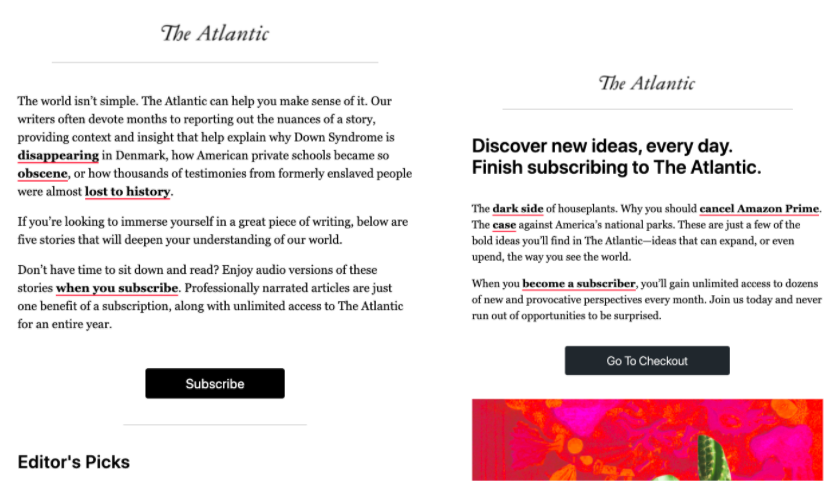

Our consumer strategy and growth team used this insight — that people who are familiar with The Atlantic appreciate the range that it offers — in planning recent marketing emails to prospective subscribers. (The sharp writing below is from senior copywriter Ashley Larkin, who also helped in synthesizing and clarifying the five needs statements.)

Challenge my assumptions. We continually heard that one of our strongest points of market differentiation is that we are provocative and don’t exist to represent a single perspective. We celebrate the heterodoxy and heterogeneity of our writers. From a political perspective, some people we’ve interviewed in brand research told us that The Atlantic is “absolutely a conservative” institution, while for other people it is“definitely a liberal” one. This tension is deliberate, and it is at the core of our editorial mission.

It says a good deal about our readers’ deep curiosity that they’re willing to spend time with fact-based arguments they may disagree with. Listeners to podcasts like The Review make time to hear from guests whose opinions don’t align with their own and whose ideas may not appeal to them. Given how easy it can be now to exclusively seek out media that supports one’s views, it’s useful to know that many of our readers do the opposite, seeking out a variety of perspectives … and sometimes change their own.

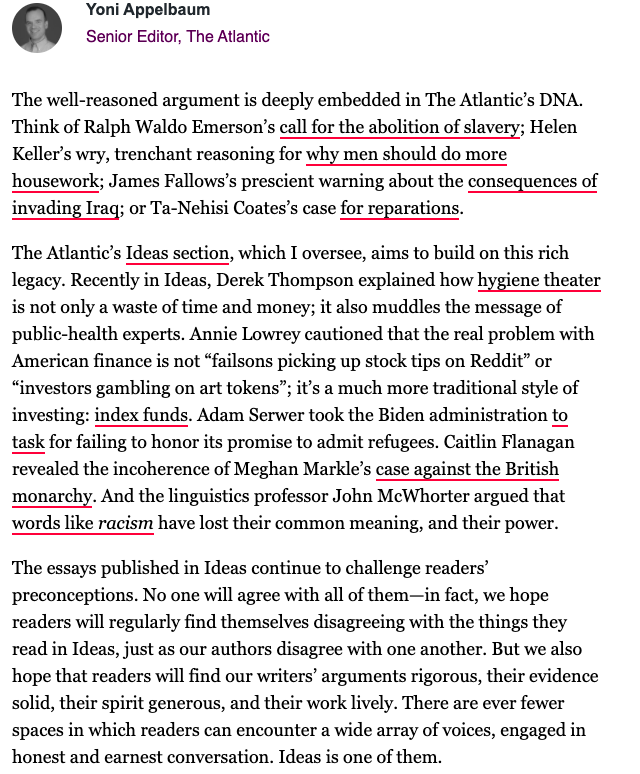

In another email to prospective subscribers, senior editor Yoni Appelbaum wrote about The Atlantic’s history of publishing well-reasoned arguments. He suggests that not even the longest-tenured subscriber agrees with everything we publish, and that’s a feature, not a bug.

Let me take a meaningful break. “I want to find a meaningful distraction,” one reader told us in a 2020 interview, echoing hundreds of thousands of others who sought a respite from seemingly endless doomscrolling. Amid unprecedented pandemic, political, and climate events, readers who “do the work” (in one subscriber’s words, describing people who dedicate time and attention to making sense of complex topics) needed a change. We heard that readers know where to go for schlock and “guilty habit” reads. When they come to us, they’re not looking to zone out. They’re looking for novel approaches into big picture topics.

We have substantial opportunities to direct readers to their subsequent reads on our site and app. We’re testing the placement and contents of our current Recommended Reading module and other recirculation mechanisms with these needs in mind.

On the product side, we think a good deal about appropriate moments to prompt a reader to pursue a different story or a different topic altogether. Our data science team has seen that “lighter” topics tend to appear earlier in a person’s path to becoming a subscriber and that “weightier” topics tend to be the reads immediately before a person makes a decision to subscribe. We don’t lean toward one of these over the other; rather, it’s the overall composition of topics a reader spends time with that matters most in driving return visits and subscriptions.

As an editor, Fattal said this need for a break has also been useful for counter-programming and planning purposes. “It’s just as valuable for our readers to have a way to decompress, to follow us down new paths of curiosity, and to have a reading experience that’s fun but not vacuous.” She continued, “Some of the best Atlantic articles are the ones that make you both laugh and cry, and that’s what I think a meaningful break can do for our readers.”

Similarly, senior editor Dan Fallon said that this need served the audience insights team as they were adjusting to a post-Trump, peak-vaccination-rollout moment in the spring of 2021. Culture, tech, science, and business stories began to attract a larger proportion of pageviews and subscription conversions than they had in the previous year. “We saw audience interests shifting, so we retooled several platforms to focus on more evergreen, culture, and science stories, and found some success doing that,” Fallon said. “Having the meaningful ‘break’ reader need on hand helped push us in that direction.”

Introduce me to writers at the top of their craft. Two related desires that emerged in 2021 research were: Introduce me to writers to watch and connect me with their ideas. One print and digital subscriber we interviewed said that she first came to The Atlantic through a politics staff writer she had geographic overlap with, but she renewed her subscription after developing an affinity for an Atlantic writer covering a very different cultural topic. She noted that the writing on display from both authors was different and deeper from what she found elsewhere on the web. This subscriber said the pairing contributes to her sense that The Atlantic is “credible, relevant, helpful, substantive.”

How we put it to use: Our editorial and product teams are considering this need when it comes to making it simple to follow individual writers and topics of interest. Email is a place where that need gets met for many readers and therefore a place for us to experiment. Building on the success of staff writer Robinson Meyer’s climate change newsletter The Weekly Planet, The Atlantic introduced nine writer-driven subscriber newsletters this fall and three new staff newsletters.

I will take off my researcher hat off for a moment to share that, as a reader, Nicole Chung’s new newsletter I Have Notes has achieved this need for me. I had heard about Chung’s writing and knew she was someone I shared interests with on topics as wide-ranging as adoption and developing a productive writing practice. Over the past month, becoming familiar with her reflections in newsletter form (including through a delightful reader advice column about creative professions) has led me to seek out her memoir.

Tori Sgarro, an Atlantic product designer who designed the user experience for the suite of subscriber newsletters (of which Chung’s is one), told me that the primary benefit of cataloguing these needs is shared organizational awareness: “The reader needs help most by giving everyone here a shared language to discuss Atlantic experiences from our readers’ perspectives.”

Know your audiences well enough to know their already-met needs. There is no alchemy here: These needs reflect only generosity from our research participants, and some time and diligence on our end. The five needs that readers and listeners meet with The Atlantic are unique to us, but we don’t have a lock on meeting them. Readers and listeners we reach don’t meet these needs exclusively with The Atlantic, nor would we want them to. We share audiences, and busy, resource-strapped people deserve to be well-served.

In this ongoing research, we hear two separate needs that people regularly go elsewhere to meet:

— “I want to know what’s happening right now”: Our readers and listeners spend significant time with other local, national, and international news sites for news of the day. When they come to us they often know what is happening and don’t need us to be a news aggregator.

— “I want to master the topics I care about”: Our audience members have wide-ranging passions, from community service to cycling to learning languages. A general interest publication like The Atlantic can’t offer the depth of knowledge they find in forums and through communities dedicated solely to their topical interests.

Hearing about these “met needs” is important and invites us to be disciplined about what our brand is.

I’m publishing this list because I want to encourage more media organizations to share what they find about what their audience members around the world need and want. Digital development editor Dmitry Shishkin did this at BBC World Service with good results. And while these needs aren’t the same as story aims, I suggest reading Vox editor in chief and former Atlantic managing editor Swati Sharma on six types of stories that make Vox coverage distinct.I hope you’ll use these lists as inspiration to talk to your own audience members and learn their met and unmet needs. Please publicize what you find: It makes all of our organizations more reader- and listener-inclined and curious.

Emily Goligoski is executive director of audience research at The Atlantic. A version of this story originally ran on Medium.